What’s all the excitement about?

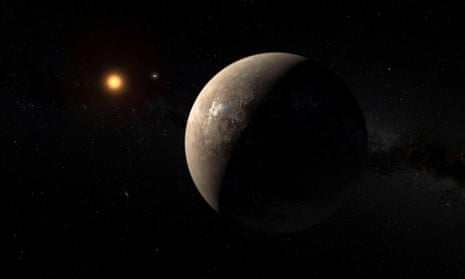

Scientists have discovered a planet, called Proxima b, orbiting the closest star to our sun – a red dwarf known as Proxima Centauri, which lies 4.2 light years away. What’s more, there are clues that it could, potentially, have some similarities to Earth.

Does this mean we’ve found a second home/alien civilisation?

No. We don’t even know for sure that Proxima b is a rocky planet, although researchers think this is likely, judging by other planets orbiting small stars. What we do know is that it is within the so-called “habitable zone”, meaning that if water is present on the planet, it could be in liquid form. But many important questions are as yet unanswered. We don’t know if the planet has water, or an atmosphere, or a magnetic field to shield it from the high-energy radiation emitted by its star. What is likely is that the newly discovered planet is “tidally locked” to its star, meaning that only one side receives sunlight. Proxima b might be within the habitable zone, but whether it could host life is quite a different matter.

How do we know it’s there?

Astronomers have not seen the planet directly, but have detected it from its influence on its star, using instruments at the European Southern Observatory in Chile. While a star exerts a gravitational tug on a nearby planet, the planet also exerts a smaller tug on the star, meaning that the star “wobbles” a little as the planet travels around it. This wobble can be spotted in the light emitted by the star – as the star moves towards us, its light appears slightly bluer, and as it moves away, it appears redder. By looking at the timing of this wobble, scientists can work out how long it takes for the planet to orbit the star, and its distance from the star, while the mass of the planet affects just how big the wobble is. In the case of Proxima b, the planet takes 11.2 days to travel around Proxima Centauri at a distance of around 7.5m km (4.5m miles) from it – that’s about 5% of the distance between the Earth and our sun. The mass of the newly discovered planet is thought to be at least 1.3 times that of the Earth.

How many other similar planets could be out there?

Thousands of exoplanets – planets outside our solar system – have been found to date. The first confirmed discoveries were in 1992, when astronomers found planets orbiting a type of neutron star known as a pulsar. The first planet orbiting a sun-like star was discovered in 1995. Since then, missions such as the Kepler space observatory, as well as ground-based observations, have found many more, including a number of Earth-sized worlds within the habitable zone of their stars. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Based on Kepler’s results, astronomers have suggested there could be as many as 40bn habitable, Earth-sized planets in our galaxy, travelling around red dwarfs or stars similar to our sun (yellow dwarfs). But with Proxima Centauri our nearest stellar neighbour, none of these planets would be as close as Proxima b.

When will we know more about it?

That depends. That Proxima b is, relatively, so close makes it an exciting prospect for scientists trying to probe the nature of other planets. But there’s a hitch: scientists are trying to figure out if it is possible to see Proxima b pass across the face of its star – a process known as a transit. If it does, it will help to pin down many details of the planet’s makeup, including its size, atmosphere and density, which will shed light on whether the planet is indeed rocky. Unfortunately, the chances of being able to see such a transit are rather small. But there are other ways of probing the Proxima b. Using the European Extremely Large Telescope, which is currently under construction, it might be possible to capture a direct image of the planet. The James Webb space telescope, set to launch in 2018, might be able to shed light on whether or not the planet has an atmosphere, and if it does, what it is made of.

Will anyone from Earth ever get near it?

That’s unlikely, to say the least. Using current technology, it would take around 70,000 years for a probe to reach the planet, although emerging technology could halve that. Further, ambitious projects, such as Yuri Milner’s $100m Breakthrough Starshot initiative, plan to create miniature space probes that would be propelled by light beams and travel at speeds of up to 100m mph, meaning that it could reach Proxima Centauri within a matter of decades.

Is the newly discovered planet part of a solar system like ours, with a group of other planets?

We don’t yet know. Scientists say they have also spotted a second, weaker signal, but it is too early to say whether that could be another orbiting body.

Do astrophysicists think there is life elsewhere in the universe?

Most seem sanguine – but whether or not there is, has been, or ever will be life on Proxima b remains a mystery, for now at least.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion