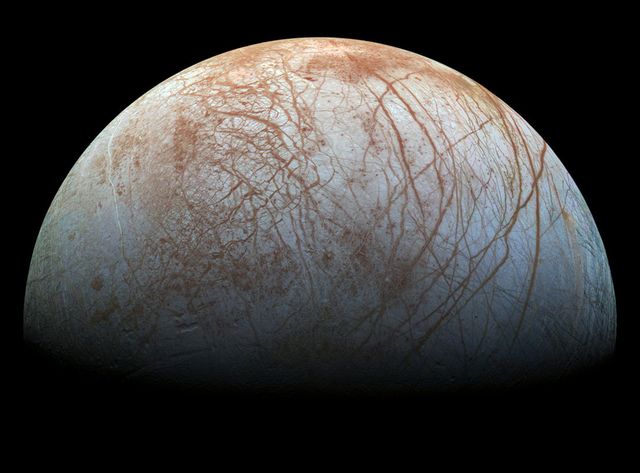

- Jupiter's moon Europa probably has a vast ocean under its surface, and it may blast plumes of water out into space.

- It turns out that Galileo, a probe that visited Jupiter in the 1990s, probably flew through one of those plumes.

- The finding backs up the idea that Europa has liquid water and enough energy to possibly support alien life.

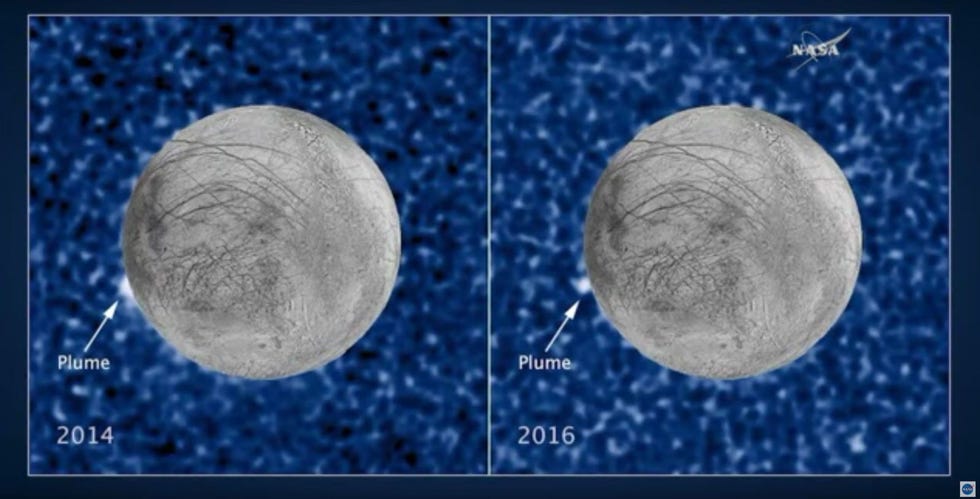

About a year and a half ago, astronomers reviewing Hubble Space Telescope observations caught a blurry glimpse of what they believed were plumes of water erupting from Jupiter's icy moon Europa. The observations support the idea that Europa has a vast subterranean ocean buried beneath about 10 km of icy crust—an ocean with more water than all the oceans of Earth combined. The plumes would not only confirm the presence of water, but also indicate that significant heat and energy from the mighty gravity of Jupiter could be churning the interior of Europa.

To try to confirm the existence of plumes on Europa, researchers went back to data from the last spacecraft to get close to the moon: Galileo. Sure enough, evidence of plumes was right there in the records from that mission, sitting idle for more than 20 years.

In fact, a paper published today in Nature Astronomy suggests that Galileo actually flew through a water plume in 1997 as low as about 206 km in altitude, right where Hubble spotted the supposed plumes in late 2016. With warm waters below the surface and enough energy to eject geysers out into space, microbial life on Europa is looking more possible than ever.

Here's what you need to know:

What are the plumes?

