Renowned astronomer Galileo Galilei has been lauded for centuries for his courageous principled stance against the Catholic Church. He argued in favor of the Earth moving around the Sun, rather than vice versa, in direct contradiction to church teachings at the time. But a long-lost letter has been discovered at the Royal Society in London indicating that Galileo tried to soften his initial claims to avoid the church's wrath.

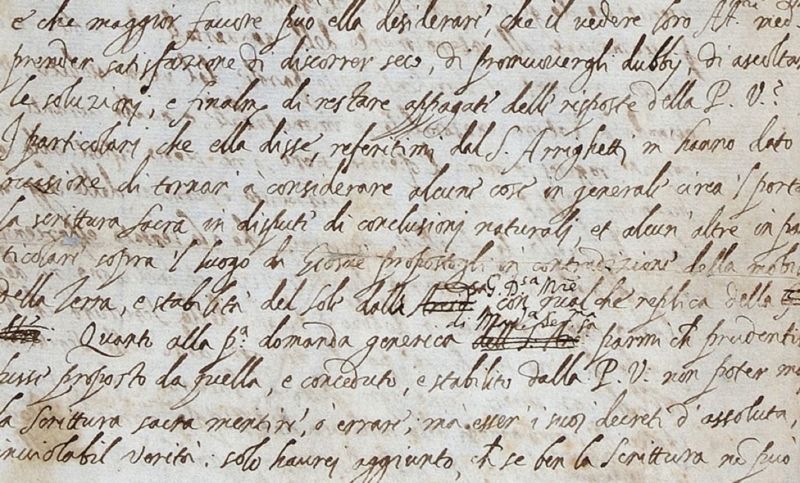

In August, Salvatore Ricciardo, a postdoc in science history at the University of Bergamo in Italy, visited London and searched various British libraries for any handwritten comments on Galileo's works. He was idly flipping through a catalogue at the Royal Society when he came across the letter Galileo wrote to a friend in 1613, outlining his arguments. According to Nature, which first reported the unexpected find, the letter “provides the strongest evidence yet that, at the start of his battle with the religious authorities, Galileo actively engaged in damage control and tried to spread a toned-down version of his claims.”

“I thought, ‘I can’t believe that I have discovered the letter that virtually all Galileo scholars thought to be hopelessly lost,’” Ricciardo told Nature. “It seemed even more incredible because the letter was not in an obscure library, but in the Royal Society library.”

Oh more than moon

To fully understand the significance of this discovery, one has to go back to Claudius Ptolemy around 150 CE, who was the first to synthesize the work of Greek astronomers into a theoretical model for the motions of the Sun, Moon, and planets—all that made up the observable universe at the time. In his Almagest treatise, Ptolemy suggested the Earth was fixed, positioned at the very center of closed, spherical space, with nothing beyond it. A set of nested spheres surrounded the Earth, each an orbit for a planet, the Sun, the Moon, or the stars.

“The aesthetics [of the Ptolemaic model] meshed nicely with the prevailing Christian theology of that era.”

Everyone loved the Ptolemaic model, even if it proved an imperfect calendar. It was so clean and symmetrical—positively divine. That’s why it was the dominant model for 14 centuries. The aesthetics meshed nicely with the prevailing Christian theology of that era. Everything on Earth below the Moon was tainted by original sin, while the celestial orbits above the moon were pure and holy, filled with a divine “music of the spheres.” It became the fashion for poet-courtiers, like John Donne (a personal favorite), to praise their mistresses as being “more than Moon” and dismiss “dull sublunary lovers’ love” as inferior and base. And it provided a rationale for maintaining the social hierarchy. Upset the order of this “Great Chain of Being” and the result would be unfettered chaos.

Everything changed in the mid-16th century when Nicolaus Copernicus published De Revolutionibus, calling for a radical new cosmological model that placed the Sun at the center of the universe, with the other planets orbiting around it. His calculations nailed the order of the six known planets at the time, and he correctly concluded that it was the Earth’s rotation that accounted for the changing positions of the stars at night. As for planets moving in apparent retrograde motion, he concluded this was because we observe them from a moving Earth.

Frankly, the book didn’t immediately cause much of a stir outside rarefied astronomical circles, perhaps because it was a massive tome brimming with tiresome mathematics. It didn’t make the list of the Roman church’s banned books until 1616. That’s when it was pulled from circulation pending “correction” to reflect that its audacious claims were “just a theory”—an argument all too familiar today with regard to evolution and creationism.

