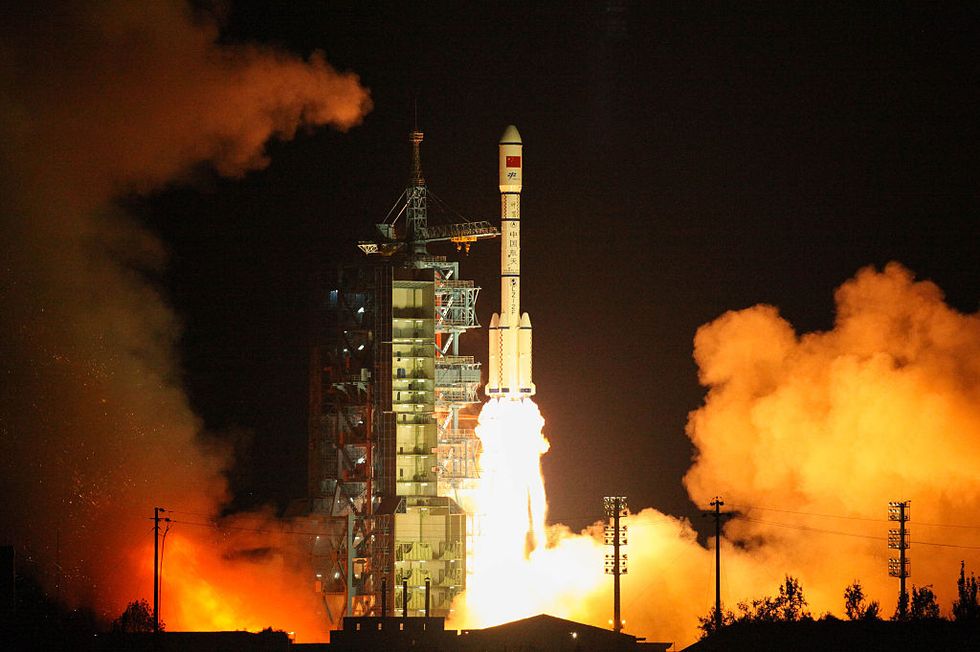

It's been a banner year for China's spacefaring ambitions. The country launched satellites to test quantum communications and search fordark matter, builtthe world's largest radio telescope, and launched a new space station into orbit (though its old one is about to come crashing back to Earth). It seems that the country is well on its way to becoming the "space giant" its president envisioned in a speech earlier this year.

Getting to this point has been a long time coming. After half a century of watching Russia and the US go from deadly space rivals to reluctant space partners, China saw its emergence as a global superpower written in the stars. Yet the last few decades have seen the Chinese cut out of major multinational orbital projects like the International Space Station.

Now, as China's space aspirations have become increasingly sophisticated, established space players such as the European Union and Russia have sought to collaborate with China on future missions. The United States, on the other hand, remains staunchly approached to collaborating with China. Can the two countries ever learn to play nice in microgravity? And what happens if they don't?

"Two Bombs, One Satellite"

China's space program was born in the aftermath of the United States' invasion of Korea in the 1950s, when Chinese leader Mao Zedong decided the People's Republic must start its own ballistic missile program to keep up with American and Soviet military developments. In 1956, Mao created the Fifth Academy of the National Defense Ministry with the goal of developing ballistic missiles (capable of deploying atomic and hydrogen bombs) and then beginning to place small satellites into orbit—a program Mao fittingly called "two bombs, one satellite."

China cooperated with the USSR on many of its early missile tests, but when Mao denounced Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev as revisionist in 1960, the USSR cut all technological assistance to the People's Republic. As a result, China's space program more or less stalled until after the Cold War, when China allowed its space agencies to begin collaborating with foreign states and capitalists. The results of this cultural pivot speak for themselves: Over the past 16 years, China became the third nation to launch astronauts (known as taikonauts) into orbit, placed two orbiters and a rover on the moon, put a handful of space stations in low-earth orbit, and outlined its plans togo to Mars in the next decade or so.

At a time when space initiatives are mostly international in scope because they're so expensive in time and money, China accomplished this its own. But for the United States, China's emergence as a spacefaring superpower has started to make the final frontier feel a little too crowded for comfort. For the first time since the Reagan years, the narrative of an impending space war has begun to permeate military and political circles.

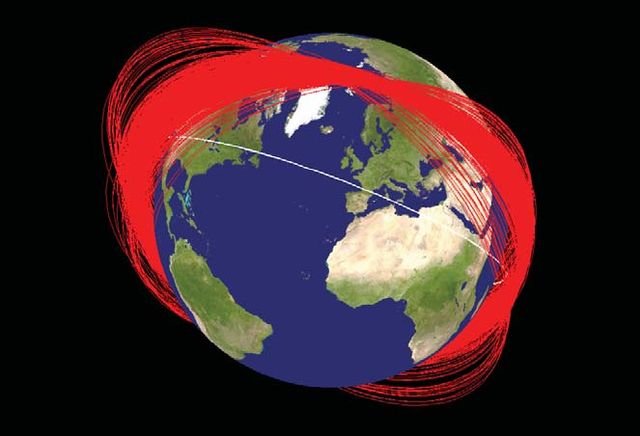

Remember 2007, when China tested an anti-satellite (ASAT) missile by blowing one of its own defunct weather satellites to smithereens? The test was a resounding success—as far as the ASAT weapon was concerned, anyway. The only problem was that the resulting explosion doubled the amount of space debris in orbit.

