Will it cost a trillion dollars to send humans to Mars?

“That’s a number I’ve heard a lot,” Torrey Radcliffe, who analyzes the costs of human space exploration for the Aerospace Corporation, said at the Humans to Mars Summit today. “I’ve never seen one reach a trillion dollars.” But, he says, the big ticket price is not the right question. “That’s the reason we have the sand charts,” he says.

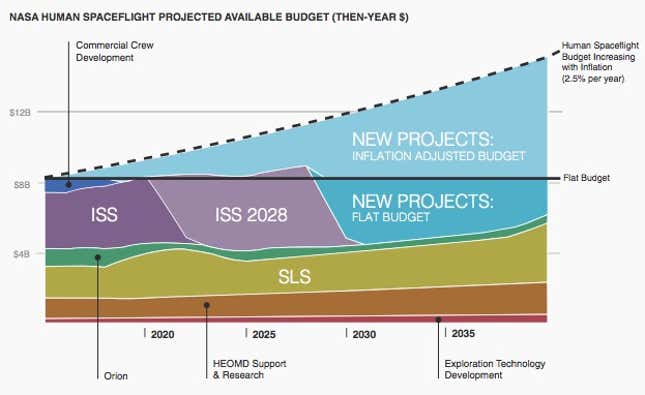

The sand chart uses area to depict the costs of developing, operating and sustaining all the stuff needed to send people into space over time. The key benchmark Radcliffe and his colleagues use for these charts is the amount of money the US government gives NASA every year for human exploration, with the assumption that it won’t go down—and might increase gradually.

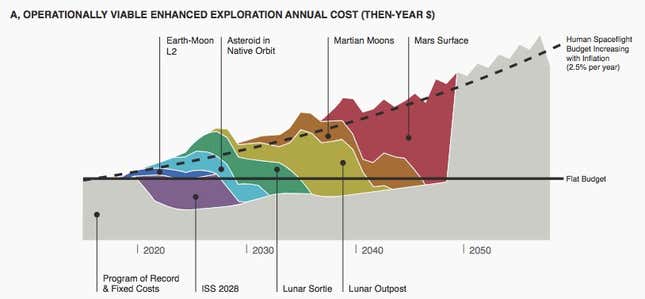

Spoiler alert for those who do want the big ticket price: To get a US mission to Mars before 2050, the program must cost less than $220 billion, according to a significant 2014 government study that Radcliffe contributed to. That’s about the same as the 2017 economic production of Uzbekistan, or less than a third of what the US government spends annually on national defense.

To understand that number, consider what the current space program looks like in a sand chart:

NASA loves its acronyms: ISS is the International Space Station, which could be phased out sometime in the next two decades; SLS is Space Launch System, an enormous rocket that could help carry hardware into deep space; HEOMD is the Human Exploration Operations Mission Directorate.

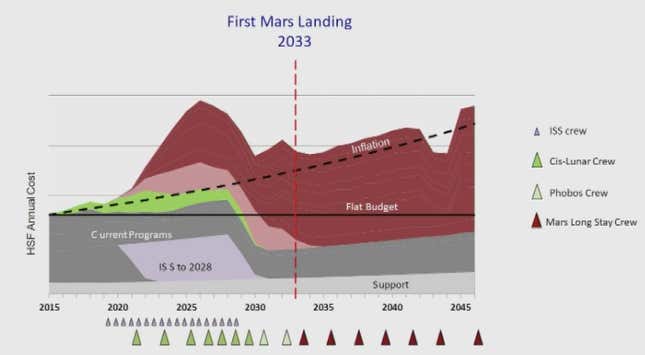

Compare that to a sand chart depicting the results of NASA trying to land on Mars as soon as 2033:

You can see that the huge up-front costs of building the infrastructure to send people on the longest voyage ever made would demand immediate budget increases that seem impossible to enact.

The only way analysts can conceive of a viable government exploration program—both affordable and sustainable—is to push a future human landing on Mars to the 2040s:

If that seems like a long wait to you, you’re not alone.

“To many engineers, students and others, if you tell someone that something is going to happen in twenty years, twenty years is never,” Josh Brost, a SpaceX executive, said at the summit. “Fifteen years is hard to be motivated. You have to be something that’s sub-a decade to get large masses of people excited about what you’re trying to accomplish.”

SpaceX, the rocket company founded by Elon Musk, is developing a new rocket to carry people to Mars, which he hopes to send on an uncrewed demonstration mission as soon as 2022, a goal even Musk admits is “aspirational.” Musk’s company is focused on Mars, but leverages the growth of commercial activity in space to help fund its broader dreams. One debate at the Summit was whether using reusable rockets will make Martian missions cheaper up front. SpaceX’s engineers believe reusability is the key, but many in the government space program remain skeptical.

Such debates are nothing new. As the National Research Council’s 2014 analysis of space exploration noted, twenty years before the first humans landed on the moon, “it would have been difficult to anticipate the technological progress in many area—from computing to guided missile technology—that would enable Apollo. Many, perhaps most, of those technology advances resulted from research outside NASA. The architectures imagined for travel to the Moon by visionaries of the late 1940s bore little resemblance to the path ultimately followed.”