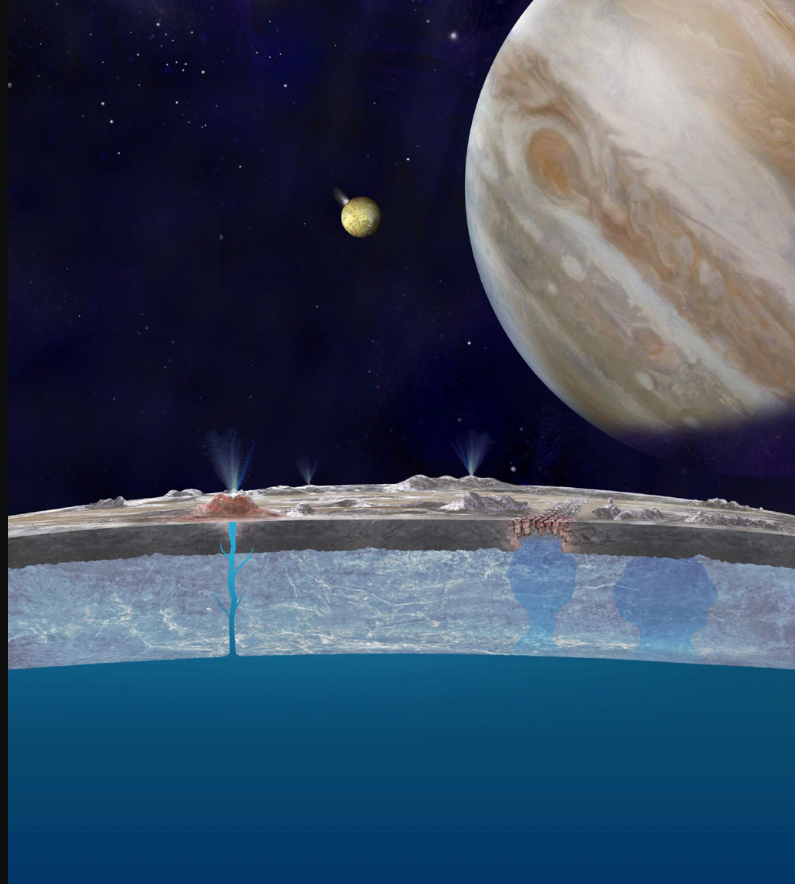

The plumes are, essentially, areas where liquid water from the ocean below Europa's icy crust erupts from the surface and vents out into space—something like geysers on Earth. The presence of liquid water on Europa suggests a warm and active world, and plumes at the surface reinforce the idea that Europa is a dynamic world with plenty of energy. At almost 500 million miles from the sun, the heat and energy primarily come from tidal interactions between Europa and Jupiter, similar to Earth's moon tugging on the oceans of our planet.

But there's been some debate in the astronomy community as to whether Europa actually has any plume activity. The previous observations from the Hubble Space Telescope were made at the very fringes of the telescope's capability, leaving room for doubt. Evidence closer to the moon itself was needed.

"After seeing those Hubble images of potential plumes, we were inspired to find out if the old Galileo data set had any potential evidence that would be linked to plumes," lead author Xianzhe Jia of the University of Michigan says.

How did Galileo detect plumes in 1997?

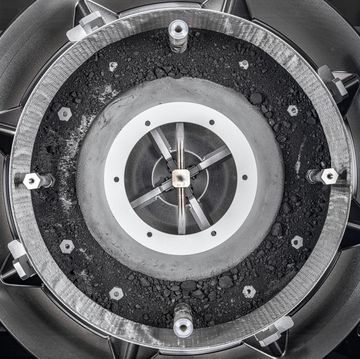

The Galileo space probe didn't see the actual plumes. But on December 16, 1997, Galileo moved in for a low approach over Europa, dipping as low as 206 km (128 miles) above the surface. At about 400 km (250 miles), the magnetometer on the craft started picking up shifts in the magnetic field, peaking at closest approach. The craft was flying near the equator, over the exact region where Hubble spotted plumes, and the evidence suggests that the spacecraft might have actually passed through part of the plume, which measured roughly 1,000 kilometers thick.

"Both the magnetic field magnitude and the plasma density were exceptionally high upstream of Europa," the paper says. "About 1 min before closest approach, the magnetic field changed by hundreds of nT [nanotesla] in 16 s. It is this short timescale fluctuation appearing in the context of slower background fluctuations that we regard as marking the passage through a plume of the characteristics extracted from Hubble images."