Since then, military folk have been wringing their hands at the possibility of orbital kinetic warfare—satellites intentionally ramming other satellites, or ground-based ASAT weapons taking out satellites in orbit—which could put expensive civilian and military space assets at risk. Moreover, there's also the possibility of a country jamming satellite radio frequencies to render critical space infrastructure useless (which isalready happening). Joan Johnson-Freese, a political science professor at the U.S. Naval War College, says that although radio jamming isn't as sexy a topic as exploding satellites, this is the more likely scenario when it comes to the hypothetical U.S.-China space war generals have been predicting for years. The reason is simple: Blowing up stuff in space ruins everything for everyone, including the aggressor.

"There Is No Flexibility"

The 2007 smash-up reminded the world of the fragility of low-earth orbit. A hostile space environment hurts everybody, and the debris generated by a kinetic space war would render low-earth orbit useless for decades. Even so, the United States hasn't managed to forge a working relationship with China that would make space war much less of a possibility.

It's not hard to see why. From the get-go, national space programs have been inextricably linked to military aims. Today's armies could not function without the satellites that provide GPS navigation, communication, and reconnaissance. Governments also are wary of space cooperation because the same rocket can be used to deliver a science experiment to orbit or a nuclear warhead to the other side of the planet. Because of this dual-use nature of space technologies, politicians and military strategists have sought to limit who has access to these systems.

To wit: Things got really chilly between American and Chinese space operations in 1998, when acongressional commission led by Christopher Cox found that technical information American space companies had given to China for use in commercial satellites wound up in improved Chinese intercontinental ballistic missiles. This effectively led to an embargo on U.S.-Chinese cooperation in space throughout the 2000s, an isolationist program reaffirmed in 2010 when former congressman Frank Wolf sponsored a bill that prohibited any sort of cooperation between NASA or the U.S. Office of Science and Technology and Chinese nationals.

"NASA was banned from bilateral relations with China as though that was somehow going to thwart or slow down Chinese plans for space," said Johnson-Freese. "In fact, if anything, it has given them an impetus to work faster and more broadly." To Johnson-Freese, the U.S. missed a big opportunity here. "Working with China, I think we would have had an opportunity to shape their space agenda. But now China has developed a very aggressive, across-the-board space program on their own and we ended up with less control, not more control."

Yet working with China is simply a non-starter for some leaders. When Wolf backed the bill prohibiting NASA-China cooperation he compared China to an "evil empire" on the scale of Nazi Germany and said the U.S. would not and should not do business with ethically questionable dictatorships. (Still, one can't ignore the fact that the United States is still paying millions to the ethically questionable government of Vladimir Putin for rides up to the ISS.) Wolf retired in 2015 and relinquished his position as Chairman of the House Appropriations Commerce, Justice, and Science Subcommittee to John Culberson, a Republican from Texas. Like his predecessor, Culberson has vowed to uphold longstanding restrictions on NASA's ability to bilaterally cooperate with China.

"China's space program is owned and controlled entirely by the People's Liberation Army and the Chinese government have proven to be the world's most aggressive in cyber-espionage," Culberson said in a statement last year. "I intend to vigorously enforce the longstanding prohibitions designed to protect America's space program." Asked for clarification on the topic, a spokesperson for Culberson told Popular Mechanics in an email that "[Culberson] is adamant about enforcing and continuing the prohibition and there is no flexibility on this." When pressed on the point that the U.S. still works with Russia, which has a nebulous distinction between its civilian and military space programs and has been accused of anti-U.S. cyber-espionage, the Culberson spokesperson maintained that "historically, working with Russia has benefited the American space program. Rep. Culberson does not see a benefit for NASA to work with China in the current climate because they've proven to be aggressive in stealing American information."

It's worth noting that politicians and military officers, not space scientists, make these policies. In 2013, a number of scientists boycotted a large NASA conference after Chinese scientists were excluded from attending. More recently, NASA Administrator Charles Bolden advocated for lifting the moratorium on U.S.-China cooperation in space and has visited Beijing to discuss ways to cooperate on removing space debris from orbit, for instance. Yet when Bolden was asked at this year's International Astronautical Congress what NASA was doing to overturn the moratorium, his answer was a frank "nothing." This was something Bolden said would "change with time," implying that the problem was political and more or less out of NASA's hands.

Made in China?

As the private space revolution has gained momentum, American companies have led the way. SpaceX and Boeing are working toward sending astronauts into orbit, while companies like Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin are planning to launch a space tourism business that carries the well-to-do into suborbital space. But now China's own new space companies are on the rise, and that's one of the factors increasing the possibility that satellite launches, asteroid mining missions, and other future space industries could be based somewhere other than the U.S. before they head off planet.

The cracks area already visible. SpaceX chief Elon Musk recently expressed irritation that American trade regulations on space technology prohibited him from hiring foreign talent to build his rockets. Asteroid mining ventures are opting to split their headquarters between the U.S. and Luxembourg after that country loosened its laws on asteroid mining while America's remain wrapped up in red tape. Once the United States saw the monetary potential in creating an environment conducive to asteroid mining, Congress quickly passed legislation that legally allowed American companies to harvest space rock while it worked out the details of how to regulate the nascent industry.

Don't expect things to open up anytime soon, though. With Bolden waiting on the politicians to make a move, and the politicians deferring to the opinions of military generals, a thawing in U.S.-China space relations in the near future does not seem likely. To Johnson-Freese, a U.S. Naval War College professor who's fully away of the need to be prepared for a space war, it's time for America to switch from an aggressive posture to a cooperative one.

"We need to tone down the battle rhetoric," said Johnson-Freese. "As bad as U.S.-Russia relations are in general right now, we continue to work together in space because both countries have a vested interest. Why don't we try to establish that vested interest with China? The time is now right."