As fast as Ferraris are, they still can’t achieve escape velocity. For that, you need a rocket.

No, this has nothing to do with Elon Musk and SpaceX. This is a different rocket. And no, Ferrari is not getting into rocket propulsion, though I’d be happy to test one of those, should they ever decide to do that.

Let's start a little further back. The vice president and events chairman of the Ferrari Club of America’s Southwest region, Jim Bindman, does his job with an enthusiasm unmatched perhaps anywhere on this planet -- at least unmatched among car club vice presidents. A couple months ago, with Bindman’s zeal, the club was able to attend a rocket launch at Vandenberg Air Force Base. A month after that, they helped celebrate the Air Force’s 70th birthday with a car show at Edwards Air Force Base, with none other than Gen. Chuck Yeager in attendance. Now, as a fundraiser for the Navy Seal Honor Foundation the club just met at Virgin Orbit in bucolic Long Beach, California, where they held another car show of sorts.

The club had arrived en masse in 348s, 488s, F12s, FFs, GTC4 Lussos, a 330 (or maybe it was a 365), and one guy drove his magnificent F40 (all F40s are magnificent, just to clarify). That alone would have been worth seeing.

But the destination for the day’s drive was Virgin Orbit, the new and innovative rocket launch specialists with otherworldly aspirations, all of which start in a 180,000-square-foot building next to the Long Beach airport.

“If we were a minivan club, I don’t think they’d have us here,” Bindman said, once the tifosi had assembled inside Virgin Orbit’s big building.

Just to clarify, this place wasn’t Virgin Galactic. Galactic sends people into space via that very cool-looking rocket plane thing. Virgin Orbit sends satellites into space. Not people. The idea is to do it cheaply and quickly.

“Space projects are expensive,” said Will Pomerantz, VP of special projects at Virgin Orbit and our tour guide for the day. “Our mission is to take the awesomeness of space and remove the barriers to it.”

Getting to space used to require a big chunk of the GDP of only a handful of really big, relatively wealthy countries. Last year, there were 90 flights to space, Pomerantz said. The year before, there were 86. It’s still expensive.

“Raise your hand if you own your own satellite,” Pomerantz said.

The idea now, through efforts like those of Virgin Orbit, is to democratize space. If you want an entire Virgin Orbit LauncherOne rocket to yourself, it’d be $12 million to $15 million. If you share payload space with other satellites, it’s less.

One thing that helps cut cost is size – make your satellite smaller and it costs less to get it into space. While there are still satellites the size of 18-wheelers that cost millions to build, there are also satellites the size of a Coke can that cost $10,000 to build.

“We can launch hundreds of Coke-can-sized satellites,” he said.

Some can be as simple as an iPhone, though satellite geeks would probably use an android. One company did just that, launching hundreds of smart phones into space that take pictures of every part of the Earth every day. That company now owns the largest fleet of satellites in the world, or near the world.

“I would love to see Long Beach High School launch a satellite,” Pomerantz said. “When we put satellites in the hands of normal people you’re going to see lots of crazy ideas, some good, some bad.”

Virgin Orbit will launch them all (except death rays and stuff like that, those are prohibited).

The way Virgin Orbit will do it so cheaply is by eliminating the first 35,000 feet of space travel. The company’s LauncherOne rocket is slung under the left wing of a 747-400, in the space designed to ferry spare jet engines around the globe. Being a sister company of Virgin Airlines, getting a spare 747 was easy. They stripped the interior – the seats and the inflight bar are used for seating in the factory break area – and renamed their new/old jumbo jet Cosmic Girl. It’s parked on the Long Beach airport runway a block away from company headquarters.

There are many advantages to launching from an airplane at 35,000 feet. There is a lot less atmosphere up there -- and a lot less friction. You can launch anywhere on Earth, depending on whether you want a polar orbit over the poles or a geostationary orbit over the equator. You save all that heavy rocket fuel needed to get off the ground (90 percent of the weight of a rocket is fuel), and there is no waiting in line for Cape Canaveral to be available. Virgin Orbit wants to do 24 rocket launches in its first year starting this summer, with 40 or 50 a year after that.

