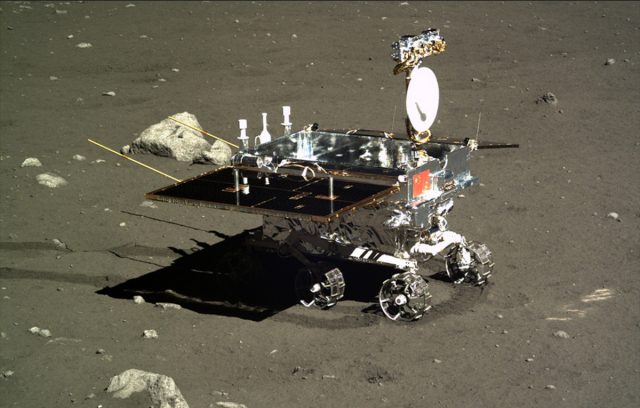

Nearly two years ago, China became only the third country to make a soft landing on the moon when its Chang’e 3 spacecraft successfully deployed the Yutu rover. Now China appears increasingly set on doing the same thing on Mars.

This week at the 17th China International Industry Fair in Shanghai, the country’s Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation unveiled a model of a planned probe to Mars. Several Chinese news outlets have reported that the country’s space program continues to progress toward the launch of a robotic mission to Mars in 2020, including both an orbiting spacecraft as well as a lander.

China made an initial but unsuccessful attempt to reach Mars in November 2011 with its Yinghuo-1 spacecraft. However, that orbiter, a secondary payload on a Russian mission to the Mars moon of Phobos, was lost after the Russian Phobos-Grunt spacecraft failed to make the required number of burns to exit Earth orbit. Both the Russian and Chinese spacecraft eventually disintegrated over the Pacific Ocean as they fell through the atmosphere.

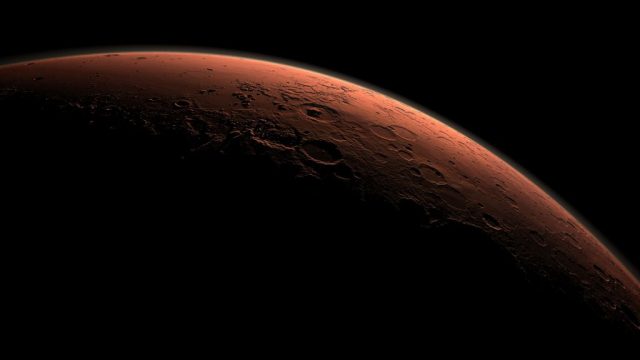

That failure dampened some of China’s enthusiasm for Mars, but NASA’s recent discovery of periodic, briny water flows on the red planet appears to have renewed the Chinese space agency’s interest.

In late September, The Global Times, an English-language version of the People’s Daily newspaper that offers a communist Chinese perspective on the news, published an editorial that hailed NASA’s findings and called for an increased focus on Mars exploration.

“NASA's far sight and one discovery after another have met our curiosity and gained respect from the world, including the Chinese people. At the same time, its discoveries give us a sense of urgency,” the editorial stated. “Perhaps it is time China sets up a special organization for space exploration. Its tasks should not be limited to Earth-related things like launching satellites. It needs to eye the solar system, the galaxy, and the universe. It should work on things that satisfy people's curiosity and widen humanity’s horizons.”

China may also be feeling pressure from the success of its regional competitor in Asia, India, which successfully inserted its Mangalyaan spacecraft into orbit around Mars in 2014. Earlier this year, to celebrate the success of the mission, the Indian Space Research Organization released an atlas of the red planet based upon images and other data captured by its orbiter.

In other ways, however, China is far ahead of India and nearly all other nations in space. After Russia and the United States, it is only the third country to launch humans into space. And with NASA's space shuttle now retired and commercial crew replacements not yet in place, China is one of only two countries currently with that capacity. Moreover, it has plans to build a space station in low-Earth orbit beginning around 2020.

The country also has an active moon program, with two lunar orbiters and the successful Chang’e 3 lander. The Yutu rover, which carried a ground-penetrating radar capable of seeing 100 meters below ground, had the capacity to detect lava tunnels that humans might use for settlement. It also had a spectrometer capable of analyzing the chemical composition of the lunar surface. With subsequent missions, China plans to return lunar samples to Earth.

These activities led some US space entrepreneurs to speculate that China is making initial preparations for building a human base on the moon by around 2030. Robert Bigelow, founder of inflatable space station maker Bigelow Aerospace, said that China may be making a land grab both for lunar resources as well as the prestige of upstaging the US Apollo landings.

Whatever China’s ultimate intentions are, they will likely remain obscure to the outside world for some time. The country selectively discloses its space activities, and with Congress preventing NASA from having formal contact with Chinese space officials, American space experts have limited access to information about their programs.

This is plain enough to Joan Johnson-Freese, a national security expert at the Naval War College who closely tracks international space programs. “Monitoring a rapidly developing China, whose language is unknown to most Americans and whose government is obsessed with secrecy, requires a degree of speculation,” she wrote. “Perhaps by design, China makes it hard to separate fact from fiction and intent from aspiration.”

reader comments

102