However, there is not more evidence from the encounter because the high gain antenna on Galileo failed to deploy earlier in the mission. Delays to the Galileo launch caused by the Challenger disaster in 1986 mean the spacecraft sat in storage for a few years, and the lubricant needed to efficiently deploy the antenna dissolved. The umbrella-shaped antenna would have provided the most high fidelity data, including imaging, but the Galileo team had to be judicious when using the instruments on the craft, which could carry only 114 MB of data.

"If they had better data quality, they might be able to give us further insight into the plume and its properties," Jia says.

How did they know the magnetometer was detecting plumes?

The first published evidence of plumes on another world came in 2013, but it was not Europa where these space geysers were spotted first. A full 10 years after Galileo had crashed into Jupiter—in part to protect Europa's precious ocean from possible contamination by Earth bacteria—scientists working on the Cassini team described plumes coming from Enceladus, a moon orbiting Saturn.

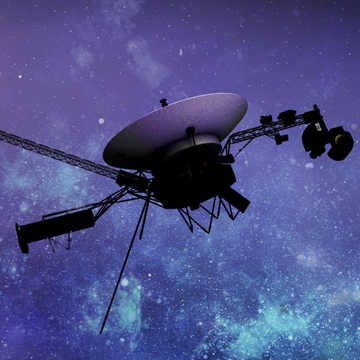

The Cassini spacecraft arrived at Saturn in 2004 and spent a spectacular 13 years at studying the planet and its moons. Seemingly sleepy little Enceladus—a moon just 16 percent the size of Europa—had perplexed Voyager mission scientists with its youthful appearance, and so they planned a flyby to figure out why it had almost no craters on its surface.

In 2005, they got a clue as to the reason—geysers of water reaching 100 miles high that indicated an ocean below the crust of ice. That ocean is likely replenishing the surface with fresh ice, removing signs of craters. Continuous measurements—including a flyby that took the Cassini probe inside the path of the plume water—gave scientists a lab to examine all the ways these geysers affect measurements of other worlds.

"They had much more comprehensive measurements in the plume," Jia says. "Here, we don’t have that."

Readings from the Cassini spacecraft at Enceladus helped scientists determine how the plumes there affect magnetic field readings. So now, looking back at Galileo data, the magnetic mark of watery plumes has become clear.

Where else are there plumes?

Plumes have been observed on Earth, Enceladus, and Europa, but they could be even more common than that. The Voyager 2 spacecraft also spotted plume-like activity on Triton, the largest moon of Neptune, in 1989, making Triton's plumes technically the first discovered—but least studied.

There's also some evidence for plumes at Pluto. Like Triton, the observations are hard to follow up on. Researchers looked for plumes at three other Saturnian moons—Rhea, Tethys, and Dione—but found nothing. Saturn's moon Titan, Jupiter's moon Ganymede, and Uranus' moon Miranda all have regions consistent with cryovolcanic activity, though it hasn't been directly detected.

What's next for Europa?

Sometime between 2022 and 2025, NASA will launch the Europa Clipper spacecraft that will make 45 flybys of the moon. The exact timing of the mission depends on which rocket the spacecraft launches on, but right now NASA is hoping to use the Space Launch System—a heavy-lift rocket currently in development that could fling Europa Clipper to Jupiter in just a few years. The mission is receiving significant support from Texas congressman John Culberson (who accidentally broke the news of Galileo detecting plumes in a congressional committee hearing).

In addition, the European Space Agency will launch the Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer mission in the next. Though it will only fly by Europa twice, instead concentrating on Jupiter's two largest moons Ganymede and Callisto, the craft could provide valuable follow-ups to Europa Clipper's findings.

Either of those craft could provide detect, high-resolution evidence of the plumes at Europa. While the plumes are not 100 percent confirmed as of now, Jia says the Galileo evidence makes a compelling case that there are water plumes at Europa. "I think the plume interpretation is the most plausible one we can come up with."

Where there is water and energy, there very well may be life.