EDITOR’S NOTE: Updated at 0300 GMT Saturday (10:00 p.m. Friday) with confirmation of a successful launch.

Two research satellites to probe Earth’s climate patterns and test ion engine technology to counter atmospheric drag in an unusual low-altitude orbit launched Saturday on top of a Japanese H-2A rocket.

The two Japanese-built spacecraft rocketed away from the Tanegashima Space Center in southern Japan at 0126:22 GMT Saturday (8:26:22 p.m. EST Friday) inside the H-2A’s payload fairing.

Liftoff occurred at 10:26 a.m. Saturday Japan Standard Time.

Mounted on a dual-payload adapter fixture, the satellites were released into two distinct orbits a few hundred miles above Earth by the H-2A’s upper stage.

First, the hydrogen-fueled launcher deployed the Shikisai climate monitoring satellite into a polar orbit around 500 miles (800 kilometers). Then the rocket’s LE-5B upper stage engine reignited twice, targeting a lower altitude for separation of a technological demonstration satellite named Tsubame in an elliptical orbit between 280 and 400 miles (450-643 kilometers) over the planet.

Deployment of the 2.2-ton (2-metric ton) Shikisai satellite, also known as the Global Change Observation Mission-Climate (GCOM-C), occurred around 16 minutes after the H-2A rocket’s liftoff from, a facility carved from the rocky coast of an island in southwestern Japan.

The 880-pound (400-kilogram) Tsubame payload, officially named the Super Low Altitude Test Satellite (SLATS), was released from the H-2A second stage at T+plus 1 hour, 48 minutes.

Flying on its 37th flight, the H-2A rocket headed south from Tanegashima and jettisoned two solid rocket boosters around two minutes into the flight.

The launcher’s LE-7A main engine, consuming a cryogenic mix of liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, fired for about 6 minutes, 38 seconds.

The payload shroud covering the Shikisai and Tsubame satellites separated from rocket at T+plus 4 minutes, 5 seconds.

Once the first stage completed its job, the second stage took over the flight for three engine burns to inject the payloads into the mission’s two target orbits.

The H-2A rocket blasted off from Japan 72 seconds before a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

The back-to-back liftoffs marked the shortest time between two successful orbital launch attempts since the dawn of the Space Age, according to Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who tracks global space activity.

The previous record for the shortest duration between two orbital launches was set in December 1970, when a Soviet Kosmos 3M booster and a French Diamant-B rocket lifted off from Russia and French Guiana 4 minutes, 44 seconds, apart, McDowell said.

Saturday’s successful mission was the sixth H-2A launch of the year, and the 37th straight success for Japan’s H-2A/H-2B rocket family.

The Shikisai, or GCOM-C, mission is named for the word for colors in Japanese.

The satellite follows the Shizuku, or GCOM-W, mission launched by Japan in May 2012 to study Earth’s water cycle.

The Shikisai satellite carries a wide-area global imaging instrument package — including a visible and near-infrared radiometer and an infrared scanner — to extend climate observations made by Japan’s ADEOS 2 spacecraft, which succumbed to a power failure and ended its mission in 2003.

During its planned five-year mission, the climate monitoring observatory will make “surface and atmospheric measurements related to the carbon cycle and radiation budget, such as clouds, aerosols, ocean color, vegetation, and snow and ice,” according to a fact sheet released by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency.

Scientists say Shikisai’s observations will improve their understanding of climate change, and help numerical climate models predict future changes. The imager will also track phytoplankton, aerosol, and vegetation activity to map fisheries, monitor the transport of dust, and estimate crop yields, according to JAXA.

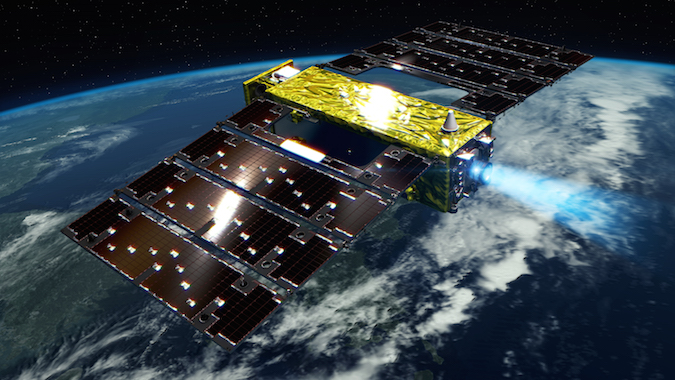

The smaller of the two satellites launched Saturday was named Tsubame, the Japanese word for swallow, after a public competition.

JAXA said Tsubame is “a perfect nickname for the thin, elongated satellite in super low orbit with a set of solar array wings – what can describe it better than the small, familiar bird flying low?”

Tsubame will use aerodynamic drag to eventually drop into an orbit below 166 miles (268 kilometers), and an ion engine powered by electricity and xenon gas will maintain its altitude between 111 miles (180 kilometers) and 166 miles, counteracting air resistance from the thicker atmosphere at that height.

Designed with aerodynamic stability in mind, Tsubame was built to operate at least two years. The small spacecraft’s ion engine produces thrust equivalent to the weight of a small coin, but it burns little fuel, allowing it to fire for weeks to months continuously.

“An orbit with an altitude lower than 300 kilometers (186 miles) is referred to as “super low orbit,” and it is an unexplored region which has yet to be fully utilized by existing satellites,” JAXA said in a fact sheet for the SLATS mission. “Satellites in a super low orbit will bring benefits such as higher resolution optical observation imagery, lower transmission power for active sensors, and cost reductions in satellite manufacturing and launches.”

A European Space Agency satellite named GOCE flew in a super-low orbit with the aid of an ion engine to measure Earth’s gravitational field and ocean circulation before running out of fuel in 2013 after a four-year mission.

The Tsubame satellite carries a camera to take pictures of Earth from orbit, and an experimental coating on the craft’s thermal insulation to prevent damage from atomic oxygen, a gas present at the orbiting testbed’s planned altitude. Atomic oxygen is known to damage the multi-layer insulation typically used on satellites, according to JAXA.

Japanese engineers want to know how the satellite responds to years of exposure to conditions at the mission’s unusual operating altitude.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.