In 1962, US president John F. Kennedy famously offered up an explanation about why NASA was setting its sights on the moon.

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do other things, not because they are easy but because they are hard,” Kennedy said, going on to suggest that Americans were pushing the limits of space exploration because the desire to discover and learn was in their nature. “We set sail on this new sea,” he said, “because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people.”

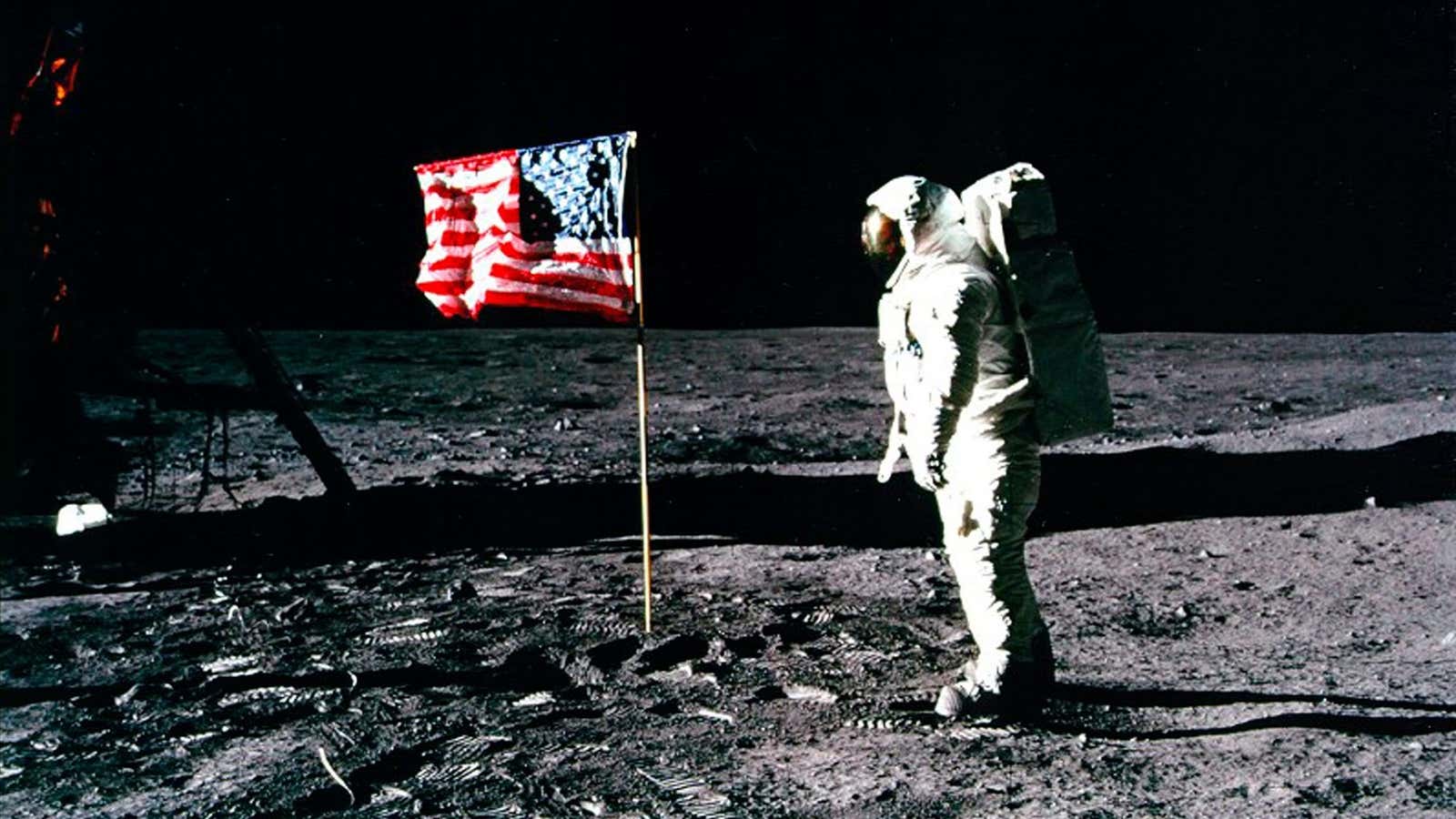

Now we know the ending: Americans did, indeed, make it to the moon, and that makes it easy to look back at the Apollo missions with rose-colored glasses. But it was very hard: An estimated 400,000 engineers played a hand in putting man on the moon. And it cost us not only billions of dollars, but the lives of three Apollo astronauts. So it makes sense that, despite Kennedy’s declaration of a nation with a united vision, a large number of Americans were skeptical of the lunar missions or outright opposed them.

Now that often-neglected piece of American history is being brought back to the forefront of cultural memory thanks to First Man, the new Neil Armstrong biopic. The movie showcases a range of objections to the moon mission, via scenes featuring protesters, doubtful newspaper headlines, and, memorably, a recitation of Gil Scott-Heron’s poem “Whitey on the Moon.”

Indeed, despite his moving words, Kennedy himself didn’t have that much faith in space exploration. In a 1962 White House meeting just a couple months after his famous moon speech, Kennedy told NASA administrator Jim Webb that he was “not that interested in space” and that the “fantastical expenditures” of the lunar program had “wrecked our budget.” Kennedy said that his main motivation to keep the lunar program going was political: In the midst of the Cold War, getting to the moon before Russia was a priority. “This is—whether we like it or not—an intense race.”

The public was not wild about NASA’s lunar program, either. In 2003, space historian Roger Launius reviewed public opinion polls about space exploration between the 1960s and 1990s, uncovering Americans’ deep skepticism of space exploration. A majority of the public was not convinced that space exploration was an important enough issue to merit funding, and that the billions being spent at NASA should instead go towards fixing other social ills. In Launius’s paper, published in the journal Space Policy, he references a 1965 poll in which more than half of respondents ranked issues like national defense, education, anti-poverty programs, and even water desalinization research as more worthy of government spending than space exploration.

In one poll from the summer of 1965, Launaius explains, a third of Americans supported cutting the space program budget, and by 1969, that had increased to 40%. Even after the moon landing, people were still skeptical:

The only point at which the opinion surveys demonstrate that more than 50 percent of the public believed Apollo was worth its expense came in 1969 at the time of the Apollo 11 lunar landing….and even then only a measly 53 percent agreed that the result justified the expense, despite the fact that the landing was perhaps the most momentous event in human history since it became the first instance in which the human race became bi-planetary.

Public opinion may still be swayed by the media and popular culture, however. Launius points to polls between 1989 and 1997 asking about people’s attitudes on manned as opposed to unmanned missions. Through most of that period, people supported unmanned missions over manned ones; this isn’t terribly surprising, given the tragic

.

But, Launius observed, public sentiment shifted towards supporting manned missions again in 1995, which, coincidentally, was the year that

Apollo 13

was released. Other movies like

Armageddon

,

Deep Impact

, and

Contact

may have helped buoy interest in manned space exploration through the late 90s and early 2000s. Now that NASA’s turned its sights towards a Mars mission, perhaps movies like

First Man—

along with films like

The Martian

and

Interstellar

—will play some role in maintaining public interest in humankind’s exploration of the universe.