As part of rocket development, aerospace engineers extensively test booster components before they are assembled into a larger launch vehicle. To that end, NASA has built two big test stands at Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama to test its large liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen fuel tanks. These tanks are part of the core stage of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket.

However, a new report from NASA's inspector general, Paul Martin, raises serious questions about the cost of these test stands and the decision to build them in Alabama rather than in Mississippi, where NASA has an existing facility that already tests rocket engines. Additionally, the Mississippi-based Stennis Space Center is also much closer to the Louisiana factory where the SLS hydrogen and oxygen tanks are being assembled.

Costs

As part of the SLS program, NASA determined that it needed two test stands: one is for the larger hydrogen tank, which is about half the length of a football field, and the second is for the oxygen tank. The agency budgeted $40.5 million for the project but ended up spending $76 million, which is an increase of 88 percent. The stands were completed in November 2016.

The inspector found that most of the cost overruns were due to NASA's acceleration of the test-stand construction, with the space agency requesting the stands' completion by September 2015. This would have allowed the SLS rocket to make its maiden launch by the end of 2017. However, shortly after construction began, NASA delayed the maiden launch of the SLS rocket until 2018. And, recently, the agency delayed it again into 2019.

The initial launch delay came just a few months after construction began. By then, the SLS program, which is based at Marshall in northern Alabama, had already paid a $7.6 million premium to the contractor for a compressed schedule. Moreover, because plans weren't finalized before work began, NASA had to modify the construction plan six times during the course of building the test stands. This added an additional $12.1 million to the cost. Finally, despite the rush job requested, the test stands weren't completed until November 2016.

Location

The SLS program also chose to build the test stands at Marshall without considering the total cost of doing so there, versus other sites. Those costs include planning, design, operations, maintenance, and more. The consideration of different sites is normally a NASA requirement for projects costing in excess of $10 million.

The inspector general's report states:

NASA chose to build... at Marshall without adequately assessing life-cycle costs associated with other possible sites to make the most cost-effective analysis. Although teams from both Marshall and Stennis proposed designs for possible test stands, only the Marshall designs were reviewed and listed as possible alternatives at the final decision review.

The inspector's report suggests that, just as engine tests were moved to Stennis in recent decades, the agency might consider doing the same for structural tests of large fuel tanks. The relocation would be due to neighborhoods being built near the edge of Marshall and the lack of a "buffer zone" between the space center and nearby community.

In response to the inspector general, Marshall engineers said the Stennis design was eliminated because it would have cost more. (This analysis was not documented in 2012 when the decision was made, however). The report also states that Marshall engineers could provide no documentation or analysis to back up claims that building the test stands at Stennis would have led to higher maintenance costs or design issues. "In our view, once the design that best met the SLS Program's needs was chosen, the Agency should have determined the most cost efficient location to build based on analysis of all potential locations," the report says.

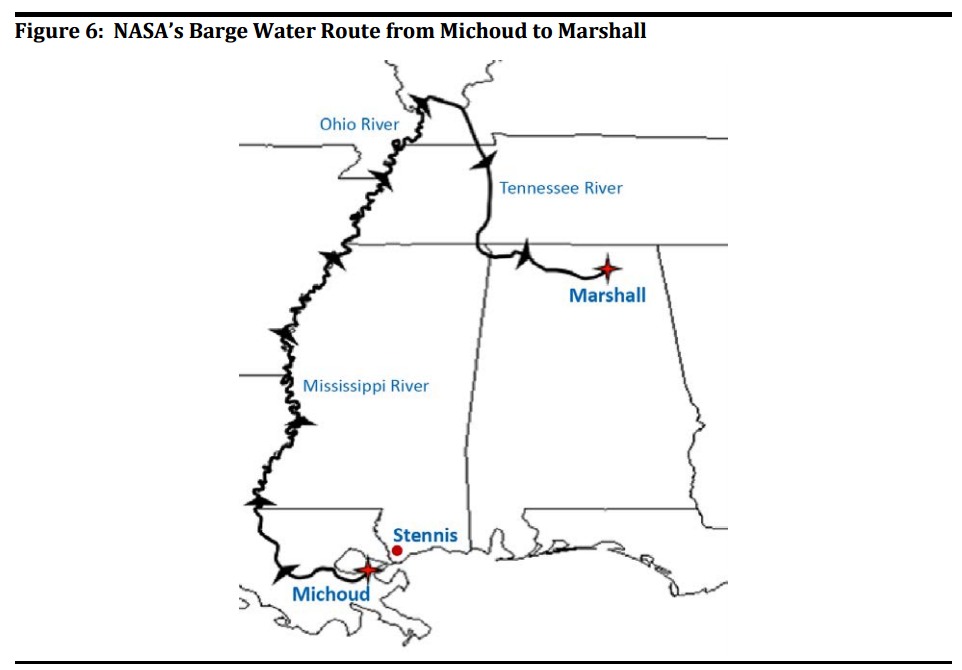

Finally, the inspector general's report notes that building the test stands at Stennis made more sense from a geographical standpoint. After the fuel tanks are built at Michoud Assembly Facility in southeastern Louisiana, they must be shipped by barge to the test stands. Stennis is only about 40 miles away, whereas Marshall lies 1,240 miles away and requires navigating the Mississippi, Ohio, and Tennessee rivers. Shipping a single tank from Michoud to Marshall takes about two weeks and $500,000. Sending tanks to Stennis requires less than a week and only $200,000.

The loss of a few tens of millions of federal dollars might not be much of a story but for the fact that critics have assailed NASA's rocket program as a political beast, designed to maximize jobs in the districts of key US senators and representatives. Indeed, among the most vocal of SLS proponents has been US Senator Richard Shelby. The Alabama Republican proclaimed in 2011 that “The ability of NASA to achieve our goals for future space exploration has always been and always will be through Marshall Space Flight Center."

He got his wish with the SLS fuel tanks.

reader comments

119