Only a few hours after the world beheld the launch of Falcon Heavy, Elon Musk had already decided the monster rocket was too small.

“I finished looking at the side boosters, and they’re pretty big—you know, 16 stories tall, 60-foot leg span," Musk said at a press conference following the launch. "But really we need to be way bigger than that."

The Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy are both closing in on their final designs. The so-called "Block 5" update will be the last major upgrade to the rockets, one that will increase the rockets' thrust and reusability and also allow SpaceX to certify the Falcon 9 to carry crews of astronauts on the Dragon 2 spacecraft. To go "way bigger than that" will require something new.

SpaceX is banking its future on the Big Falcon Rocket, or BFR—although the original name for the rocket is a bit more colorful. And this week's big success was a boon for Musk's ever bigger dreams. “It’s given me a lot of confidence that we can make the BFR design work,” Musk says about the Falcon Heavy launch and landing of the two side boosters. In fact, Musk says SpaceX could begin short flight tests of the second stage of BFR next year.

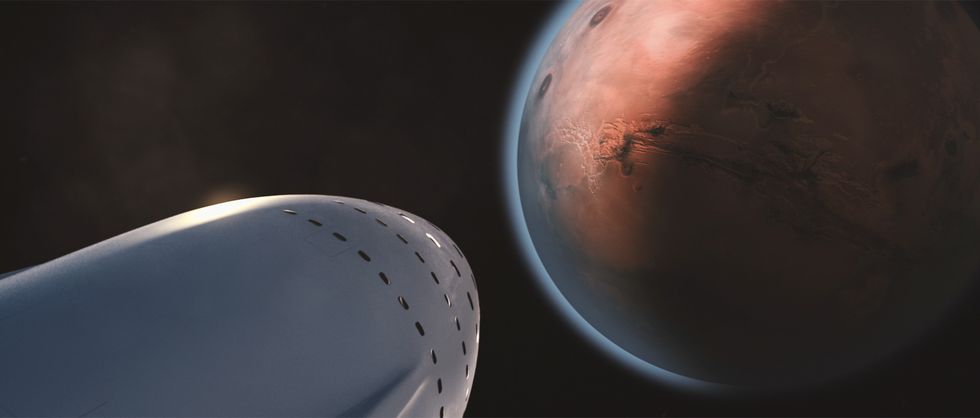

The Big Falcon Rocket will consist of a massive first-stage booster with 31 Raptor engines—a new rocket engine SpaceX began test-firing in September 2016. The second stage, also known as the Interplanetary Transport System, is a 48-meter long, 9-meter diameter spaceship that, on paper, could carry up to 100 people on flights to other planets. It's a rocket that could fulfill Musk's ultimate goal: colonizing Mars.

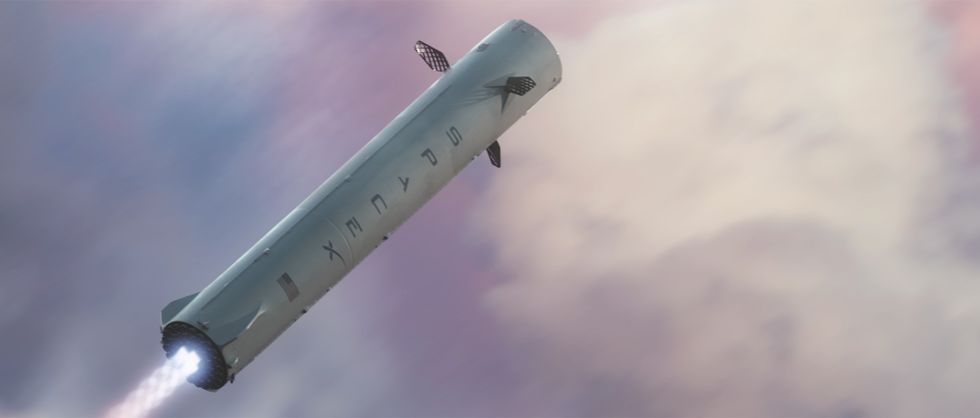

“I think we might be able to do short hopper flights with the spaceship part of BFR, maybe next year,” says Musk. "By hopper tests, I mean kind of like the beginning of the Grasshopper program for Falcon 9... it will go up several miles and come down."

The Grasshopper was a small experimental rocket SpaceX built to test vertical takeoffs and landings, a program that paved the way for Musk's company to land full-scale boosters like it did with two of the three from this week's Falcon Heavy test flight. The first flights of the BFR spaceship will be similar tests, and Musk said those flights probably would take place at a new commercial spaceport that SpaceX is building on the beaches of south Texas, just outside of Brownsville. However, Musk said it is possible the BFR hopper tests are conducted "ship to ship," potentially using two drone ships and flying the spaceship from one to the other.