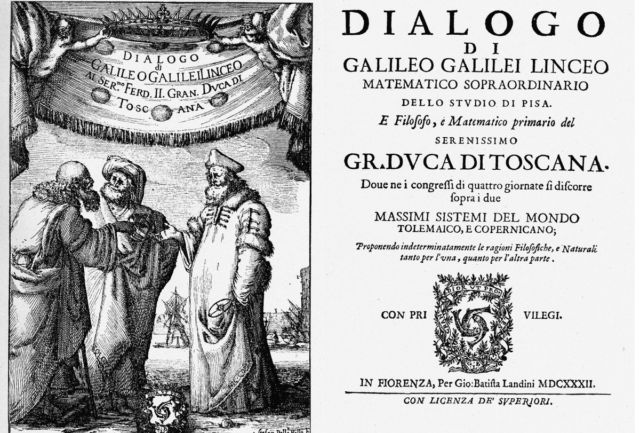

Then Galileo came along with his handy telescope (a recent invention), and his observations clearly supported the Copernican worldview. The church started taking notice, because Galileo openly espoused the Copernican system in his papers and his personal correspondence. Things came to a head in 1632 when he published the “Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems.” It wasn’t just the science that raised eyebrows. He also had the audacity to question key biblical passages typically offered in support of the Ptolemaic cosmology, insisting that the Bible is for teaching people how to get to heaven, not a scientific treatise for how the heavens move.

The Catholic Church had had enough, and Galileo found himself facing the Inquisition, forced to his knees to officially renounce his “belief” in the Copernican worldview. He was convicted of “vehement suspicion of heresy” anyway, and lived his last nine years under house arrest. He wasn’t officially pardoned by the Vatican until 1992.

Hiding in plain sight

That’s the story as it’s traditionally told. So what has changed? At issue is Galileo’s 1613 letter to mathematician Benedetto Castelli at the University of Pisa. It’s the first known instance when Galileo argued in favor of the Copernican model and that scientific observations should supersede church teaching in regards to astronomy. That letter was copied and circulated widely (a common practice in the 1600s), and a copy found its way into the hands of a tattle-tale Dominican friar named Niccolò Lorini. Aghast at the heretical implications, Lorini forwarded the letter to the Inquisition in Rome on February 7, 1615. It’s currently housed in the Vatican Secret Archives.

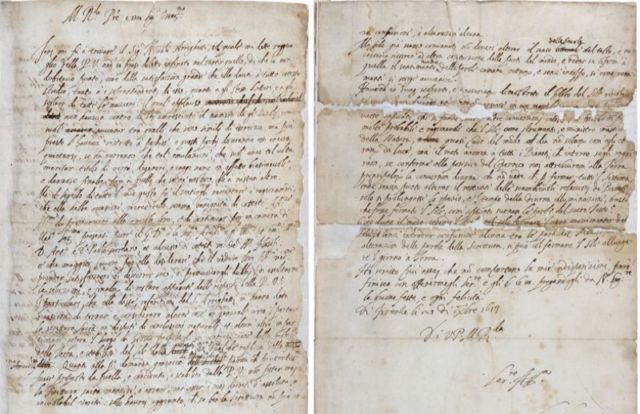

Here’s where things get complicated. Galileo asked Castelli to return his original 1613 letter to him. He then wrote to a Roman cleric friend, Piero Dini, on February 16, 1615, claiming that Lorini (in “wickedness and ignorance”) had doctored the copy of the letter forwarded to the Inquisition to make Galileo seem guilty of heresy. He enclosed a different version of the Castelli letter, with notably less inflammatory language, claiming it was the correct version.

Historians were unsure which of the two versions was correct, since the original was deemed lost—until Ricciardo stumbled across it hiding in plain sight in the Royal Society archives. According to Ricciardo, the catalog listed the date of the letter as October 21, 1613, but the actual letter is dated December 21, 1613. This may be why so many prior scholars had overlooked it. It’s also an unusual item for the Royal Society to have in its archives. The Society is currently trying to trace its provenance to determine how it ended up there.

The letter provides a strong piece of evidence that Galileo was the one fibbing here and deliberately modified the version he asked Dini to forward to the Inquisition, in hopes of appeasing the church’s wrath. Per Nature:

Beneath its scratchings-out and amendments, the signed copy discovered by Ricciardo shows Galileo’s original wording—and it is the same as in the Lorini copy. The changes are telling. In one case, Galileo referred to certain propositions in the Bible as “false if one goes by the literal meaning of the words.” He crossed through the word “false” and replaced it with “look different from the truth.” In another section, he changed his reference to the Scriptures “concealing” its most basic dogmas, to the weaker “veiling.”

Ricciardo and his colleagues—Franco Giudice of the University of Bergamo and science historian Michele Camerota of the University of Cagliari—conducted their own handwriting analysis. They compared individual words in the newly discovered letter with similar words in Galileo’s other writings from around the same time period. They concluded the handwriting was indeed Galileo’s.

Should we conclude from this that Galileo was not the scientific hero we've long thought him to be? Surely not. The changes are minor, mostly regarding his statements about the Bible, not his scientific analysis. It’s difficult for us to conceive just how dangerous a time the 17th century was for scientists and scholars who dared to cross the Catholic Church. Galileo was fortunate not to have been burned at the stake for his claims; thousands of less-fortunate people around the world were executed for heresy over the centuries that the Inquisition existed. Who could begrudge him those last nine years of relative quiet and contemplation? This merely shows the complicated man behind the heroic stereotype—one with sufficient diplomatic skill to soften his words without diluting his science.

reader comments

268