Rosetta's 10-billion-tonne comet

- Published

- comments

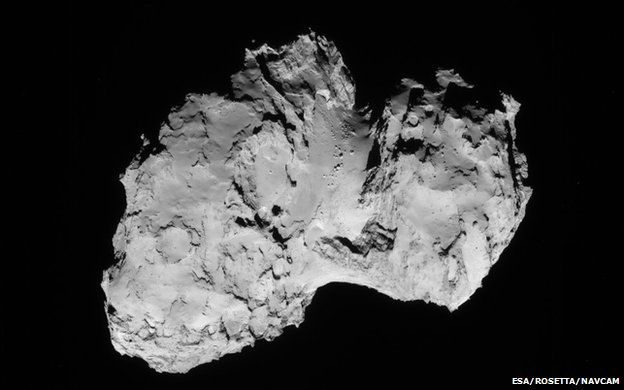

The comet being followed by Europe's Rosetta spacecraft has a mass of roughly 10 billion tonnes.

The number has been calculated by monitoring the gravitational tug the 4km-wide "ice mountain" exerts on the probe.

Ten billion tonnes sounds a lot, but it means Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko has quite a low bulk density, something in the region of 300kg per cubic metre.

If you could put the object in an ocean, it would float.

The calculation would seem to confirm suspicions that the comet is highly porous, and may even hide voids inside its body - but this is all to be determined.

"The mass is in the realms of what was expected," says European Space Agency (Esa) project scientist Matt Taylor.

"At this stage, it simply constrains what we believe it is made from, and as we get better measurements (closer up), there will be a lot of work to interpret whether the comet is heterogeneous or more 'bitty'. But not yet; this is the first measurement."

Rosetta arrived at 67P on 6 August after a 10-year chase through the Solar System.

It immediately began a complex fly-around manoeuvre, and it is from the way the comet's close proximity bent the satellite's path that scientists could gauge a mass.

Having such a number - which is equivalent to about 150,000 aircraft carriers, to continue the ocean analogy - is critical for mission planners as they design a safe orbit for Rosetta when it truly starts circling 67P in the coming weeks.

"Operationally, this can mean that planned orbits may be modified, as they assumed a different mass and hence gravity field," explains Taylor.

"Later, we will get more accurate information, in particular focusing on the centre of mass location, which will certainly come into play for landing site selection."

Rosetta is due to put down its contact robot Philae in November. A long list of five possible locations could be announced on Monday.

Sunday saw the probe drop another step in altitude, with pictures now being acquired from inside 80km.

Esa has been issuing daily images taken by Rosetta's navigation cameras.

Sadly, we have not had a new picture this week from the Osiris science cameras, which see much more detail.

The Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, who own the Osiris views, are keeping them under wraps for the moment.

Nonetheless, everyone you speak to continues to be enthralled by this object.

The surface features are so diverse - and go from the very sharp to the very smooth.

Some of the craters are truly intriguing. One, located on the comet's largest lobe, has tall, thin rims.

It resembles the crown-like splash-back you see when a liquid drop hits water in slow-motion.

But the form that is stirring perhaps the most debate is the streaks that are apparent in 67P's narrow "neck" region.

Are they a consequence of erosion, and possibly connected in some way to the boulders that clutter the neck terrain?

Or are they the result of some layering process, maybe when the body first formed and was accumulating material?

"Every time we get a picture back, it just blows me away," says Stephen Lowry, a Kent University researcher working on Osiris.

"We're going to be really busy trying to get our heads around all the features - to the point where the task is actually quite daunting."

Even scientists not formally connected with the mission are taken aback by what they are seeing.

Gareth Collins at Imperial College London is a specialist on impacts and cratering, and is "following the imagery with awe".

He is intrigued by what happens to the surface of 67P when it gets hit by another object in space.

Rosetta will establish precisely the nature of the materials that make up the comet and just how porous it might be.

Such properties will determine the styles of craters that can be sculpted, explains Collins.

"If the impactor is dense (rocky/metallic) then it likely produces a very deep, carrot-shaped cavity, largely by compacting pore space inside the comet, which then collapses to form a shallow depression on the surface.

"But if the impactor were to be another low-density comet or cometary fragment then it is possible the cratering process may be more similar to rock-on-rock impacts.

"Another factor is cohesion. At such low-surface gravities, even very small amounts of cohesive strength (think blancmange) can support towering cliff-faces."

This may help explain the crown-like rim of that fabulous crater.

One of the graphics we have used in the BBC coverage to try to convey the size of 67P shows a comparison with central London.

Which got me thinking: what would happen if 67P came down on the UK capital?

I should emphasise that this cannot happen because the comet does not come far enough into the inner Solar System to reach Earth, but let us unhook our imaginations for a moment.

Gareth Collins has an impact calculator that allows you to work out the kind of damage we could expect.

He has two versions, but the one I've been playing with allows you to vary more easily an impactor's parameters.

And for a 10-billion-tonne, 4km-wide, low-density object, travelling at some 50km per second - you can dig out an impressive bowl almost 40km across.

That is pretty much everything obliterated inside London's M25 orbital motorway system. Give it a go.

There's a serious side to this. Objects very similar to 67P, and bigger, have hit the Earth in the past; and they will likely do so again in the future.

What we learn from Rosetta and 67P may inform future generations on how best to deal with this threat.

- Published14 August 2014

- Published7 August 2014

- Published6 August 2014

- Published6 August 2014

- Published6 August 2014

- Published6 August 2014

- Published5 August 2014