Astronomers have spotted a “zombie star” that refused to die when massive explosions that are normally considered fatal rocked the heavenly body.

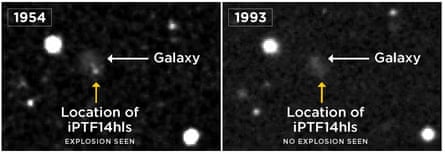

The star, which lies half a billion light years away in the constellation of the Great Bear, has exploded multiple times since 1954, but may finally be on its way to the cosmic graveyard.

It is the first time astronomers have seen the same star explode over and over. Until now stellar explosions, or supernovae, have been considered singular events, the dazzling death throes of stars that have burned up all their fuel.

Q&AWhat is a supernova?

Show

Supernovae are exploding stars. The violent events are the largest explosions in space and can shine for months and even years with the brightness of 100m suns. A star can explode in one of two ways. The first type of supernova happens when a white dwarf star made from carbon and oxygen attracts material from another star that it orbits. The white dwarf grows steadily until the density of its core becomes so high that the carbon and oxygen fuse in a runaway reaction that drives the explosion. The second, more common, type of supernova happens when stars burn up their nuclear fuel and cannot withstand their own gravity. The core of the star collapses but triggers a massive explosion. Many common elements are forged inside stars and are scattered through space by supernovae, where they go on to form new stars and planets.

“This is the weirdest supernova we’ve ever seen. It’s the first time we’ve seen multiple explosions in the same place,” said Iair Arcavi, an astronomer at Las Cumbres Observatory in California. There is no known theory that explains the observation.

The curious incident came to light after astronomers detected a supernova in September 2014 with the Intermediate Palomar Transient Factory (iPTF) telescope near San Diego. The exploding star seemed unremarkable at first, but observations four months later showed that rather than dimming over time as expected, the supernova had actually become brighter.

At first, Arcavi thought that a nearby star in the Milky Way had simply wandered into the same position and blocked out the supernova. “I probably would have bet my car on it, but I’m glad I didn’t. We were astonished to find that it was the supernova,” he said.

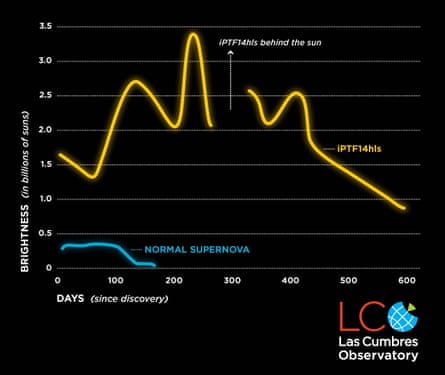

When stars explode at the end of their lives, they can shine with the brightness of 100 million suns for three months or more before they fade into the darkness. The 2014 supernova, named iPTF14hls, shone for more than two years, during which its brightness rose and fell at least five times. An even earlier explosion appears to have happened in 1954 when a burst of light was detected from the same location. The group’s calculations show there is a 95 to 99% chance it was the same star.

The astronomers ruled out the most common supernova theories, but found one that explained some of the star’s odd behaviour. According to the “pulsational pair-instability model”, stars with masses of at least 100 suns can explode multiple times before dying, with each blast sending vast amounts of material into space. Now and again, material rushing away from the star can catch up with older ejected material, producing bright flashes of light as it collides. “The theory doesn’t explain everything, but it’s the only one that comes close,” said Arcavi.

“One thing we can tell from the supernova is how long ago the star exploded,” he added. “The weird thing is that even two years later, it looked like a two-month-old supernova.” It is as if the star exploded in slow motion.

It is impossible to know how rare multiple exploding stars are. “It’s true that this is the only one we’ve found, and it’s so bright it’s hard to miss, but it looks like the most vanilla kind of supernova there is. It’s kind of a disguise,” Arcavi said. “We don’t know how many of these we might have found but never looked at again. We may have just missed them.”

More recent observations of the star suggest that the 2014 explosion may be its last, according to details published in Nature. The astronomers have switched to larger instruments to watch the supernova fade and will soon look on with the Hubble space telescope. Before long, the centre of the supernova – where a black hole now lurks – should be visible. “We definitely plan to keep an eye on this one,” Arcavi said.

Stan Woosley, director of the Center for Supernova Research at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said understanding the supernova could throw light on the evolution of the most massive stars in the universe and the birth of certain kinds of black holes. “For now the supernova offers astronomers their greatest thrill: something they do not understand,” he said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion