To this day, Rahul Narayan doesn’t know why he said yes, except that it was the very last day to sign up, and if he didn’t agree to it, then there would be no Indian teams in the running. He threw together a proposal and clicked submit.

Perhaps it was the dullness of his day job in IT services, or a last-ditch effort to recapture some adolescent Star Trek-themed fantasy; but once the idea got into his head, it stuck.

And so it was decided Rahul Narayan would send a spacecraft to the moon.

Sitting in his office now, three years since his moon mission started, Narayan talks through the complexities of lunar expeditions. Sometimes, people ask him why he, a software engineer from Delhi, and a complete outsider to the space industry would attempt a lunar landing, a feat that only three countries have successfully achieved so far.

“The real answer to that,” Narayan says, “is that if you were an insider you’d never attempt something like this.”

If he succeeds, Narayan and his company TeamIndus will be the first private company ever to land on the moon.

But competition is stiff. Three other teams are competing to win Google’s Lunar XPrize for the first ever private moon landing, worth $20m. When Narayan signed up, at the end of 2011, there were 30 teams in the running. The competition’s elimination rounds have whittled it down to four.

TeamIndus is now racing against MoonExpress, led by Indian-American dot-com billionaire Naveen Jain; SpaceIL, set up by three Israeli engineers, and an international team called Synergy Moon, all planning to launch their spacecrafts in December this year. A fifth team, Japan-based Hakuto will send a rover on TeamIndus’ spacecraft which will be launched on a government-owned rocket in Chennai, and reach a top speed of 10.3km a second.

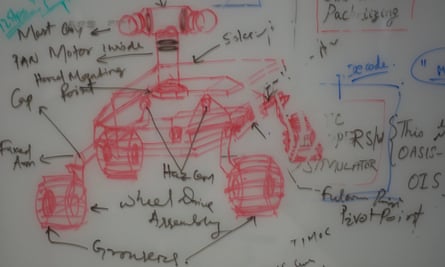

After landing at Mare Imbrium, the Sea of Showers, a four-wheeled, solar-powered, aluminium rover, one of the lightest ever to roam the moon’s surface will beam HD images back to earth as it makes a 500m journey.

If it completes all this successfully and before the other teams, TeamIndus will have done enough to win the Xprize. Money however, is tight. The project has raised only $16m of the $70m it will need. Private investment from friends, family members and Indian entrepreneurs make up part of the pot, selling payload on the spacecraft, corporate sponsorship and crowdfunding, the company hopes, will make up the rest of it.

Narayan started working on the moon mission in 2012, mostly in the evenings and on weekends in Delhi. After a year of juggling between his IT company and his new obsession with the moon, he decided it had to be one or the other, and so left the company, and moved his family to Bangalore, India’s tech capital, and the headquarters of India’s space industry. His wife didn’t object. “She knows what I’m like,” he says.

TeamIndus is the only company from a developing country to attempt the moon landing. “If we could pick this as a problem statement and solve it, I think we could solve any complex engineering problem,” says Narayan.

The company has vague plans to start a satellite programme or develop solar powered drones after the moon mission. But the real ambition, says Narayan was to prove the impossible can be done. “I don’t think anybody starts something to inspire people, but because what we’re doing is exceptionally difficult, I think the impact is very clearly cultural and social,” he says.

The new space race

Narayan’s mission appears a long way from the heady days of the 60s and 70s when the US and then USSR spared no expense to explore space. The last few decades have seen some of those dreams die amid severe cuts.

But now, with the rise of China and India in the past two decades a new race for technological ascendancy began. The 37-year hiatus in lunar landings was broken by the China National Space Administration in 2013, when the Chang’e 3 sent back soil samples to earth after successfully performing the first soft landing on the moon in decades.

The Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro) plans its own first lunar landing with the launch of Chandarayaan II planned in the next few years. The Indian company’s landing however, if successful, could beat its own government to the punch, and make India the fourth nation ever to land on the moon.

Vishesh Vatsal, an aerospace engineering graduate joined TeamIndus when the company only had a handful of employees. He was hired as an intern by Narayan, despite failing technical interviews, and is now responsible for the team working on the spacecraft’s lunar descent system, one of the trickiest parts of the entire journey.

“We’re not the most elite group of Indian engineers that have come together. A lot of people used to laugh at us,” he says, recalling one of his first weeks on the job, when Narayan pushed him in front of some executives during a company review. “I gave the silliest answers possible. We got ridiculed in subtle ways,” he says.

The criticism didn’t deter them. In January 2015, TeamIndus became the last of four teams to qualify for the XPrize award.

After that, India’s space scientists started taking them seriously. A number of veteran Isro engineers signed up to help the moon landing. Some like 72-year old PS Nair had even worked on Isro’s first satellite launch in 1975, and shaped the national space mission from its infancy. “[The] goal is not going to the moon,” he says. “The goal is to empower industry and the country to do what big, giant organisations have done earlier, and that’s the goal of the XPrize too, to popularise hi-tech activity and take it out of the control of big organisations like Nasa or Isro. Thats the real motivation for many of us.”

India’s space programme is hugely controversial, especially in the west, with some campaigners arguing millions of pounds of British aid money was being misspent in India.For many, the space mission is a symbol of neglect towards India’s most impoverished citizens, while its delusional elites reach for superpower status.

Sheelika Ravishankar, head of marketing and outreach, argues the country’s ventures are a huge source of national pride. “Different parts of India care about what we’re doing in different ways,” she says, recalling an auto rickshaw driver who donated a part of his salary to TeamIndus after one of the company’s employees told him about the moon mission on his way to work, or a man who left a board meeting to donate 2m rupees (£23,800) when the cash-strapped company urgently needed to test its spacecraft.

“Folks are coming forward to say this is architecting a new India, which is technologically advanced, which is bright, which is not the last stop of IT services where you backend to the cheapest country. This is the front of technology.”

As the launch deadline draws closer, teams are working faster than ever to test and enhance their models. A misplaced particle of dust or a simple electronic malfunction could derail the whole mission.

Many see TeamIndus as underdogs in the moon race, up against teams with vast resources.

But Ravishankarsays being in the race, and in it to win, puts India on the map.

“This proves that you can get state of the art technology coming out of India. It is proof, that you don’t have you be a huge team of rocket scientists with the deepest pockets to do research. It’s also for the rest of the world to see that anybody can put together a crazy dream. I mean, how much crazier can you be than to look at the moon and say, ‘hey, I’m going there’?”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion