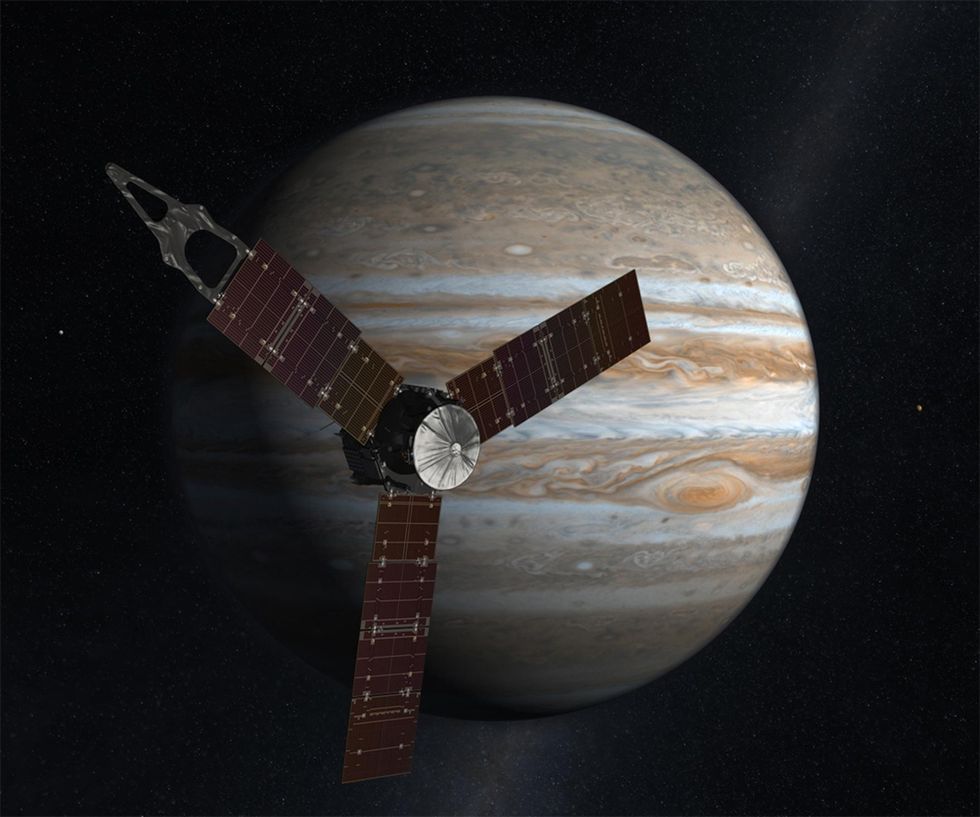

At about 9 p.m. Eastern on the Fourth of July, the Juno spacecraft will conclude a five-year journey when it carries out a series of complex maneuvers to insert itself into orbit around Jupiter. "It's both an exciting and a tense moment," says Juno principal investigator Scott Bolton. "There are many potential risks—debris, the radiation environment, the magnetic environment. There are lots of complicated maneuvers that the spacecraft has to do."

Juno has already opened its engine cover. Today, it will warm up its helium pressurant tank, which will drive rocket propellant through the fluid system for the engine burn on July 4. In three days, the final command sequence will be uploaded to the spacecraft, after which it will carry out maneuvers automatically.

The entire spacecraft is spinning at two rotations per minute; just before the rocket engine burn it will spin up to five rpm. "We have to turn the spacecraft, and we have to fire the engine at just the right time for just the right amount of time in the right direction," says Bolton. Afterward the spacecraft will spin back down to two rpm and turn around before it can transmit data back to Earth.

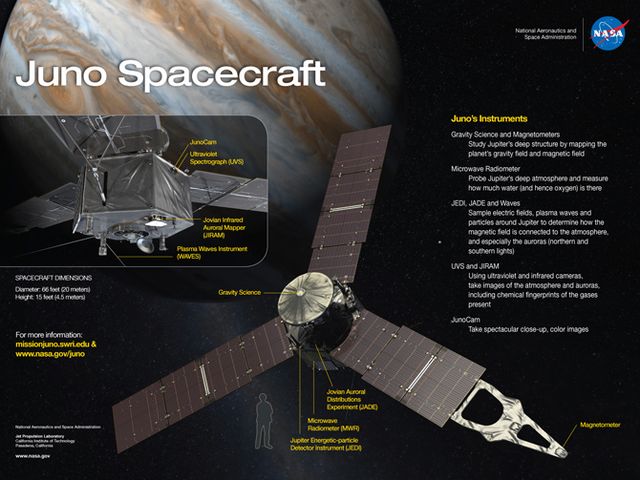

Juno is the second orbiter ever sent to the gas giant, and it has traveled farther than any solar-powered spacecraft ever launched. Each of the three solar panels on Juno stretches almost 30 feet long to harvest the sun's energy at such a distant point in the solar system.

The Jovian system is one of the most hostile places in our solar system. The radiation at Jupiter is so intense, and Juno will fly so close to the planet, that the spacecraft will only have about a year and a half to gather data before the electronics are inevitably fried (Cassini, on the other hand, has been orbiting Saturn for 12 years).

To protect the spacecraft from radiation for as long as possible, Juno has a titanium vault that shields its internal components. "We're very much an armored tank going to Jupiter," says Bolton. The vault is a "shield of armor, so to speak. It's 400 pounds of titanium walls, and it's a fairly small box."

Once in orbit, the spacecraft's primary goal will be to determine how Jupiter formed. "Jupiter has more mass and material than all the other planets combined," says Bolton. "It got the majority of the leftovers after the sun formed, so you can't really understand the formation and creation of the solar system without first figuring out, 'How did you make Jupiter?'"

The spacecraft's science instruments will map the planet, analyze the composition of the atmosphere to determine how much water is present, and measure Jupiter's magnetic and gravitational fields to help planetary scientists figure out if there is a core of solid heavy elements within Jupiter, as there is in the center of Saturn. The mission accounts for 37 polar orbits, 33 of which will travel along different longitudes to create a detailed map of the largest planet in our solar system. And Juno will be flying much lower than Galileo, the orbiter that circled Jupiter from 1995 to 2003.

"We skim across the cloud tops," says Bolton. "We're only 5,000 kilometers above the clouds. Galileo was much farther away than that."

Juno will photograph the Jovian moons, but it will not fly very close to them and the onboard science instruments are not designed to analyze the moons. This is a mission to determine how Jupiter formed and how the rest of the solar system followed.

At the end, like many spacecraft, Juno will go out in a blaze of glory. "You fire a rocket at the end to dispose of the spacecraft into the planet so that you don't accidentally crash into Europa and contaminate it," says Bolton.

How much water is in Jupiter's atmosphere? Is there a core of heavy elements? Are different parts of the planet rotating at different speeds or in different directions? How did the monstrous planet form, and what scraps did it leave behind for the other planets? By the time its mission is complete in February 2018, Juno might have provided the answers.

Jay Bennett is the associate editor of PopularMechanics.com. He has also written for Smithsonian, Popular Science and Outside Magazine.