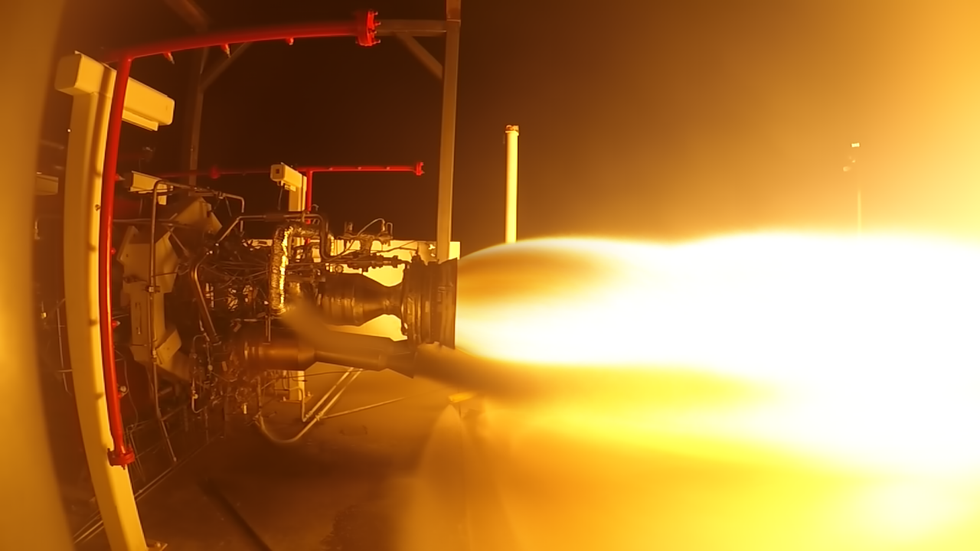

The rocket, too, is aimed at being cheap. It’s a two-stage LOX/RP-1 rocket. The LOX means liquid oxygen and the RP-1 is like kerosene. Blend them together at the right rate with “turbo pumps” and LauncherOne’s single main stage will produce 75,000 pounds of thrust.

“Rocket science is just plumbing,” Pomerantz said, only partially in jest. He says the line is meant to help demystify a field that can be extraordinarily intimidating to most people.

Burning for three minutes, the Virgin Orbit rocket reaches about Mach 25, Pomerantz said, while the Virgin Galactic rocket, which doesn’t go all the way into orbit, hits just Mach 3.5. He did not say that to tweak the noses of his colleagues at Virgin Galactic -- rocket scientists do not talk trash -- but to show the difference between spaceships and rockets, which are formidable, indeed.

The second stage makes 5,000 pounds of thrust and burns for a total of six minutes, broken up into shorter and shorter burns as it reaches its target orbit. And then there you are, in orbit, beeping happily around planet Earth for just 12 million bucks -- less if you share the ride, like Uber.

LauncherOne can push as much as 700 pounds into orbit, something about the size of a refrigerator, though more typically it’s two washing machines (those must be technical, rocket-science measures of volume).

LauncherOnes are not reusable. They are designed to fall into what rocket scientists call “Point Nemo,” the part of the vast Pacific Ocean that is farthest from any land. By the time they splash into the ocean, the biggest part is supposed to be the size of a penny. The satellites themselves must fall back to Earth within 25 years, though most will “deorbit” within five to 10 years. Most satellites are functional for just three years, after which their technology has become outdated.

There are five or six competitors aiming to do the same thing, Pomerantz said. All of them together will bring the potential of space to just about anyone.

Look for Autoweek One to be flying soon.

And with that, the tour was over and everybody filed outside to have lunch at the mobile In-N-Out burger truck that Bindman had arranged. Maybe the next satellite will be Bindman One? He has the organizational acumen for it. Then everyone got into their Ferraris and drove home, the wiser for having come.

Vehicle Model Information

ON SALE: Summer 2018

BASE PRICE: $12 million

AS TESTED PRICE: $15 million

POWERTRAIN: Two-stage LOX/RP-1-fueled rocket

OUTPUT: 75,000 pounds thrust

CURB WEIGHT: 55,000 pounds

0-60 MPH: Oh man

FUEL ECONOMY: 49,500 pounds of fuel per 22,236 miles

OPTIONS: Little green men

PROS: Fast, cheap

CONS: UFO abduction