Launch startup Relativity Space has won approval from the U.S. Air Force to take over a disused launch pad at Cape Canaveral for the company’s methane-fueled Terran 1 rocket, a 3D-printed launcher that could carry small satellites into orbit by the end of 2020.

Relativity announced Jan. 17 the Air Force approved the company’s plan to move in at Launch Complex 16, a long-dormant facility at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida once used by Titan and Pershing missile tests.

The agreement makes Relativity Space, “the first venture-backed company that has won approval for a site, LC-16, to start designing and building our launch facility at the Cape,” said Tim Ellis, the company’s co-founder and CEO. “We are only the fourth company after SpaceX, ULA and Blue Origin to have an operational site, so we’re joining an elite group of other launch companies out at the Cape. We’re really excited about it.”

Backed by venture capital funds and an early investment from billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban, Relativity has lofty goals of revolutionizing how rockets are built and flown, using advanced 3D printing to manufacture engines, tanks and other structures.

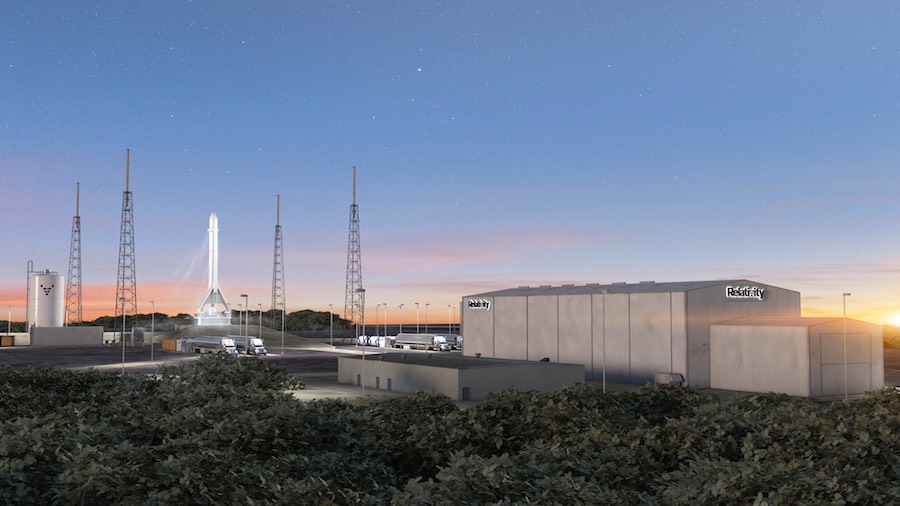

Complex 16 was last used for a launch in 1988, and is located on the historic “missile row” at Cape Canaveral, south of ULA’s Delta 4 pad and north of SpaceX’s rocket landing zone. Relativity intends to move in to the facility and build payload and rocket processing hangars, lightning masts, and propellant holding tanks, among other infrastructure to ready for the maiden flight of the Terran 1 rocket by the end of 2020.

The two-stage Terran 1 rocket, powered by Relativity’s own Aeon engines, will stand around 100 feet (33 meters) tall, and will be capable of carrying up to 2,750 pounds (1,250 kilograms) to low Earth orbit. The Terran 1’s carrying capacity to a more useful sun-synchronous orbit at an altitude of around 300 miles (500 kilometers) is roughly 2,000 pounds (900 kilograms).

Relativity expects to charge customers around $10 million per launch.

Ellis said his launch site development team met with representatives from the Air Force’s 45th Space Wing, the unit which manages operations at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, rather than pursuing a use agreement through Space Florida, a state-backed economic development agency that has inked deals to bring other aerospace companies to the Space Coast.

“That’s really important for a few reasons,” Ellis said in an interview with Spaceflight Now. “First and foremost, having a direct agreement means that there is a clear path, as we build the launch site and actually fly Terran 1 by the end of 2020, that then executing successful launches means we have a path toward a future exclusive agreement, which would then allow us exclusive use of this site for 20 years. Really, it’s in our hands now to deliver on actually launching.”

Spaceflight Now members can read a transcript of our full interview with Tim Ellis. Become a member today and support our coverage.

