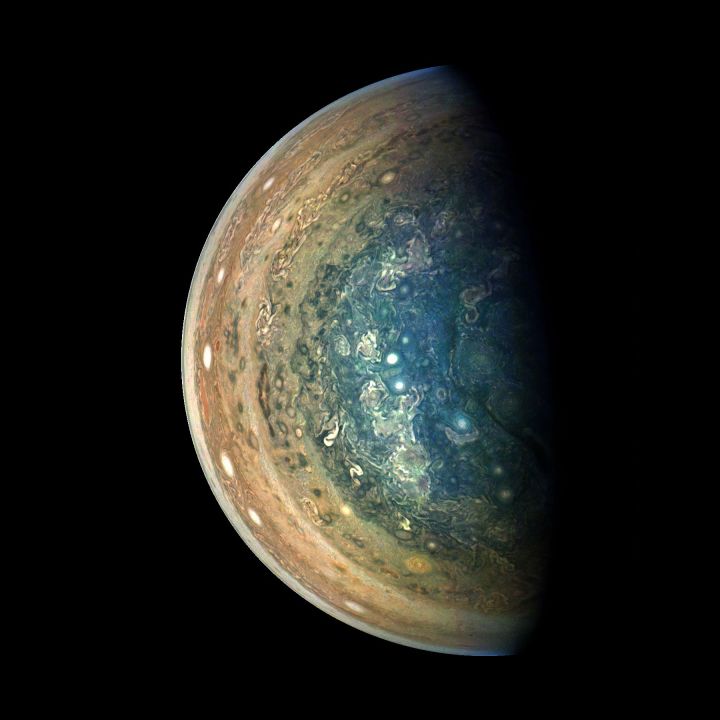

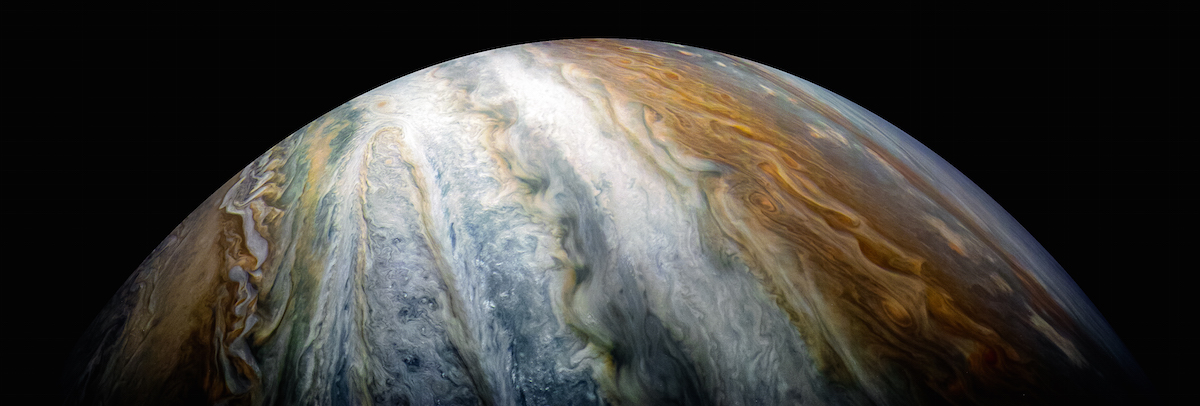

NASA’s Juno spacecraft, now on its 11th orbit around Jupiter, continues to return jaw-dropping views of the solar systems’s biggest planet from previously-unseen up-close perspectives of its colorful clouds and raging storms.

While Juno’s scientific sensors map Jupiter’s radiation belts, measure its magnetic field and peer deep inside the gas giant’s atmosphere, a camera aboard the solar-powered probe beams back colorful imagery of the planet’s complex weather patterns.

Once each orbit, Juno closes in on Jupiter for a high-speed flyby as close as 2,100 miles (3,400 kilometers) from the planet’s cloud tops, closer than any past space mission has come to the giant planet. Juno is also the first orbiter to get direct views of Jupiter’s poles.

Juno’s imaging camera, known as JunoCam, continued taking spectacular pictures during the probe’s most recent close-up encounter with Jupiter on Dec. 16.

JunoCam’s raw imagery data is downlinked back to Earth for scientists, artists and members of the public to examine, process and render into colorful pictures, revealing textures and shades of Jupiter that have been hidden from view until now.

It’s primarily an outreach tool to inspire everyday citizens with the wonders of the cosmos, but JunoCam also provides useful scientific context for researchers crunching data coming from the spacecraft’s other instruments.

Jupiter is so big that 11 Earth diameters could fit inside the planet’s disk, and Jupiter’s immense gravity pulls Juno to a speed of 129,000 mph (nearly 58 kilometers per second) on each close approach, a point in the craft’s 53-day orbit that scientists call “perijove.”

