A Long March 7 rocket lifted off Thursday with Tianzhou 1, an unpiloted refueling freighter heading for China’s Tiangong 2 mini-space station to conduct several months of robotic demonstrations, practicing for the assembly and maintenance of a future permanently-staffed orbital research complex.

The 174-foot-tall (53-meter) kerosene-fueled launcher blasted off from the Wenchang space center, a tropical facility on Hainan Island at China’s southern frontier, at 1141:35 GMT (7:41:35 a.m. EDT; 7:41:35 p.m. Beijing time), shortly after sunset at launch site.

Lighting up the evening sky with an brilliant orange glow for a crowd of tourists, foreign dignitaries and media representatives, the Long March 7 soared through scattered clouds atop 1.6 million pounds of thrust and headed southeast to line up with the orbital path of China’s Tiangong 2 space lab, where the cargo craft will dock some time Saturday.

The Long March 7 rocket had a one-minute launch opportunity Thursday timed for roughly the moment the orbital track of Tiangong 2 passed over the Wenchang launch base, which China began constructing in 2009 and inaugurated with two successful rocket flights last year.

According to the official CCTV television network, ground crews loaded about 45,000 gallons, or 170 cubic meters, of rocket-grade kerosene fuel into the Long March 7 rocket in the hours before Thursday’s launch. Cryogenic liquid oxygen was pumped aboard the launcher after the kerosene.

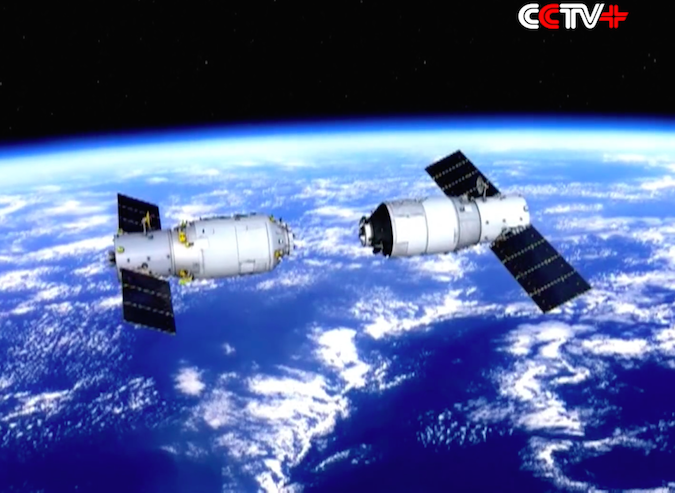

The Tianzhou 1 spacecraft fastened atop the Long March 7 rocket for Thursday’s launch carried several tons of fuel and new automatic docking equipment to test how China plans to resupply its planned space station, which could begin assembly in orbit as soon as next year with the launch of a massive core section.

At least two more modules will be added to create a 60-metric ton space station by 2022 capable of hosting three astronauts for stays of up to six months.

The two-stage Long March 7 rocket, featuring four liquid-fueled strap-on boosters, made its second launch Thursday after a successful demonstration flight from Wenchang in June 2016. The medium-lift booster is part of a new family of Chinese launchers designed to replace obsolete rockets based on missile technology that burn toxic propellants.

The four strap-on boosters, each powered by a YF-100 engine consuming kerosene and liquid oxygen, will drop away from the Long March 7’s core stage around three minutes into the flight to fall into the South China Sea. Around ten seconds later, the rocket’s two first stage YF-100 engines will cut off and jettison, then the second stage’s four YF-115 engines will ignite to power the Tianzhou 1 cargo craft into orbit.

Together with the light-class Long March 6 and heavy-lift Long March 5, the new rocket family will carry up small satellites, loft Chinese military and spy payloads, launch interplanetary probes, and place the pieces of China’s space station in orbit. Chinese officials have not said when launches of astronauts will shift to the more modern rockets.

Tianzhou 1 is the heaviest Chinese spacecraft ever launched, weighing nearly 29,000 pounds (around 13 metric tons) with a full load of propellant.

Crews on China’s space station will need fresh equipment, experiments and other supplies during long-duration missions. The longest Chinese spaceflight to date was the Shenzhou 11 crew’s visit to the Tiangong 2 space lab last year, a mission that lasted approximately 32 days.

“For example, the daily supplies of the astronauts, including food and clothing, extravehicular spacesuits, as well as drinking water with special tanks,” said Bai Mingsheng, chief designer of the Tianzhou 1 spacecraft at CASC. “We will see if the Tianzhou 1 spacecraft meets the demand of transporting and resupplying various goods through this launch.”

Tianzhou means “heavenly vessel” in Chinese.

Designed to accommodate up to 14,300 pounds (6,500 kilograms) of payloads, the Tianzhou spacecraft is similar in purpose to cargo freighters that fly to the International Space Station, such as the Russian Progress supply ship and the commercial Cygnus and Dragon carriers built by Orbital ATK and SpaceX.

In design and capability, the Tianzhou is most like Russia’s Progress and Europe’s now-retired Automated Transfer Vehicle, which carried dry goods, water and propellant to the orbiting outpost. The U.S. commercial supply ships and Japan’s HTV logistics vessel cannot refuel the space station.

“This is a new experiment,” Bai said in an interview with CCTV. “If we succeed, then the docking of manned spacecraft and cargo spacecraft will use this technology.”

The Tianzhou 1 spacecraft measures around 34.8 feet (10.6 meters) long and 11 feet (3.4 meters) in diameter. Once in orbit, the spaceship will extend its power-generating solar panels to a span of approximately 49 feet (15 meters) tip-to-tip.

“The Tianzhou 1’s carrying capability is designed according to the scale of the space station, aiming to achieve the highest carrying capacity, with the lowest structural weight,” Bai said. “There is an index for the spacecraft’s carrying capacity, or payload ratio, as it is called. The payload ratio of Tianzhou 1 reaches 0.48, which ranks fairly high in the world.”

He said the Tianzhou 1 mission is expected to last about two months, during which time the craft will dock with Tiangong 2 three times and refill the module’s liquid propellant tanks in orbit around 235 miles (380 kilometers) above Earth. China’s Xinhua news agency previously reported the Tianzhou 1 spacecraft will then fly on its own for around three months before re-entering Earth’s atmosphere.

Xinhua said the Tianzhou 1 supply ship will conduct several research experiments during its solo flight, including one on “non-Newtonian gravitation.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.