I Fell Under the Spell of NASA’s Most Notorious Thief

Before Thad Roberts stole more than $20 million worth of moon rocks and Martian meteorites, he made me want to reach for the stars.

I first heard of Thad Roberts during a lecture on black holes. November 18, 2000, was the University of Utah’s Science Day, a grand affair for visiting high-school students like me; the lecture hall was packed. The professor began by invoking the name of the 18th-century natural philosopher John Michell, whose theory of a “dark star” was the forerunner of today’s black hole—a fuel-spent star so compressed by gravity that even light bends to its will.

The lecture then took a detour. The professor boasted that the university’s own rising star, Thad Roberts, had just been accepted to NASA’s internship program. At 23, Roberts was a triple major in physics, geology, and geophysics, as well as the founder of the Utah Astronomical Society. He was determined to be the first person on Mars. He was also about to change the trajectory of my life.

After the lecture, I asked my undergraduate guide, who was friends with Roberts, to pass him my email address. I wanted to be an astrophysicist, but my ambitions conflicted with my upbringing; as a 16-year-old Mormon girl, I felt pressure to focus almost exclusively on home, family, and church. I didn’t feel confident that I belonged in science. Maybe this rising star could light the way.

Roberts soon wrote back, offering to help, and he became my unofficial career counselor. But then the Mars-bound intern captured headlines for a different reason: In the summer of 2002, he stole more than $20 million worth of moon rock and Martian meteorite samples from under NASA’s nose. He was caught in an FBI sting in Florida and spent six years in prison.

The heist sabotaged not only Roberts’s own goals of space travel but also those of his accomplices: fellow NASA interns Tiffany Fowler, then 22, and Shae Saur, then 19. “Being an astronaut is something I had planned to do and aspired to do my entire life,” Saur told the Houston Chronicle before she was sentenced. “My own actions have shattered that dream.” The two Texan women were given three years’ probation and required to repay NASA $9,000 in damages.

In the years since, Roberts has received a great deal of media attention, including a TEDx talk based on a book he wrote in prison and the writer Ben Mezrich’s version of the tale, Sex on the Moon: The Amazing Story Behind the Most Audacious Heist in History. Million Dollar Moon Rock Heist, a documentary by Icon Films, aired on the National Geographic channel in 2012. In contrast, Fowler and Saur have faded from public sight.

Why the two women joined him remains unclear; neither could be reached for comment. But accounts over the years suggest that Roberts was talented in recruiting others to accompany him in sometimes risky exploits. One of the FBI officers interviewed in the Icon Films documentary said of the court ruling, “I think the judge was very sympathetic. She realized that Thad manipulated them and that this was out of character for them.”

Recently, I interviewed Roberts to ask him myself why he stole moon rocks from NASA. His story still haunts me because I was part of its prequel: Before he apparently charmed Fowler and Saur, he charmed me.

Thad’s first email came a few days after my Science Day visit to the University of Utah, in 2000. “I heard from Oliver that you have some questions about becoming an astronaut. Feel free to ask me anything you like,” he wrote. Even digitally, Thad exuded confidence, from his “astronaut_thad” Yahoo handle to the three inspirational quotes on his automatic signature. One was unabashedly his own: “Passion is the essence of the human soul, to be truly alive is to kindle that fire within and explore your passions. —Thad Roberts.”

In the flurry of emails that followed that winter, Thad asked whether I wanted to visit the moon or Mars as casually as asking whether I wanted a hamburger or a hot dog. Because he was still an intern, alternating semesters between NASA and the University of Utah, he encouraged me to join him in learning skills he felt would give us an edge in applying for full-time positions at NASA. Learn Russian and Japanese, he said. Start attending astronomy nights. Get your pilot’s license.

A month later, after my 17th birthday, Thad offered to take me flying. He asked which high school I attended.

“You won’t come stalk me or anything?” I wrote.

“Just give me any info that you are comfortable with me knowing,” he responded. To assure me he was no Ted Bundy, he sent a picture of his wife, Kaydee, visiting him in NASA’s lunar lab. Both of them were wearing protective gear as they handled moon rocks. “Cute, isn’t she?” he wrote. Kaydee was pursuing modeling back in Utah, and she often accompanied Thad on his many outdoor adventures. I assumed the couple were Mormon—a common mistake in Utah—but they’d left the faith several years earlier. (Kaydee has since returned to Mormonism.)

