Even though the “Great American Eclipse” is now many months behind us, we are still learning new things about how the passage of the Moon’s shadow affected our atmosphere.

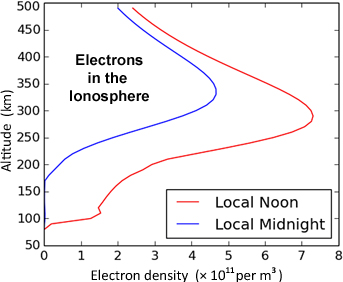

Earth scientists are particularly interested in studying the electrified layers situated 80 to 1,000 km (50 to 600 miles) above the ground, known as the ionosphere. It experienced a drastic shock as the Moon’s umbra came along and briefly shut off its one source of energy: the Sun.

Ultraviolet light from the Sun is what breaks apart molecules in the outermost layer of Earth’s atmosphere. Even though these molecules are few and far between at such high altitudes, when they’re ionized they have measurable effects, such as bouncing radio waves back to Earth. (We wouldn’t have radio reception if not for the ionosphere.) Yet during nighttime, without the Sun’s energy input, some layers of the ionosphere disappear altogether.

Dieter Bilitza et al / Journal of Geodesy (2011)

During last summer’s solar spectacular, for the very first time, the effect of the change in sunlight, in the form of ionospheric bow waves, was observed. This phenomenon had long been suspected but never actually observed.

While total solar eclipses are far from unique celestial events — occurring on average about once every 18 months somewhere on Earth — last August’s coast-to-coast totality path across the contiguous U.S. was the first such circumstance since 1918. It was this unusual shadow trajectory that allowed researchers at MIT's Haystack Observatory and the University of Tromsø, Norway, to make definitive observations of eclipse-induced bow waves.

The teams made use of the U.S.-owned Global Positioning System (GPS), a constellation of satellites that can locate a receiver anywhere in the world — as well as provide accurate, high-resolution data on the total electron content of the ionosphere. Last August, during totality’s 4,000-kilometer, 91-minute trek across 14 states, researchers studied ionospheric electron content data collected by a vast network of more than 2,000 of extremely sensitive receivers in place across the nation.

The result?

The eclipse generated clear ionospheric bow waves in electron content disturbances resulting from totality, observed most clearly over the central and eastern U.S.

Bow waves are observed whenever an object shoots through a medium more quickly than waves in that medium can travel. A speedboat, for example, will build up water along its bow that moves more quickly than waves within the water can travel.

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph

Likewise, when a jet flies, it builds up invisible pressure waves in front of it. As the jet flies faster and faster, the pressure waves can’t get out of the way of each other. Eventually, when the jet reaches supersonic speeds, the waves compress together into a single bow wave. All those in a narrow path below the jet’s flight path will be able to hear the sonic boom as it passes overhead.

During the solar eclipse, it was the Moon’s shadow that moved at supersonic speeds. In an article published last December in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, Haystack’s Shunrong Zhang and his colleagues wrote:

“The eclipse shadow has a supersonic motion which [generates] atmospheric bow waves, similar to a fast-moving river boat, with waves starting in the lower atmosphere and propagating into the ionosphere. [Such] study of wave characteristics reveals complex interconnections between the Sun, Moon, and Earth's neutral atmosphere and ionosphere.”

No doubt scientists are already looking forward to repeating this fascinating experiment at the next total solar eclipse that will pass over the United States on April 8, 2024. While the Moon’s shadow will not go coast-to-coast, its 3,400-km- long path, nearly 80 km wider than 2017’s path of totality, will pass over the central and eastern U.S., from Texas to Maine.

6

6

Comments

Edward Dubois

February 3, 2018 at 9:51 am

While watching the video I noticed another phenomenon not mentioned here. The outline of the US and Canada is a light line along the coasts and within the US is the multicolored depiction of the strength of ionospheric ions or electrons, very little in Canada which I suppose was not the focus of the experiment. What I noticed was the motion of what I will call a sort of “ion shadow”, particularly noticeable next to the Florida peninsula, that moved in the same direction as the shadow of the moon but not as fast. Also of note was the distance the ion shadow was off the coast of California at the start of the video and its subsequent separation from the main mass of ion representation. What am I seeing? Why this shadow that somewhat takes the shape of the populated countryside?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

briankutscher

March 21, 2018 at 4:56 pm

The paragraph immediately above the "The Result?" subheading ends this way: "Last August, during totality’s 4,000-kilometer, 91-minute trek across 14 states, researchers studied ionospheric electron content data collected by a vast network of more than 2,000 of extremely sensitive receivers in place across the nation."

The data was collected using GPS sensors in the U.S. Hence there is no data for Canada. That's how I would interpret the "missing data" in Canada.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

AB

February 14, 2018 at 11:01 pm

Fascinating! I was there, too 😀

Re the next one, "from Texas to Maine"... LOL, and then it stops because there is nothing outside the USA...? I am in Canada and hoping to not have to travel so far for that one. You do have readers in Canada, and we will see it here too!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

briankutscher

March 21, 2018 at 4:56 pm

The paragraph immediately above the “The Result?” subheading ends this way: “Last August, during totality’s 4,000-kilometer, 91-minute trek across 14 states, researchers studied ionospheric electron content data collected by a vast network of more than 2,000 of extremely sensitive receivers in place across the nation.”

The data was collected using GPS sensors in the U.S. Hence there is no data for Canada. That’s how I would interpret the “missing data” in Canada.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

ccc

March 7, 2018 at 11:11 am

Interesting article, about interesting observations. Reading it reminded me that, in May 1980 when Mt. St. Helens exploded, I was observing six GPS satellites continuously by means of an array of dual-band (L1 and L2) receivers distributed around the contiguous 48 states. From such observations one can infer the integral of the free-electron density along the line of sight between each receiver and each satellite. Thus I observed gravity waves in the ionosphere that had resulted from the blast wave of Mt. St. Helens’ explosion propagating upward, through the neutral atmosphere all the way to the ionosphere (above 100 km altitude), and had rippled outward horizontally through the ionosphere.

Prior to this (1980) observation I had heard of Traveling Ionospheric Disturbances (“TIDs”) but I had not known that the ionosphere could be perturbed by a tropospheric event.

-Chuck Counselman

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Milton Lachman

April 5, 2018 at 10:25 pm

It's always amusing when meteorologists stray out of their depths: e.g. calling (Compton) back-scattering of radio waves "bouncing." Furthermore, the video is evidence that the sudden lack of sunlight can't be the cause of the bow wave, as it appears well in advance of the moon's shadow. The actual mechanism must be something else, e.g. a sudden lack of solar wind, whose shadow precedes that for sunlight due to the slower speed of solar protons versus photons, so that the earth travels a greater distance along its orbit before the protons hit the ionosphere well east of where the moon's shadow is. One must also consider the tidal effect as the ionosphere will lag behind the moon much less than the oceans.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.