NASA’s Glorious Ruins

A photographer finds the beauty in abandoned launch sites.

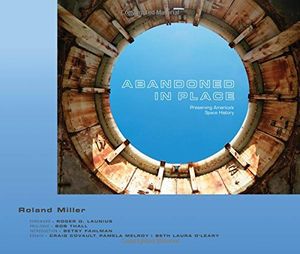

Photographer Roland Miller has spent more than 25 years documenting the now-abandoned launch facilities NASA and the U.S. Air Force used in the early days of the space program. His new book, Abandoned in Place: Preserving America’s Space History, includes more than 100 color photographs, a few published previously in Air & Space and some showing structures that have since been demolished. Miller spoke with Senior Associate Editor Diane Tedeschi.

Air & Space: Why did you decide to do this book?

Roland Miller: I think from the moment I first saw one of the abandoned launch pads, I knew they would make a good subject for a photography book.

How did you first get interested in photographing these old launch sites?

I was teaching photography at Brevard Community College near the Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral in Florida in the late 1980s. An environmental engineer from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station contacted me. He wanted my help in properly disposing of some photographic chemicals that had been discovered in an old office building. During the process of assisting him, he took me to Launch Complex 19. Launch Complex 19 is the Gemini Titan launch site where all 10 manned Gemini missions lifted off. I knew as soon as I saw the remaining buildings, launch pad, and gantry that I had to photograph them. I eventually expanded the project to include launch and test sites around the country.

How would you categorize your photography? Does it fall into a genre?

The photography crosses quite a few subject types and approaches. It is landscape, architecture, abstract, documentary—even a bit of portrait photography. In a broad sense, it is a documentary project. Within that vein, I would call it aftermath photography—photography of something that was and no longer is, at least in the same context.

What type of camera did you use for these images? Were you shooting with film?

I shot with a number of different cameras. I photographed some of the early images with an 8- by 10-inch view camera. But it quickly became apparent, based on the limited access I would have to these sites, that a large-format approach would take too much time to set up and compose the shots. So that I could document more of the launch complexes under the time constraints of being escorted to the sites by public affairs or security personnel, I switched from large-format to medium-format cameras, which allowed me to work more efficiently. Some of the most recent images were photographed with Canon digital cameras.

Have you ever gotten feedback about these images from those who worked in the space program—either astronauts or launch engineers?

Yes, both directly and indirectly. One of the first exhibits of the work was at the Brevard Art Museum in Melbourne, Florida. The curator told me stories of retired space workers who came to see the exhibition and were moved to tears. My assumption has always been that these sites brought back memories, much like visiting a childhood home. I also believe it’s hard for those who worked at the sites when they were active to see them now in a state of decline.

More than half of the space launch facilities you’ve photographed no longer exist. How does that make you feel? Should these sites be protected by historic preservation?

Photographically preserving these historic sites felt like a great responsibility. It was obvious even from my first visit to Complex 19 that these facilities could not stand up to the harsh coastal environment. The majority of the metal structures were already too far decayed to preserve. Along with the restoration costs is the fact that Cape Canaveral is relatively unique real estate for launching rockets. A number of the deactivated launch pads have been or will be repurposed for new launch systems and rockets, and I support this repurposing. It’s more important that we keep exploring than preserve every abandoned launch site. That being said, there are a few sites that should be preserved. Launch Complex 34 is the site of Apollo 7 and the Apollo 1 fire. And Launch Complex 31/32, a deactivated Minuteman facility, is the burial site of the remains of the space shuttle Challenger. Many people consider these places hallowed ground. Thankfully, I know of no plans to disturb either of these sites.

What do you want people to feel or be reminded of when they see these images?

I hope they will see a time when people worked together to accomplish an amazing feat. I hope that the book and these images will help inspire future interest in space exploration and seed young minds with the idea that anything is possible if people work together.