Shooting stars streak through the night sky above Florida’s Space Coast as the Perseid meteor shower approaches its peak. Mars glows red in the predawn hours, hovering over the crowds of onlookers. But the people gathered here at Kennedy Space Center have not come to view these astronomical phenomena. They have come to witness one of the largest rockets in the world send a spacecraft to the sun.

On the launch pad at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, the 30-story-tall Delta IV Heavy is already loaded with 460,000 gallons of fuel. An ominous warning about safety liability blares over the loudspeaker. The $1.5 billion Parker Solar Probe sits atop the rocket, ready for its 3:31 a.m. liftoff.

In the minutes before the building-sized vehicle attempts to break the grip of gravity, the crowd goes silent. Then suddenly the countdown begins over the loudspeakers. Before the clock hits zero, a bright orange blaze engulfs the lower half of the rocket—a quirk of its RS-68A engines firing up—mimicking the sun itself and illuminating the surrounding area.

A wave of plumes rolls outward from the launch pad as the huge Delta IV Heavy lifts off for the tenth time ever. It takes a few moments for the sound waves to reach the crowd, roaring through the coastline and shaking the ground beneath us. In a matter of seconds, the rocket is piercing through the sky, accelerating its historic payload to a rendezvous with the sun as cheers erupt from the spectators.

Parker Solar Probe is on its way to discoveries that could answer some of the biggest questions in astronomy and physics, but the future of space exploration also hinges on the rocket that carried the craft, and the fate of the company that built that rocket—United Launch Alliance.

A Launch for the History Books

An astonished look takes over 91-year-old Eugene Parker’s face. The heavy-lift rocket's payload is Parker's namesake, a probe built to fly closer to the sun than any before it. Its mission: To investigate solar wind and study extreme particle physics.

But shortly after the thrill of liftoff, concerned murmurs spread throughout the space center. The third stage of the launch vehicle fails to signal a successful separation from the spacecraft. The mood turns pensive. The faces of the mission team members grow concerned on the livestream. Then everyone breathes a sigh of relief when it becomes clear the telemetry data was simply delayed, and the spacecraft had successfully separated as planned. A second round of applause rolls across Kennedy Space Center.

The Parker Solar Probe has begun a journey to fly within 4 million miles of the sun’s surface, into the solar corona, a five-million-mile-thick superheated atmosphere of charged particles. From the corona, these particles collectively stream out into space as solar wind.

It was Eugene Parker who theorized the existence of solar wind, a then-controversial idea that space was not a completely empty vacuum, but rather a theater of energetic particles flowing from our host star. Parker, who is the first living human to have a NASA spacecraft named for him, first published the his theory in 1958 to significant scorn from peers in the astrophysics community.

A 31-year old professor at the University of Chicago at the time, Parker would only have to wait four years until NASA’s Mariner 2 spacecraft detected particles in space, validating his work. Early Sunday morning, 60 years after Parker published his groundbreaking paper, he joined NASA on the Space Coast to witness not only a grand culmination of his life’s work, but also his first rocket launch. Parker said that in his day, rockets only worked about half the time, but he’d bet $10 that ULA’s heavy launcher would go off without a hitch.

Parker would have won his bet. The Solar Probe is far from the first high priority science mission to be successfully launched by United Launch Alliance. The question now for the Centennial, Colorado-based rocket company is how to adapt to emerging competition from companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin, billionaire-funded startups manufacturing cheaper, reusable vehicles—and gobbling up market share as they go.

A Veteran Rocket Company Looks to the Future

For a better part of the last decade, United Launch Alliance was the primary launcher for the U.S military—the most lucrative client for aerospace contractors. In 2014, ULA launched 10 national security missions. This year, with four months left in 2018, it has only flown a pair of them. SpaceX has dramatically altered the playing field with its Falcon 9, the most launched rocket of 2017, used to competitively bid for military contracts.

