The most recent time NASA launched a mission to Venus was in 1989. The Magellan orbiter lasted four years, transmitting data back to Earth that had to be recorded onto physical tapes. These were archaic times.

The generation-long drought of missions solely intended to study Venus was extended further last Wednesday, when NASA selected two projects as finalists for a mid-2020s science mission. None of the three Venus projects were chosen. One did receive additional funding for more research and development, but it will have to wait till the next application cycle to contend again for mission selection.

The general public might be more or less ambivalent to such a decision, but within the scientific community, there’s plenty of lamenting that Venus continues to draw the short straw when it comes to NASA’s science program.

But NASA is right. It’s time to let go of Venus.

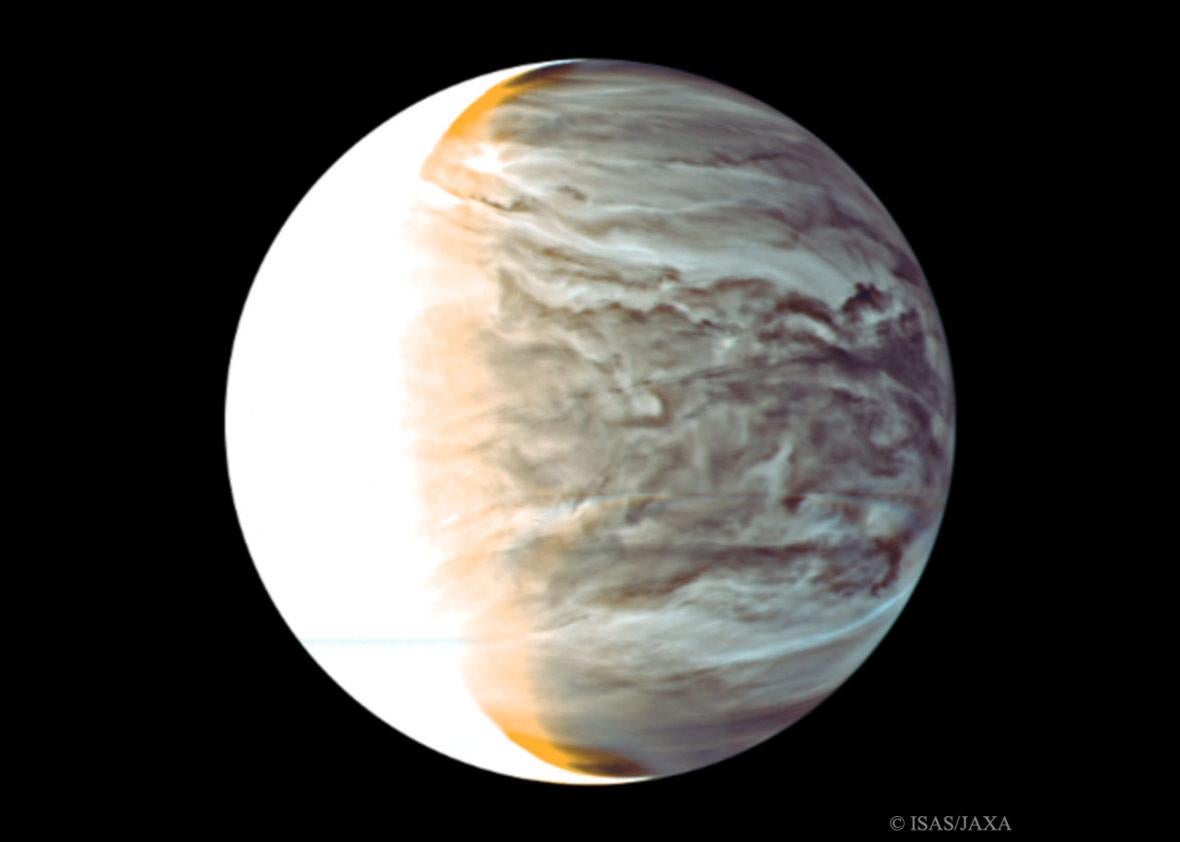

There have always been good reasons to conduct missions to Venus: Earth and Venus share comparable sizes, densities, and overall geographies, and many scientists believe Venus represents a sort of glimpse into an alternate reality of what Earth could have turned out to be. While our planet is a warm, loving environment that’s allowed life to evolve and thrive, Venus is an 850 degree Fahrenheit extraterrestrial hell, covered in a dense atmosphere of sulfuric acid and surface pressures that we only see on Earth at depths of about 1 kilometer underwater. When previous missions have gone to Venus, they’ve been searching for clues that could explain how some planets transform into habitable worlds, and others don’t. That information could be very useful for understanding what other worlds and directions we ought to focus our attention on.

But there are two major reasons it’s time to move on from Venus. The first is cost and accessibility. Jim Green, the director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, told reporters last Wednesday that going to Venus is still an incredibly difficult venture. The planet’s hellacious environment is a destructive force. Spending millions or billions of dollars on a lander that can’t last more than a few hours is a hard sell against projects that can study other worlds for several years on end, like Mars or Saturn’s moon Titan. Scientists are making strides in computer chips and technologies that could handle Venus, but a working lander or rover is still very far in the future. We could stick to orbiters and be safe, but there’s only so much you can learn about a place from high above.

The second reason to ignore Venus harkens back to what NASA is more interested in these days: extraterrestrial life. NASA is pivoting its science program deeper into astrobiology to find worlds that could be habitable to life—be it by humans or aliens. Mars, for instance, is a place we will certainly set foot on one day, and there are high hopes we could find signs of past or present microorganisms on the planet. Ocean worlds, like Saturn’s moons Titan and Enceladus and Jupiter’s moon Europa, also possess subsurface liquid oceans that might be breeding grounds for lifeforms. And even though these worlds are freezing, habitat technologies that keep colonists warm and fuzzy are already conceivable. If we can eventually perfect terraforming technologies, we could warm these worlds up so they’re more amenable to future denizens.

Venus is not like that. It’s almost certainly lifeless in its current state. We can’t even get simple instruments on Venus to survive for more than a few hours before they melt and combust. It’s almost unthinkable humans will ever set foot on the surface. And terraforming as we currently think about it means warming a planet up (which we’re pretty experienced at!), not cooling it down. If Venus ever decides to chill out, it will be millions or billions of years from now, as a natural process.

It’s sad to say, but Venus is more of a sideshow when it comes to planetary science these days. It might be time to accept we won’t be visiting the yellow planet for quite a long time. Let’s give ourselves a moment to mourn, and move on.