If you ask the Pentagon, the first space war was more than 25 years ago.

"People reference Desert Storm as the first space war," General John W. "Jay" Raymond, commander of Air Force Space Command (AFSPC), said during a recent visit to the Popular Mechanics offices in New York. "It really was the first time that we took strategic space information and integrated it into a theater of operations."

The "left hook" of Operation Desert Storm, when U.S. and allied ground forces attacked the western flank of the Iraqi military in Kuwait, revealed the true power of satellites in wartime. "Going through a desert, at night, without roads and maps—it was all enabled by GPS," Raymond says.

Fast-forward a quarter-century and tensions are again on the rise, from Syria to the Korean Peninsula. And today, the United States no longer enjoys the type of control it had over space in 1991. A hypothetical attack on U.S. satellites has been a serious public concern since at least January 2007, when a Chinese missile shot a Chinese satellite out of the sky. Russia has been researching anti-satellite weapons since at least the 1980s.

The past few decades have shown how space operations can revolutionize military operations on Earth. The next theater, however, might be space itself.

"Both [Russia and China] will continue to pursue a full range of anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons as a means to reduce U.S. military effectiveness," said Daniel Coats, Director of National Intelligence, in a congressional testimony released in May. Last week, Republican Sen. Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma put it another way while questioning the nominee for NASA Administrator, Jim Bridenstine. "We are in the most threatened position in the history of the country," the senator warned.

The rhetoric coming out of Washington can make it seem as though we are headed into a future of astronaut grunts and laser guns and space shuttle door gunners. A group of congressional leaders have even pushed for legislation to create a new branch of the military: the Space Corps. However, Gen. Raymond paints a slightly different picture of military operations in orbit and the role of American leadership in space.

How We Got Here

Back in 1991, as U.S. troops slogged through the deserts of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Iraq, it wasn't just GPS navigation that helped bring swift victory to American forces. One of the most effective weapons the Iraqis had during the Gulf War, Soviet-built Scud missiles, were rendered nearly useless by infrared missile-warning satellites.

While many of America's guided missiles used infrared tracking in the 1990s, "today every weapon we're employing in Iraq and Syria is a precision weapon, and the vast majority are GPS-enabled ones," Raymond says. More than ever, the armed forces are augmented by orbital eyes in the sky.

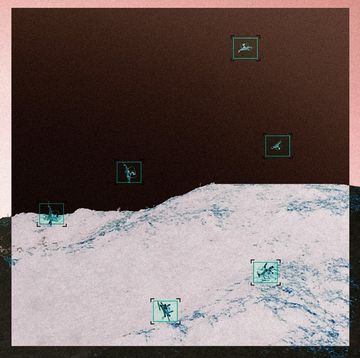

"There's nothing we do today, there's not a sailor, soldier, or marine that operates in their domain that isn't using space capabilities to conduct their mission," says Raymond. Perhaps the most direct example of space assisting ground forces is the Android Tactical Assault Kit (ATAK), a smartphone that many troops carry on their chests to navigate terrain with GPS, coordinate strikes, set drop and evacuation zones, and generally stay in sync with friendly forces using satellite-enabled capabilities.