Other launch sites around Cape Canaveral are billed as multi-user facilities, where several companies could share infrastructure.

“I know some of the sites that Space Florida has are more multi-user sites where there could be more scheduling conflicts, (with) uncertainty about what kind of frequency is possible with those sites just because there may be multiple tenants,” Ellis said.

Ellis also sits on the Users’ Advisory Group of the National Space Council, a panel of industry leaders, former astronauts, politicians and retired military officers chartered to help space national space policy. The National Space Council was re-constituted last year by the Trump administration, and is chaired by Vice President Mike Pence.

Headquartered in Los Angeles, Relativity kicked off the search for a launch site soon after the company’s founding in late 2015 by Ellis and Jordan Noone, who serves as the company’s chief technology officer. Ellis and Noone, both in their late 20s, are both veterans of other commercial space companies.

Ellis is a 3D printing guru who worked for Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin space company on the BE-4 engine, which will power Blue Origin’s planned New Glenn rocket and United Launch Alliance’s next-generation Vulcan booster. Noone worked on the propulsion systems on SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft.

The Aeon engine that will power the Terran 1 rocket will be produced using fewer than 100 parts, down from the thousands of parts that go into other rocket engines. The Aeon burns a mixture of methane and liquid oxygen to produce 15,500 pounds of thrust at sea level, and nine Aeons will be clustered on the Terran 1’s first stage for a total of nearly 140,000 pounds of thrust at liftoff.

A single vacuum Aeon engine will fly on the Terran 1’s second stage.

“It’s on the order of 7 feet in diameter, 100 feet tall, it’s liquid oxygen and liquid methane, with an open expander cycle for the engine,” Ellis said. “The vacuum engine has about 21,000 pounds of thrust.”

Hotfire testing of the Aeon engine has started at NASA’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi.

The Terran 1 will contain 100 times fewer parts than traditional rockets, Relativity says, simplifying and accelerating the timeline to manufacture and assemble the vehicles with 3D printing. Eventually, the company aims build a rocket in less than 60 days, from raw materials to a flight-ready product.

“We’re not just a rocket company,” Ellis told Spaceflight Now. “Sometimes, I feel like we’re Tesla plus SpaceX put together. I feel like we really have two products. One is the rocket, and the other is this totally new process for building rockets — the factory itself.

“We have to not just figure out to get the rocket to work, but how to get 3D printing to work and reinvent a lot of the processes for what parts look like, how they’re designed, and how you qualify and test the parts, how you analyze them,” Ellis said. “What kinds of things are different now? That is just as big of an endeavor as anything else.”

Relativity named its first 3D printer Stargate, and the company says it is the largest metal 3D printer in the world. Using proprietary materials, the machine has already produced prototype propellant tanks for structural testing, and has built-in sensors and smarts to track and improve its performance. Stargate has multiple print heads perched at the ends of actuating arms to build complex components with unusual geometries, and to allow for a faster production cadence.

“We really truly are a venture-backed company in the sense that we were just two guys in a garage with absolutely nothing, and everything we’ve built has been from scratch,” he said. “After I left Blue Origin, in their 3D printing group with the BE-4, my co-founder was working on Crew Dragon at SpaceX. Seeing this dream come to light has been exciting.”

Relativity closed a $35 million funding round with venture capital firms last year, and is expected to seek more cash to complete development of the Terran 1.

“We’re always looking for opportunities to go faster, and getting to orbital flight and getting to our production cadence,” Ellis said. “We still have plenty of dry powder, but rockets certainly are expensive, and we have huge ambitions as a company, so we’re always looking to talk to more people.”

Since obtaining the fresh venture capital funding last March, Relativity’s workforce has grown from 14 employees to a team of 60.

In the search for launch sites, Relativity looked at “every single launch site in the United States,” Ellis said, including currently operating and future spaceports.

“The Cape was our first choice for the lower inclination launches from the East Coast,” Ellis said. “The reason for that is our customers are already used to launching out of the Cape, so there’s significant history, not just for the rockets themselves but also where satellite companies are used to operating. We thought that was, by far, the most convenient and prestigious location for launching those payloads.

