As divisions between them widen on Earth, space must be where countries show they can work together for a common good, France’s best-known astronaut has said in a powerful plea for international cooperation beyond the final frontier.

“From up there, the Earth seems so small, so tiny, so … the same,” said Thomas Pesquet, who spent 196 days, 17 hours and 49 minutes in space on the 50th and 51st expeditions to the International Space Station (ISS), returning in June last year.

“There are no borders. Even your own country – it’s impossible to make out where France ends, and Germany begins. You just realise, very strongly, how much we all share the same problems, how much we are, all of us, almost identical.”

Pesquet, who arrived on the ISS six months after his friend, Britain’s Tim Peake, left it, said the joint project between the US, Russian, Japanese, Canadian and European space agencies was a potent symbol of how countries can cooperate above the Earth even as below, interests diverge and tensions mount.

“Today no single country can go into space on its own,” he said. “The days when even the US could do that are long gone. And of course, up there, it’s very clear: you can only work together. You may have different views, but you have to get along. You have to make it work, every day, because you’re on the same spaceship.”

Pesquet, 39, said his spell in space – which made him so famous in France that a semi-serious campaign was launched for him to enter the presidential race – had brought home to him the urgent need for more, not less, international cooperation in the face of the planet’s “extraordinary fragility”.

Known as the overview effect, the experience of observing from 250 miles up the reality of Earth in the vastness of space has long been known to produce a cognitive shift in some astronauts. It transformed Pesquet into a militant environmentalist.

“I was already concerned about climate change and global warming,” he said, “but in a general way, like everyone else. But it’s happening on such a vast scale that from close up, it’s hard for us to grasp. In space, you take this huge step back. You experience it, fully. That really changes something.”

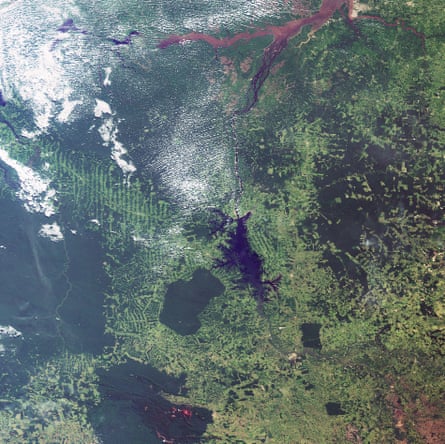

Throughout his entire half-year stay, Pesquet said, he had been unable to take a clear picture of Beijing. “You see the air pollution: it’s right there,” he said. “You see the river and sea pollution. You see the clear-cutting in the Amazon. You see how much smaller South America’s glaciers are than they were a few years ago.”

Viewed from orbit, what Pesquet called our “tiny, fragile planet, this delicate band of atmosphere that holds all of life, with nothing else all around it for billions of light years” prompted an obvious if startling comparison.

“The Earth is actually just a big spaceship, with a very, very big crew,” he said. “It really has to travel sensibly, be maintained and looked after properly, or its voyage is going to come to an end. That’s how it felt to me. That was my experience.”

The obvious need for international cooperation – despite “frictions” created, for example, by Britain’s vote to leave the EU, Russia’s annexation of Crimea and Donald Trump’s decision to pull the US out of the Paris accords, which Pesquet has publicly dubbed irresponsible – has made high-profile projects in which countries “work visibly together” all the more important, Pesquet said.

While he regrets the Brexit vote, Pesquet, who was in London to take part in an embassy event marking France’s Night of Ideas, said he did not necessarily expect it to have a major impact on the Britain’s space programme beyond UK involvement in EU-run projects such as the Galileo GPS programme (whose back-up security monitoring centre, it was announced this month, is to be relocated to Spain).

The European Space Agency is not an EU body and Britain, Pesquet said, should continue to play its part. “I certainly hope so,” he said. “As things stand, Europe has always been a relatively small player in space – Japan has a bigger stake in the ISS on its own than all of Europe.”

International space strategy over the coming years, he said, would aim to “open the door” for commercial operators, such as SpaceX’s Elon Musk and Virgin’s Richard Branson, to start operating in “near space”, while the professional agency astronauts push further into “deep space”.

The primary objective would be to send a smaller ISS into an elliptical orbit round the moon. “The moon is the focus for now, not Mars,” Pesquet said. “It’s a sensible, immediate step. We can explore and research. Test the technology three days from Earth, rather than 300.”

But whatever happens, the voices of the astronauts will be important, he said. Like Peake, who gained a big UK Twitter following during his ISS mission, Pesquet was huge on social media in France (“Much bigger than Tim,” he grinned. “You should write that. At one point I had five million followers on Facebook.”)

He lists the benefits of space exploration: modern navigation, communications, satellite and weather forecasting technologies are all by-products of man’s journeys into space. Of the 50 variables scientists use to monitor the Earth’s atmosphere and climate, more than half can only be measured from space; there is vital scientific research, notably in medicine, that can only be done in space.

In the past, the job of astronaut was largely scientific. “It’s about a lot more than that now,” said Pesquet. “It’s about teaching, demonstrating what people, and countries, can achieve when they really work together.”