The prospects for life existing in our Solar System beyond Earth and finding it within a decade or two improved with two scientific findings announced Thursday by NASA. The space agency confirmed the presence of hydrogen in plumes emanating from Saturn's small moon Enceladus, and it also reported that plumes are very likely to exist on Jupiter's moon Europa.

Both of these findings are significant. It means not only that most of the ingredients required for life must exist in the oceans of Enceladus but also that a pair of probes being planned to explore Europa will have a much better chance of finding any life there. In something of an understatement, NASA's Jim Green, who oversees the agency's planetary exploration plans, said, "This is a very exciting time to be exploring the Solar System."

The findings buttress a recent focus by NASA on bulking up a program to explore these ocean worlds in the outer Solar System, including Enceladus, Europa, and Saturn's methane-covered moon Titan. This has been a principal aim in particular for Texas Republican John Culberson, who serves as chairman of the House subcommittee over NASA's budget.

"This is truly exhilarating news," he told Ars Thursday afternoon. "The findings on Enceladus and Europa reaffirm that the best place to look for extant life in the Solar System is on these ocean worlds. Almost certainly life could have evolved there, like we see in hydrothermal vents here on Earth." Culberson added that he would continue to push not only for an orbiter and lander to be sent to Europa but for a dedicated mission to Enceladus to follow thereafter.

Enceladus

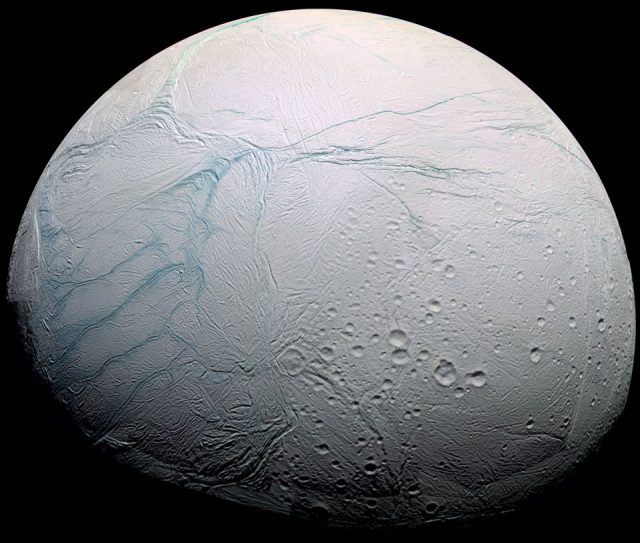

Planetary scientists weren't particularly excited about the small, icy moon of Enceladus before the Cassini spacecraft arrived in the Saturn system about 13 years ago. However, as Cassini began making observations throughout the Saturn system, scientists soon found evidence of plumes emanating from cracks in the moon's surface. Subsequent observations confirmed the existence of those plumes, plus a large ocean below the surface of Enceladus.

So as the Cassini mission neared its end, scientists planned a number of closer observations of Enceladus, including flybys through the plumes themselves. In 2015, the spacecraft made its closest approach to within 49km of the moon's surface. During that flyby, the spacecraft detected a significant amount of molecular hydrogen in the plume.

-

An artist's concept of Cassini flying through a plume on Enceladus in 2015.NASA

-

This graphic illustrates how Cassini scientists think water interacts with rock at the bottom of the ocean of Saturn's icy moon Enceladus, producing hydrogen gas.NASA/JPL-Caltech

-

A diagram of the interior of Enceladus.NASA

-

NASA

-

Another artist's concept of Cassini approaching the plumes of Enceladus.NASA

In their subsequent analysis, scientists ruled out a number of explanations for the hydrogen and concluded that it most likely formed from the interaction between warm water near a rocky core of the moon, akin to the hydrothermal vents in Earth's oceans. On Earth, large communities of microbes thrive near these vents, subsisting through a process known as methanogenesis. These organisms use carbon dioxide and hydrogen to create methane, a chemical reaction that imparts a jolt of energy for the microbe. This is how they can survive without any Solar energy.

Could such a process be unfolding within the oceans of Enceladus? Definitely, scientists said Thursday during a briefing held by NASA. Astrobiologists believe life as we know it requires water, chemical elements to make the building blocks of cells, and chemical energy. Saturn's small moon, which is only about 500km in diameter, has all three. "Now all we need to know is if Enceladus has had enough time to evolve life and make an imprint," said Mary Voytek, an astrobiology senior scientist at NASA Headquarters.

Europa

One of the four Jovian moons observed by Galileo, Europa is quite a bit larger, about the size of Earth's Moon. Scientists are confident that the ice-covered Europa also harbors a large ocean, likely much larger than that of Enceladus. And while planetary scientists are eager to explore the ocean of Europa and its potential for life, they're not sure how they're going to get through the moon's crust of ice, which is probably at least a few kilometers thick.

Using the Hubble Space Telescope in recent years, astronomers have found some evidence that, like on Enceladus, plumes may also be exiting from Europa's internal ocean into space. But they weren't sure—spying water vapor at such a great distance was tenuous at best even for the large space telescope. But on Thursday, William Sparks, an astronomer with the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, said new evidence from Hubble provides very strong evidence for plumes.

-

These composite images show a suspected plume of material erupting two years apart from the same location on Jupiter's icy moon Europa.NASA, ESA, and W. Sparks (STScI);

-

A false-color composite image of Europa taken by the Galileo spacecraft.NASA

-

The green oval highlights the plumes Hubble observed on Europa. The area also corresponds to a warm region on Europa's surface. The map is based on observations by the Galileo spacecraft.NASA/ESA/STScI/USGS

-

A cut-away image of what Europa may look like beneath the ice.NASA

-

A concept image of a lander mission NASA is planning to launch to Europa in the mid-2020s.NASA

Over the course of 12 different observations, Hubble found evidence of water vapor emanating from Europa's surface two times from the same location on the moon, near its equator, in 2014 and 2016. It was a four-sigma result, that is, there is a 99.99 percent chance the observations were not due to random chance. Moreover, the plume location lines up squarely with where the Galileo probe, which flew through the Jovian system in the 1990s, observed thermal "hot" spots on the surface of Europa. "It’s really intriguing," Sparks said. "It’s quite astonishing in fact."

The confluence of plumes at a thermal hot spot could be due to liquid water, below the ice but not too far from the surface, Sparks said. Alternatively, the plumes themselves, venting as much as 100km into space, could be raining a fine, mist vapor back onto the surface of Europa that is changing the moon's thermal character over a local area. Regardless, as NASA is planning to send both an orbiter and a lander to Europa during the 2020s, the existence of plumes would make the task of sampling the vast ocean below much simpler for scientists.

Microbes

All of this talk about oceans is exciting, but what kind of life might exist there? Certainly, no one expects to find whales, sharks, or other large sea creatures in the oceans of Europa or Enceladus. Chemosynthetic microbes seem far more likely. But really, we have no idea. If any life does exist, it would be exotic.

As to which ocean offers the best prospects for life, NASA astrobiologist Voytek said she would still bet on Europa. That Cassini found such high concentrations of hydrogen in the plumes of Enceladus may well mean that there is nothing in the moon's oceans consuming it. There is also evidence that Enceladus could be considerably younger than the moons of Jupiter, giving life less time to form there. "My money for the moment is still on Europa, but it could be on any of these moons," she said. "It would be great if life were on all of them.

reader comments

72