Like space itself, the satellite-communications business can be a rather inhospitable environment.

Mobile networks Iridium and GlobalStar, the firms with the largest commercial satellite constellations, both spent time in bankruptcy proceedings before re-emerging as going concerns. Teledesic, a satellite-internet company backed by Microsoft, halted work in 2002, while SkyBridge, an Alcatel satellite internet project, went bankrupt in 2000.

So why is Elon Musk so eager to see his SpaceX commercial space transport company take a crack at a business that has been so troublesome?

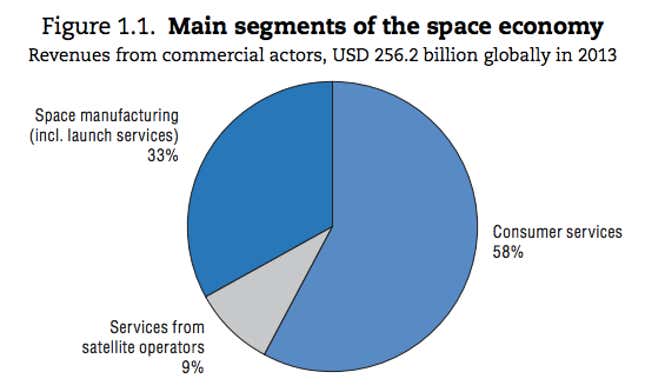

When it comes to profits in space, the biggest business is happening on the ground: You make money by building satellites and rockets, or by using satellites to beam information back and forth to earth. Orbit is just a place in your supply chain.

Most of the profits in the space business comes from satellite television. But like other tv broadcasters, this business is being eaten by the internet, forcing big companies to adapt to the new reality that all kinds of media are going to migrate to data networks.

Evolving business

“The whole satellite industry is reinventing itself,” says Susan Irwin, the head of satellite consulting firm Euroconsult’s US office. “The fact that television is going to be internet is changing the way that data, voice and video are distributed. There are advances in satellite communications that are making satellites more efficient, in value and bandwidth, and the use of satellites for internet traffic distribution is a business that is evolving.”

Existing satellite internet is expensive and dodgy, though—only 0.2% of internet users in OECD countries in 2012 used satellite broadband. Tests by US telecom regulators show it has 19 times the latency of terrestrial internet, thanks to the long distances it travels, and costs can be high. The technical challenges of managing data and avoiding interference with other satellites also are substantial, and require navigating the UN bureaucracy that assigns radio spectrum to broadcast data to and from satellites.

For Musk, satellite internet is a way to help fulfill the promise of his young company. SpaceX already has proven itself adept at efficiently making space hardware. Now the firm’s founders and investors hope it can develop ultra-cheap launch services to unlock the potential of orbital businesses. The most obvious route is using new, small-satellite technology to create potential of large-scale, low-earth-orbit constellations that solve some of the traditional problems of satellite communications, including the high cost and risk of large satellites and spotty coverage. Many of SpaceX’s investors also are invested in Planet Labs, another satellite imaging startup.

SpaceX wouldn’t comment on Musk’s satellite plans, and wouldn’t confirm a Wall Street Journal report that it plans to develop a 700-satellite constellation in low-earth orbit to provide internet service. (A constellation that size would represent a 60% increase in the number of satellites orbiting earth.)

Facebook, Google

SpaceX isn’t the only company interested in satellite internet. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg has aired his interest in the technology, and Google has been putting money behind satellite internet projects since at least 2008. That year, Google invested in O3b, founded by telecom entrepreneur Greg Wyler to help businesses provide internet access to “the other 3 billion”—the unconnected citizens of emerging markets. O3b’s eight satellites provide “backhaul” service, replacing big fiber-optic cables in remote locations, but not connecting directly to internet users.

Wyler left his CEO job a year later, after O3b was acquired by SES, the European satellite giant. In 2013, he joined Google directly, along with O3b’s former chief technology officer. Google announced plans to invest $1 billion in efforts, led by Wyler, to launch a constellation of satellites delivering internet directly to consumers. Just as with O3b, the effort would use spectrum once assigned to a failed effort, in that case Teledesic.

“This is exactly the kind of pipe dream we have seen before,” satellite consultant Roger Rusch told the industry newsletter Inside Satellite TV of Google’s plans earlier this year, predicting the costs and delays would far outstrip early projections.

And, indeed, Wyler didn’t stay at Google long. By September, he had left, reportedly to collaborate with SpaceX (paywall), though neither company would comment on his current activities. The International Telecommunications Union confirms that Wyler’s new company, WorldVu Satellites, has, along with Google, secured the rights to a suitable chunk of spectrum that was formerly assigned to SkyBridge.

2019 or bust

According to the ITU, Wyler only has until 2019 to get the network operating, or else the spectrum rights could be granted to another company. That might explain why Wyler abandoned his role at Google, possibly for a partnership with SpaceX: He reportedly was concerned that Google, primarily a software firm, lacked the manufacturing expertise to build and launch satellites before his regulatory permissions expire. (Quartz could not reach Wyler to comment.)

While Google reportedly remains set on its own satellite plan—it recently acquired SkyBox, an earth-imaging satellite firm—the company may no longer have access to the spectrum it will need to operate a network if WorldVu is indeed partnering with SpaceX, setting the stage for a potential conflict.