On Thursday evening, a Cygnus spacecraft will blast off from Cape Canaveral, strapped on top of an Atlas V rocket. The vessel will be delivering food, clothes, and science experiments to astronauts on board the ISS. It's a routine resupply. But for Orbital, this one is a little different: It's the company's first launch since a disastrous day last fall.

On October 28, 2014, the Cygnus rode atop the Orbital Antares rocket for a launch from the Wallops Island spaceport in Virginia. But six seconds into the flight, something went wrong. Today, NASA, Orbital, and other agencies are still working out exactly what went wrong, but we know this: The rocket didn't make it far off the launch pad. Instead, it began to smoke. It began to wobble. And then it exploded.

Not so long ago, Orbital was a commercial space company known for small satellites, planetary spacecraft, and other small payload launches. Its Antares rocket was its first foray into medium-lift, payload-rich rockets, a way for the firm to move beyond satellite launches and establish itself as a new industry heavyweight, joining SpaceX in carrying supplies for NASA. But on the fifth launch, Orbital watched the Antares explode right before its eyes. And as it tried to figure out what went wrong, Orbital also had to get back to space and fulfill its obligation. The shape of the company's future is at stake: It's currently competing for the next round of resupply contracts with NASA against SpaceX and other industry heavy-hitters and upstarts.

On Thursday, it's time for Orbital 2.0, proving it can recover and thrive. So I went down to Florida to see how the engineers are trying to get back to orbit.

Meet the Deke

More than a year after the Wallops mishap, Orbital wants to pick back up where it left off. The problem is, NASA contracted the company for eight resupply missions to the ISS. Because of the explosion, Orbital now has to send up all the cargo in seven.

"We obviously had to cram more stuff into the remaining missions," Dan Tani, a veteran astronaut turned Orbital-ATK executive, said in that press event last month. "Part of the solution there was use a launch vehicle that had more performance than we had been using. For the next two missions, we'll be using Atlas V, which has more robust lift capability."

Using United Launch Alliance's Atlas V instead of its own Antares will help Orbital, but that isn't the only fix. The Cygnus craft also needs to carry more cargo per voyage on the next two missions to get back up to speed, which involved some re-engineering. Before, it was designed to carry around 5,952 lbs. Now it has to carry 7,716.

The haul for OA-4, Thursday's mission, is more than the last three resupply missions combined, Tani says. To accommodate that, the Cygnus craft's cargo volume space was increased by 25 percent. At the same time, the Cygnus' instruments were upgraded and made more compact, reducing their weight for the voyage and allowing more cargo room.

The end result is a bigger, sleeker Cygnus craft, and one with a new name. It's called Deke Slayton II, named after the NASA vet initially grounded by a heart condition in the Mercury program who went on to fly in the Apollo-Soyuz missions, paving the way for longterm space habitation and cooperation between nations often at odds. After retiring from NASA in the 1980s, he went into private aerospace ventures.

"From a commercial space point of view, from an international cooperation point of view, and just his stature, we thought it very appropriate to name this vehicle after Deke," Tani says.

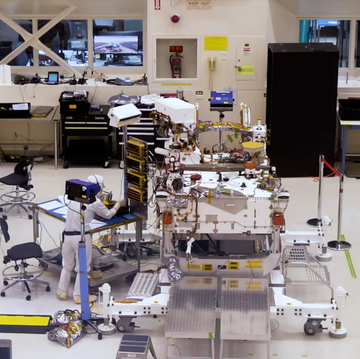

The vehicle itself looks like a giant, grooved aluminum can. Up close, it's easy to see the nuts and bolts that put a spacecraft together. It's not USS Enterprise sleek, and Orbital doesn't go for the design panache of SpaceX. It's a simple-looking craft with sophisticated, low-power instruments inside. To get to the ISS, it has to launch upward, enter orbit, match velocities with the space station, then dock with the station as it is guided in by a robotic arm. After all that cargo is unloaded, trash from the station will be loaded into the craft. The station will release the Cygnus a few weeks later, and a few thruster burns will put the unmanned spacecraft in a trajectory to burn up in the atmosphere on its way down.

When I saw Cygnus in the clean room at Cape Canaveral in mid-November, the craft was calibrated and ready, the faring ready to be fitted. The deployable solar panels were folded in. Although there was much work to be done, it was an impressive sight. Simple. Utilitarian. Borderline Soviet in its stark design. Three times that design has gotten to the space station. Once, it was destroyed by its own rocket. The next attempt is ready to go.

The excitement from NASA, Orbital, and the ULA is palpable; the people at the Cape are all smiles despite the challenges ahead. Some confidence probably comes from the fact that the ULA's Atlas V has only failed once, when a third stage failed to fire correctly, out of 103 flights, an impressive track record. Orbital's Cygnus spacecraft isn't the issue. It's the Antares rocket that's the trouble, and fixing it will decide the company's future.

Rebuilding the Antares

Buying the Atlas V launches is a tide-me-over. By next May's flight to the ISS, Orbital hopes, the Antares rocket that went terribly wrong last October will be ready to roar again.

"We're just really excited to get back flying, and time's gone by fast," Kurt Eberly, deputy project director of the Antares program, said in a phone interview. "Purchasing the Atlas flights allows us to get cargo flowing to the space station, and allows us time to work on the Antares and get it ready to launch again."