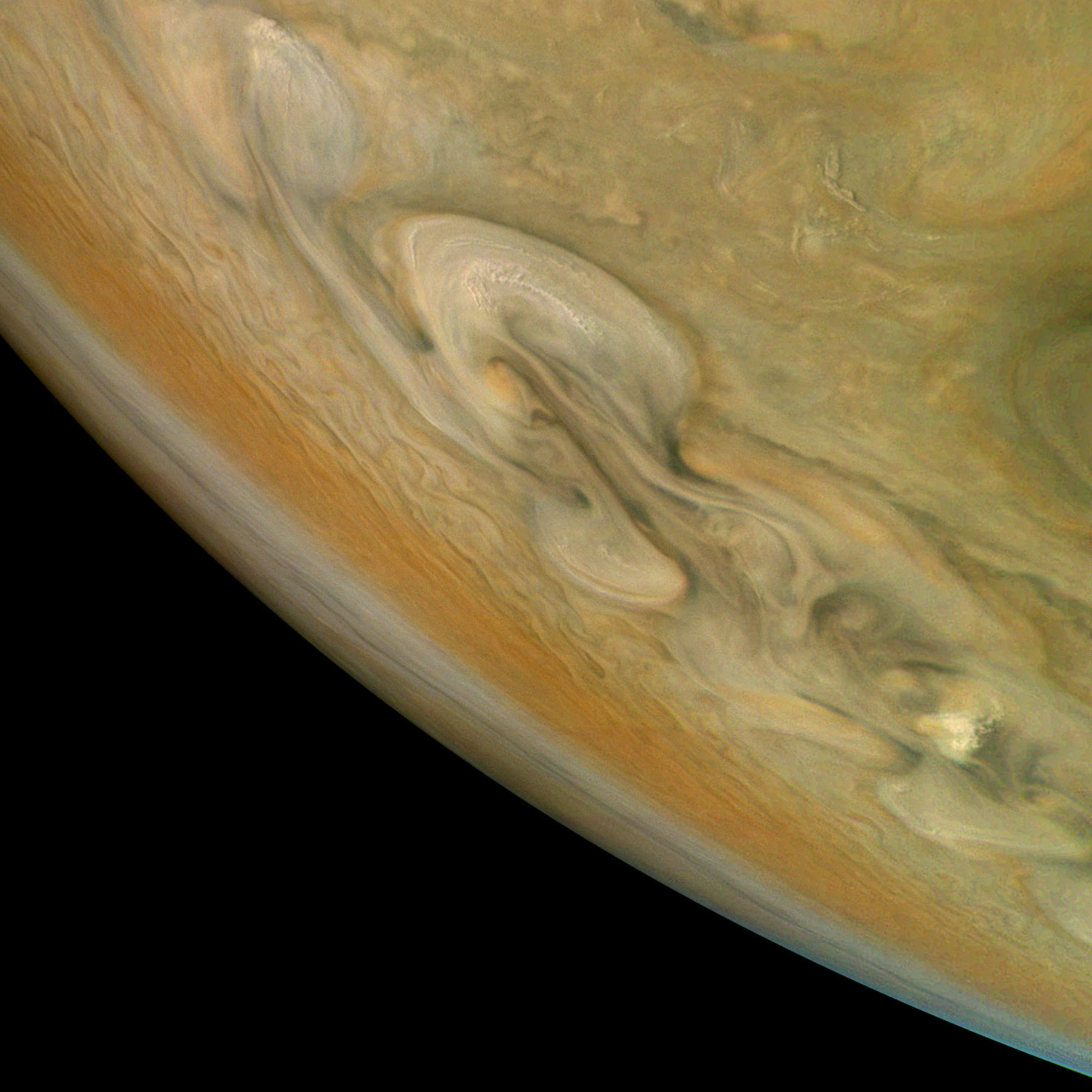

Since its arrival in orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016, the Juno spacecraft has revealed insights about the planet’s atmospheric structure, including activity hidden beneath the famous Great Red Spot, an anticyclone that measures 10,000 miles (16,000 kilometers) across, 1.3 times the width of Earth.

“Juno found that the Great Red Spot’s roots go 50 to 100 times deeper than Earth’s oceans and are warmer at the base than they are at the top,” said Andy Ingersoll, professor of planetary science at Caltech and a Juno co-investigator, in a press release announcing the latest findings in December. “Winds are associated with differences in temperature, and the warmth of the spot’s base explains the ferocious winds we see at the top of the atmosphere.”

Juno is heading for its next science pass over Jupiter’s cloud tops Feb. 7.

The spacecraft’s primary survey of Jupiter will end in July with the completion of its 14th perijove since arrival. That encounter will be the 12th close-up flyby the probe will conduct in full science mode.

Scientists plan to propose extending Juno’s mission at Jupiter beyond July, and NASA will formally decide in the coming months whether to approve additional funding to continue operating the spacecraft.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.