Musk said the tests need to take place somewhere remote, "so if it blows up it's cool." He also said the spaceship should be capable of flying to Earth orbit itself, a requirement for the long-term plan of having the Interplanetary Transport System fly back to Earth from the moon or Mars.

These initial tests need to make sure the spaceship can hold up to intense reentry heats. "The ship part is by far the hardest. That's gonna come in from super-orbital velocities," Musk says, meaning the spaceship will be returning at incredibly high speeds from beyond Earth's orbit. He explained that some of the heating elements will scale to the eighth power on reentry.

"[We] really want to test the heat shield material, so we're going to fly up, turn around, [and] accelerate back real hard."

In addition to the spaceport in Brownsville, SpaceX is considering expanding its facilities in San Pedro, California, to accelerate work on the interplanetary spaceship, as reported by Wired. Musk hopes the Big Falcon Rocket will ultimately be capable enough to replace Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy.

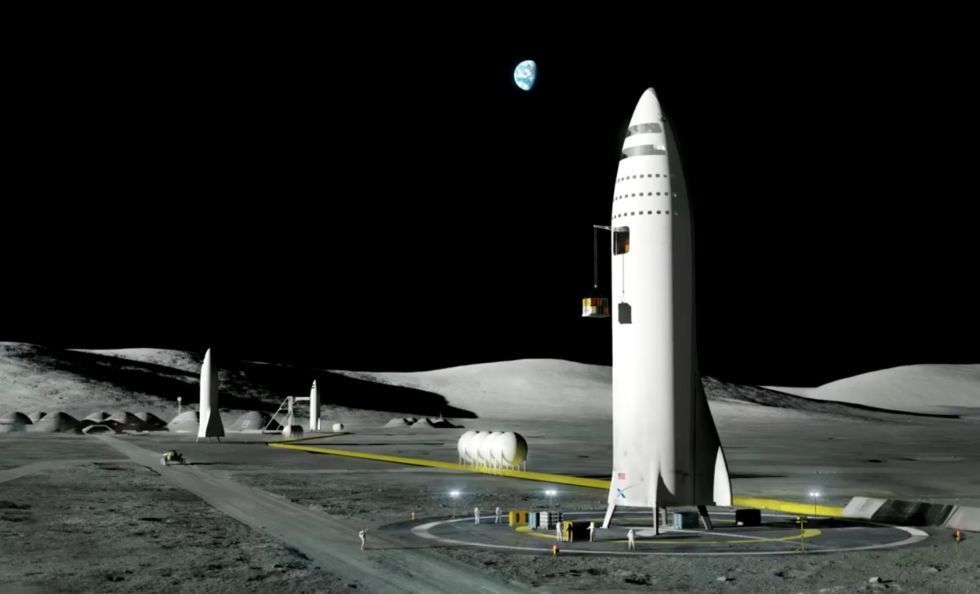

"Now that we're almost done with Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy... most of our engineering resources will be dedicated to BFR," he says. "I think it's conceivable that we do our first test flight in three or four years—full on orbital test flight of the new booster... going to the moon shortly thereafter."

That timeframe is ambitious to say the least. Falcon Heavy was announced in 2011 and took seven years to realize. The BFR is even bigger and more complex, designed to fly with four more engines than Falcon Heavy, and those engines are still in development. If SpaceX is going to fly the BFR booster and spaceship by the early 2020s, then getting started on flight tests for the Interplanetary Transport System is absolutely crucial.

"Testing the ship out is the whole tricky part," says Musk. "The booster I think—I don't want to get complacent—but I think we understand reusable boosters. Reusable spaceships that land propulsively, that's harder."

BFR is the most arduous spaceflight project SpaceX has ever attempted—an enormous booster with a second-stage spaceship that can fly a hundred people to the moon or Mars, launch commercial payloads, and even fly passengers from a city on Earth through space to land in another city as an alternative to airliners. SpaceX is going to learn a lot building BFR, probably producing some epic explosions along the way.

Whether BFR will fly in its complete configuration within three or four years is anyone's guess at this point. It's safe to say there will be unforeseen challenges and likely delays, but after witnessing Falcon Heavy, it seems that if anyone can pull off a large reusable interplanetary spaceship, its SpaceX.

Jay Bennett is the associate editor of PopularMechanics.com. He has also written for Smithsonian, Popular Science and Outside Magazine.