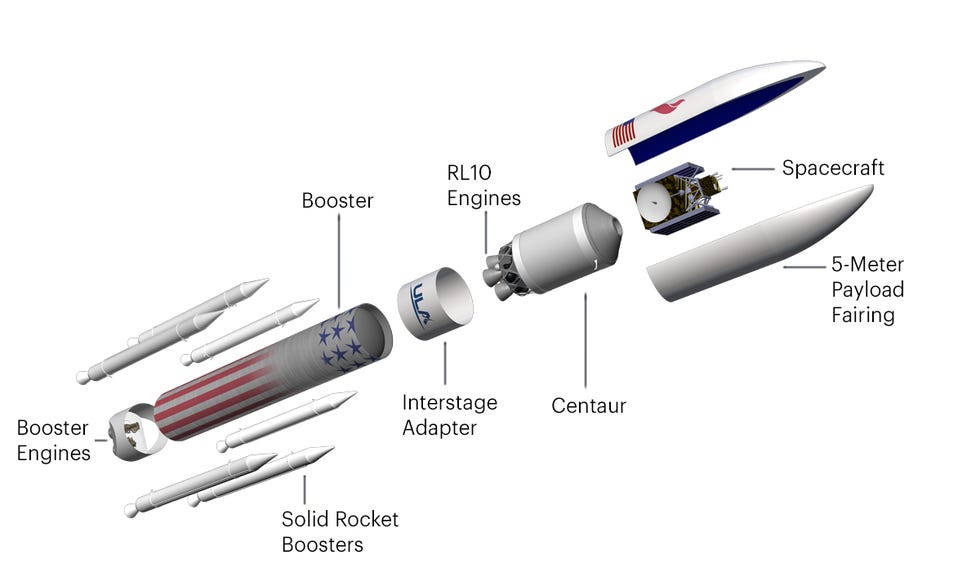

Today, Air Force contracts that were once a shoo-in for ULA are starting to go to SpaceX. NASA is flying high priority missions on SpaceX’s rockets now, too. For this new arena of competition, ULA is building a new workhorse rocket—a reusable one. In 2014, the company began development on the Vulcan, a rocket with recoverable first-stage engines that is expected to eventually replace the fleet of Atlas and Delta rockets.

ULA believes that recovering and reusing just the engines is the most sustainable path to competitive pricing while maintaining reliability, claiming that the engines account for most of a booster’s cost. The company is considering engines built by both Blue Origin and Aerojet Rocketdyne to power the first stage of Vulcan, but it has yet to make an official decision. After a launch, the Vulcan’s pair of booster engines would shut down and detach from the first stage to be caught in mid-air by a helicopter—technology that NASA is helping to fund.

Will recovering just the engines make a significant impact? According to ULA, the Vulcan can be strapped with up to six extra solid rocket boosters to reach up to 3.8 million pounds of thrust, outperforming even the Delta IV Heavy while flying for about a third of the cost. With Delta IV Heavy’s $350 million price tag up against a (fully recoverable) $90 million Falcon Heavy, Vulcan begins to look like a solid option in an industry where the days of expendable rockets are limited.

ULA will need to contend not only with the Falcon fleet of rockets, but also with New Glenn, being built by Blue Origin, and the new Omega rocket from Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems (formerly Orbital ATK). ULA's experience, reliability, and modular designs could give it an edge, but it all comes down to Vulcan.

Keeping the Most Important Spacecraft

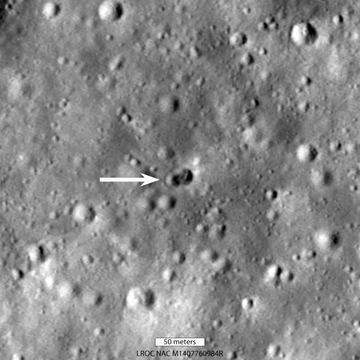

Now that the 1,424-pound Parker Solar Probe is far past lunar orbit, on its way to an October flyby of Venus, United Launch Alliance can boast 129 consecutive successful launches since its founding in 2006. The company, an outfit formed by veteran aerospace manufacturers Boeing and Lockheed Martin, also adds to a legacy of storied missions launched for NASA.

“My reaction was shear awe,” says Tory Bruno, president and CEO of United Launch Alliance. “Four hundred personal launches later, the physics defying wonder of blasting a 30-story building into space still gives me goosebumps.”

Bruno says he is looking forward to upcoming ULA launches, including another Delta IV Heavy launch for the NRO later this year and the final Delta II launch, carrying NASA’s ICESat 2 in September, “an important science mission studying polar ice.”

“I am also looking forward to Mars 2020—our 19th trip to the Red Planet.”

Friday afternoon, the day before Parker Solar Probe was initially scheduled to launch, workers and reporters gather at Launch Complex 37B to witness the Delta IV Heavy separate from its service tower. A trio of massive orange boosters tower over the pad at 233 feet. In the pond below, a hungry alligator surfaces to remind everyone that much of Cape Canaveral is still a wildlife preserve.

ULA chief Tory Bruno sports a black company-branded cowboy hard hat as he walks up a path to the rocket. He climbs to an upper-level of the service tower, and it begins to slowly move back from the rocket. The Delta IV Heavy is so massive that rather than rolling it out of a building, ULA drives the building away from the rocket.

Just a few miles down the road, four newly-assigned Commercial Crew astronauts are at work training on Boeing’s Starliner crew capsule. Astronaut Chris Ferguson, the commander of the final space shuttle mission, says the race is on to return human spaceflight to American soil. In Boeing’s corner is ULA’s Atlas V rocket, which is slated to launch the Starliner and its crew next year. But SpaceX and its Crew Dragon might beat ULA and Boeing to the punch.

ULA chief Bruno peers over the historic launch pad, the site of Apollo 5, as the tower backs away and the orange paint of the monumental rocket catches the light of the evening sun. The sun may be setting on the Delta IV, but the man in the cowboy hat is determined to make sure it doesn’t set on ULA.