The big piece of fixing Antares is jettisoning the Aerojet Rocketdyne AJ-26 rocket engine that powers the first stage. In its place, Orbital will use the RD-181, an engine built by Russian rocket builders NPO Energomash. That engine is very similar to the RD-180, a rocket engine used by United Launch Alliance (a Boeing-Lockheed Martin collaboration) in the Atlas V.

"That engine has an outstanding reliability record," Eberly said of the RD-180. "They're up to 65 successful Atlas launches." And for that reason, Eberly says, Orbital is changing as little as possible about the rocket. The same tanks and pressurization system are in place. New feed lines and thrust adapters were required, but the craft will otherwise appear virtually the same.

"We tried to take a conservative approach where we're not trying to turn this thing into a hot rod, just get it flying as soon as we can," Eberly says.

Because Orbital is not contracted for Department of Defense launches, it can use a Russian-made engine without running afoul of international sanctions. Eberly says the company would prefer to buy something made in the USA, but "there really is no good option that's domestically manufactured." He mentioned there has been some communication with Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos' upstart company that's expected to deliver a first stage engine for future ULA rockets with the BE-4. A variation could be used in future Antares vehicles.

For now, the new Russian engine should solve the problem that destroyed the Orb-3 craft: the turbopump in the AJ-26 engine. That same turbopump nearly derailed Orb-2 in May 2014, and was identified early on as the culprit of the Orb-3 destruction. Orbital would not comment on the exact cause of the October disaster at Wallops, pending the results of an investigation being made public, suffice it to say that the AJ-26 had to go. It had never worked well when the design was part of the Soviet space program and called the NK-33. Things didn't get much better when Aerojet took over the design.

The RD-181 should prove much more reliable. The engine's certification testing is complete and four models have successfully completed verification testing. The next step is first-stage core testing, where the engines will be fired at the launch complex in Wallops, simulating a real flight.

Frenemies in Space

"It's obviously a big launch for us," Tani says, while showing off the Cygnus vehicle in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility clean room at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral. "The Commercial Resupply contract we have is one of the biggest contracts we carry in the company. We have a moral and a financial obligation to deliver the cargo spacing."

But to fulfill that obligation, Orbital is collaborating with a company it was suing just a couple of years ago. Around the time of Orb-2, Orbital (then called Orbital Sciences) launched an anti-trust lawsuit against the United Launch Alliance, reportedly over the ULA blocking Orbital's acquisition of the RD-180 engine, the one that's used in the Atlas V. Even before the Wallops disaster, Orbital was thinking about phasing out the AJ-26. The lawsuit was later dropped when a resolution was reached.

The animus didn't last long. Shortly after the Orb-3 Antares explosion, Orbital was scrambling to find a launch provider so it could get its ISS flight back on track. Space is a small world, and so they turned to erstwhile rival ULA to complete their mission contract. The OA-4 will launch on December 3, while the OA-6 will launch in March. One of the biggest deciding factors in the Atlas V was the compatibility with the Cygnus craft. But another was timing: ULA had the vehicle and capacity for a flight in that window, and Orbital had to jump on it "otherwise we might lose it to somebody else," Tani says.

At the event, there's no sign of animosity between the two parties.

"I couldn't be more excited," Kevin Leslie, ULA's mission manager for OA-4 tells a conference room full of reporters. After all, a customer is a customer. And for ULA, there was some extra excitement in taking up the challenge of helping Orbital complete its mission.

"We signed this contract back in December, so a twelve month-turnaround on a launch is very compressed for us," Leslie says. "It's very nice and humbling that Orbital ATK and NASA put the confidence in ULA and this critical mission."

Still, this is a case of strange bedfellows. Boeing, one of the key stakeholders in the ULA, recently dropped its bid to participate in the CRS-2 program—the next phase in the contracts to resupply NASA. But Lockheed Martin (the other half of the ULA) is still competition with the likes of SpaceX, Orbital, and Sierra Nevada. A successful Cygnus flight this week could bolster the craft's chances at CRS-2 contracts. If the new Antares rocket launches successfully next May, that would prove Orbital's abilities to stand on its own feet again.

Orbital has a tremendous track record already. At the same time as its rocket was exploding, the Dawn spacecraft was en route to the dwarf planet Ceres, an odd world in the asteroid belt that revealed itself for the first time when Dawn arrived in orbit that March. Designs on the next big planet hunting telescope, TESS, are also swiftly underway. It has a great track record for small satellite launches in its Minotaur fleet. But for Orbital to survive as a rocket company, and to widen its base of customers, it has to have the Antares ready to go to open up three other launch windows to other customers.

"We plan to bid on commercial missions for U.S. and international customers, and we plan to onramp to the NASA Launch Services contract," Eberly says. "We're not able to bid on any of those until we have a successful launch of the new configuration."

But for now, it's just about getting the Cygnus up there.

"It's important that we re-start cargo deliveries to ISS and it's been really good working with Orbital as they prepare to do that," Randy Gordon, ISS Mission Support Officer at NASA, said. "It's very impressive that Orbital has planned their mission, moved their equipment, their people and all their operations (to Kennedy Space Center) in that short time."