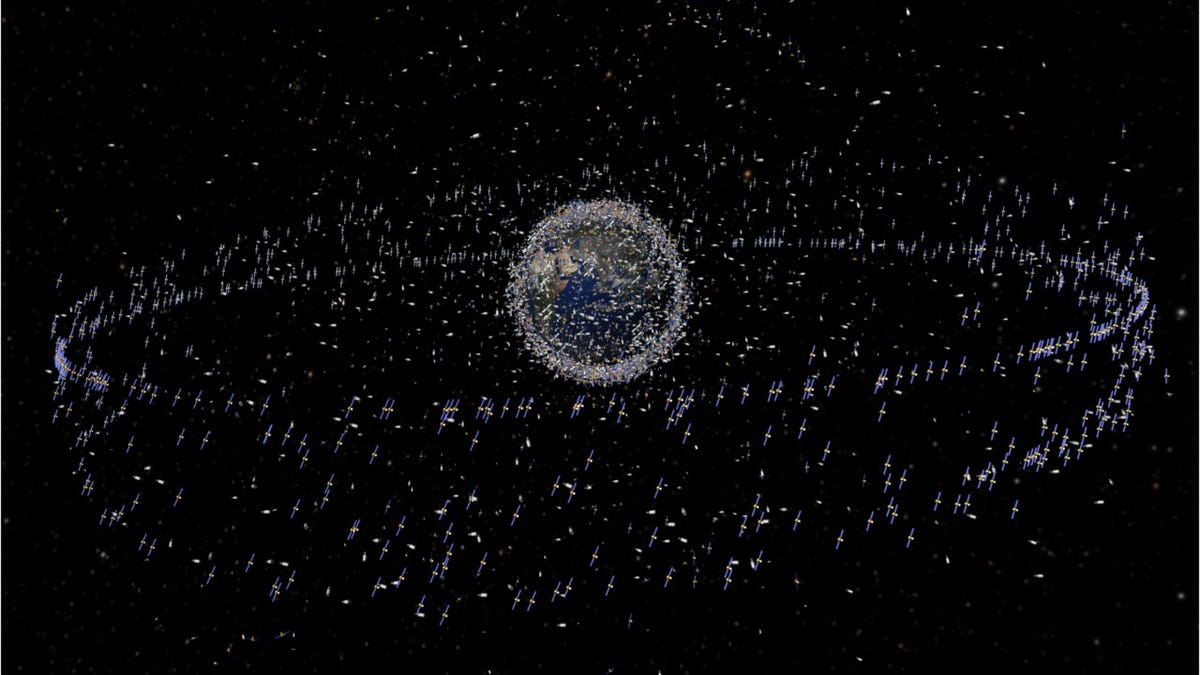

To make all that possible, Air Force Space Command operates roughly 80 satellites. You might not know it, but AFSPC is the group that makes sure Google Maps works on your phone. The command operates all 24 to 33 satellites in the GPS constellation for the entire world (though China is working to build their own GPS network of 30 satellites). AFSPC also tracks 23,000 objects in orbit, 1,400 of which are active satellites, using ground-based radar. If the space command detects a possible collision, they notify the satellite owners, regardless of what country or company the satellite belongs to.

America's increasing reliance on those satellites makes them a ripe target for a potential adversary. The United States has enjoyed essentially unchecked control of orbital domains for almost half a century, and while other nations are catching up, U.S. military leaders intend to maintain that control. "Space is foundational to our way of war," says Raymond, "and it's foundational to our way of life."

Stopping a Space Attack

How do you stop another powerful country from taking out your satellites?

"There are vast ways," says Raymond, "and I won't get into the operational details of what we may or may not be able to do, but we're working on being able to protect and defend capabilities from everything from low-end reversible jamming all the way up to the higher-end kinetic activities."

"Kinetic" is the military's favorite euphemism for lethal force via missiles, bullets and the like. In this case, it means destroying a satellite with a weapon that physically smashes into it. Whether the U.S. or other countries are planning to put weapons in orbit—either to kill other satellites or to strike the ground—is classified information. When asked about weapons in space, Raymond simply said, "I'm not going to talk about that." Given the stakes, it's safe to assume that such capabilities are being discussed if not already designed.

But kinetic operations are only a small part of military deterrence. Arguably the most crucial capability, particularly in orbit, is simply knowing where everything is and what it's doing.

"We have four geosynchronous space situational awareness program satellites that actually drift just below the geo belt, kind of the neighborhood watch for space," the general says. These sats augment the ground-based radar that AFSPC uses to track objects in orbit, giving the space command a comprehensive picture of what's going on beyond the reaches of the atmosphere.

AFSPC also gets an assist from one of the United States' premier spy institutions, the National Reconnaissance Office. "We work very closely with the National Reconnaissance Office," Raymond says. "It's our strongest partner." The Air Force is working along with the spy agency to develop a fleet of spacecraft by 2030 that could detect and deter threats, and if necessary, take them out. Information is key, as whichever country has the most complete picture of orbit will likely control the domain.

Guarding America's space assets against attack is a relatively new frontier for the Pentagon. Arguably, however, the more mundane part of the mission is the most important. That is: coordinating the trajectories of tens of thousands of objects encircling the planet in an increasingly crowded and dangerous space.

Space Traffic Control

To defend American spacecraft in orbit, Air Force Space Command often finds itself in the curious position of helping other countries to prevent collisions. "About once every three days a satellite maneuvers to keep from hitting something," Raymond says. "About three times a year the International Space Station maneuvers to keep from hitting debris."

In a worst case scenario, colliding spacecraft could break apart into a debris shower that starts a chain reaction, striking additional spacecraft until you've got a field of swirling metal obstacles. Such a situation would be just as detrimental to U.S. space capabilities as a Chinese missile, if not more so.

"We act as the space traffic control for the world," says Raymond. "It's not in anybody's best interest to have large debris fields."

Space traffic control is getting more challenging. Launch costs continue to fall, space is more crowded than ever, and many satellite operators are using numerous small satellites, such as CubeSats, to replace the bigger, multi-purpose satellites that were prioritized in the past. The variable mission of AFSPC becomes a balancing act between defense—supporting U.S. warfighters with information from orbit—and safeguarding the planet's congested orbital planes so space remains free and open to exploration and scientific research.

Orbit Gets Busy

As for launching its own equipment into orbit, AFSPC plans to expand cooperation with private spaceflight companies. SpaceX in particular has impressed Gen. Raymond. It's not just rocket reusability that drives down costs, he says, but also the autonomous capabilities that SpaceX has built into the Falcon 9 launch vehicle.

"They've built autonomy into their rockets," says Raymond of SpaceX. In the past, a range operator would need to monitor telemetry and radar data from the ground and blow the rocket manually if it went off course. "With SpaceX now... if that launch vehicle launches and it starts to go astray, it senses itself that it's gone past the point where it could impact safety and it blows itself up."

Thanks to new technologies from companies like SpaceX, more rockets will be launched in the coming years than at any other point in history. Earth's orbits will be filled with imaging satellites and broadband satellites and weather satellites and science experiments and whatever else people dream up to send to space. Air Force Space Command, the orbital police, if there is one, is busy preparing for this inevitability.

Jay Bennett is the associate editor of PopularMechanics.com. He has also written for Smithsonian, Popular Science and Outside Magazine.