“Also, LC-16 is specifically sized not just for Terran 1, but since our rockets are 3D-printed with no fixed tooling, that means we can change the design very quickly, so the site will also support future increases in payload capacity or other advanced features that we would add to our launch vehicle,” he said.

Ellis said the launch pedestal, parts of the old flame duct, acoustic dampening and concrete infrastructure is already in place at Launch Complex 16. Roads and electrical power are also available at the site.

While significant construction will be needed to ready the launch complex for operations, the infrastructure already in place gives Relativity a head start. Ellis said the company estimates it would take four years to build a new launch site from scratch, but Relativity intends to have Launch Complex 16 ready in less than two years.

“We will have to go in and build and renovate some of that infrastructure,” Ellis said. “We will be building a payload processing facility, a horizontal integration hangar for the rocket and payloads. We’ll also be installing propellant tanks and loading systems, lightning protection towers, really everything that’s required to make it a launch site.”

Environmental reviews of Relativity’s plans also need to be completed before full-scale construction can begin, according to Ellis.

“We were impressed with Relativity’s seasoned team and its innovative approach to space technology and we look forward to working with them as they continue the process to launch the Terran 1 vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station,” stated Thomas Eye, director of plans and programs for the Air Force’s 45th Space Wing.

Ellis said Relativity plans to invest “well over $10 million” to get Launch Complex 16 up and running.

“It’s going to be a significant capital investment,” he said. “On the jobs side, we will be starting to hire full-time people down in Florida probably close to immediately.”

Relativity has several managers with experience developing launch pads for other companies, including Chris Newton, a former SpaceX engineer who helped develop the Falcon 9 rocket’s launch pad at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, and prepared pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center for Falcon launch operations.

Another recent hire was Tim Buzza, who is advising Relativity Space after long stints at Boeing, SpaceX and Virgin Orbit. Buzza led teams that developed SpaceX’s Falcon 1 launch pad at Kwajalein Atoll and the Falcon 9’s Complex 40 launch pad at Cape Canaveral, and served as SpaceX’s vice president of launch.

“We have some pretty heavy firepower for building up facilities like this,” Ellis said.

Relativity is looking at launch sites for missions with payloads needing to go into high-inclination orbits, a destination not reachable from Cape Canaveral. Ellis said discussions are underway between Relativity and officials at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, and at the Pacific Spaceport Complex on Kodiak Island, Alaska.

The Terran 1 rocket will be expendable, like many of the small satellite launchers now in development. Ellis said Relativity could debut new products to take advantage of the flexibility of 3D printing, and did not rule out future forays into reusable rockets.

Relativity is one of dozens of organizations working on smallsat launchers. One survey of the smallsat launch market by Carlos Niederstrasser, an engineer at Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems, concluded there are around 100 small launchers currently flying, in development, or were recently canceled or stalled.

Industry officials do not expect such a high number of rockets to become commercially viable, and Relativity will face stiff competition with companies like Rocket Lab, which already has declared its commercial Electron rocket operational after three straight successful flights to low Earth orbit last year.

Rocket Lab has flown all its missions to date from a privately-operated base in New Zealand, but plans to construct a new launch pad at Wallops Island, Virginia, this year.

Virgin Orbit’s air-launched rocket could make its first orbital test flight in the next few months off the coast of Southern California, and Vector Launch claims it will be ready to conduct its first launch to orbit this year from Alaska. Firefly Aerospace’s new Alpha launch vehicle is scheduled to lift off for the first time by December from Vandenberg.

Ellis said the Terran 1 rocket, which is one of the larger light-class launchers in development, will be available to deploy constellations of small satellites for commercial operators and the U.S. government. The military demand for a low-cost launcher like the Terran 1 was “one of the big considerations” for selected a launch site on Air Force property at Cape Canaveral, Ellis said.

“I think it’s a huge honor, first of all, but also really important … to be in that ecosystem because launch, I view as a national security consideration,” he said. “There is somewhat limited infrastructure, and being granted a pad is really important.

“We see an interest because of the technology approach we’re taking,” he said. “Flexibility is one big one. That ability to change payload fairing dimensions because we don’t have fixed tooling has been really interesting, and also getting toward a very rapid production cadence.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.