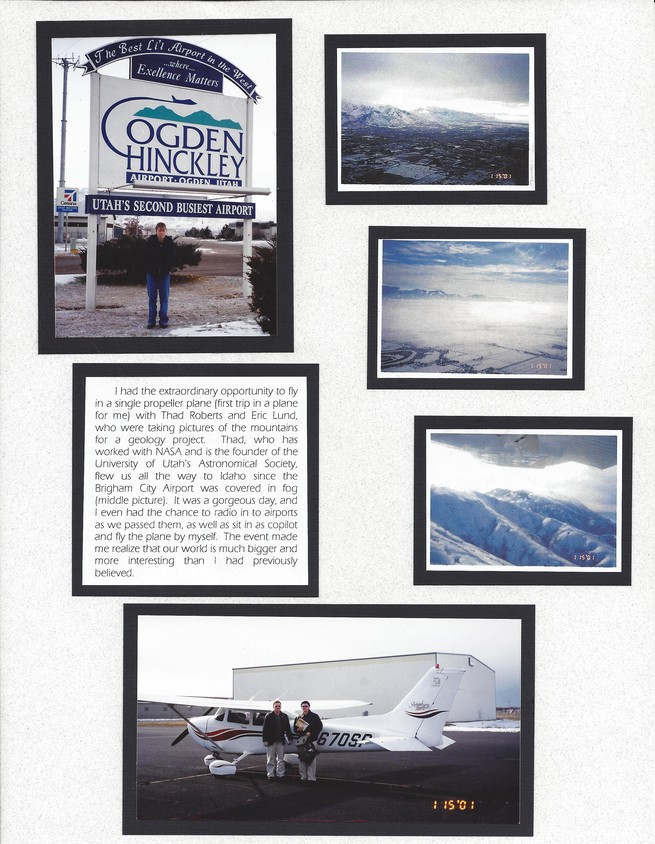

My constant begging and a reassuring phone call from Thad had persuaded my protective parents to let me board a single-propeller Cessna with a stranger who’d barely earned his pilot’s certificate. How could he be dangerous if he was a happily married man who worked for NASA?, I’d argued. In the frigid waiting room of the Ogden-Hinckley Airport, my father and I met Thad and a friend of his who joined us for the flight. Thad had a warm smile, a firm handshake, and disarming green eyes. His stocky outdoorsman build gave the impression that he was a man who did things and did them well.

“We’ll be back in an hour,” Thad told my father, and I buckled up in the back seat of the plane. The jolt of vertigo I felt was forgotten as we ascended: The fresh snow on the Rocky Mountains blinded me as early-morning light shone through silver-white clouds. “Eeeeexcellent,” Thad said, quoting Mr. Burns from The Simpsons. “Time for the first zero g.” My stomach screamed as Thad tipped the nose of the plane into a steep dive. I saw fast-approaching white fields out the front window. My body was weightless; I’d been momentarily set free from the gravitational power of my planet, a wonderful and terrible sensation. Thad yee-hawed.

As he started climbing again, I felt triumphant. This is what space is like, I told myself. I could do this. Who needed a multimillion-dollar Vomit Comet when you had Thad Roberts for a friend?

The rest of the flight didn’t go as planned. Before we returned to my frantic father much later than promised, we got lost and landed in a deserted airport in Preston, Idaho. Thad’s friend was feeling sick, so Thad offered me the co-pilot’s seat, and he guided me in managing the rudders and lifting the plane off the ground. My first time in a plane, and I’d flown it. When we were again soaring through the wintry air, I peppered Thad with questions about black holes. I didn’t fully understand his answers, but the fact that he knew them still made me feel important.

“Hey, want to see a cool trick?” Thad asked at one point. He cut the engine.

While unnerved by Thad’s antics, I was still thrilled to be making steps toward a career in astrophysics. Soon after our flight, I asked him for help making a portfolio for a statewide scholarship competition for graduating high-school students. We met during spring break in the University of Utah’s computer lab, where he helped me build my first HTML webpage. I posted an image of the Eagle Nebula, new stars forming in its clutching fingers. To me, it was an image of hope, of the chance to escape the prescribed orbit set for me by my religious culture.

Thad offered to give me a quick tour of campus. I mentioned that my father had once worked for the university’s cosmic- ray research group, and he showed me their building. He encouraged me to ask them for a job interview, something that hadn’t even occurred to me to try. When you put yourself out there, Thad said, opportunities come to you. Cliché, but correct: For the next three summers, I would intern for the group, learning how to program, to solder, to track down cosmic rays with air-fluorescence detectors in the Utah desert.

It didn’t take long, though, for Thad’s mischievous side to reappear. At the end of that campus tour, Thad led me to some large orange tanks in the basement of the South Physics Building. After pouring liquid nitrogen into a two-liter bottle, he brought me up to the roof, then sniggered as he dropped the bomb off the side of the building, rattling windows across campus. The rattling shook me, as well. Maybe I’d put too much trust in this man.

I consciously distanced myself from Thad after that, focusing on my summer internship and the demands of senior year. Thad emailed me once more the following spring about an upcoming University of Utah astronomy night. He was setting up the telescope’s solar filter for sunspot viewing—on the same roof where he’d thrown liquid-nitrogen bombs. Would I like to join him and the others? In the waning light, after seeing sunspots for the first time, I showed Thad the portfolio he’d helped me create, complete with pictures from our flight and from my internship with Cosmic Ray Research. He was delighted to hear I’d won runner-up in the scholarship competition.

Three months later, on July 13, 2002, Thad stole a national treasure. The plot had been forming throughout the time I knew him. Early in 2001, during Thad’s visit to NASA’s lunar lab in Houston, Texas—the trip when he posed with his wife for the photo he later sent me—he spotted a 600-pound safe containing lunar samples from almost every Apollo mission. These were “contaminated” rocks, still useful for certain research but no longer sealed in nitrogen for safekeeping. Thad noticed that the NASA senior scientist Everett Gibson opened the safe by first looking at something written on the back of its label. Hearing other scientists bemoaning their tight budgets and wishing they could sell some of these rocks, Thad began concocting a fantasy of how someone might steal them.

That same year, Thad met a student named Gordon McWhorter during another rooftop astronomy night, and McWhorter agreed to research how to sell moon rocks. Using the alias “Orb Robinson,” he emailed a Belgian amateur mineralogist in May 2002. The mineralogist, Axel Emmermann, suspected a hoax and alerted the FBI, who took over the online correspondence by pretending to be Emmermann’s sister-in-law. To Thad, it looked as if they’d found someone to buy the moon rocks he’d not yet stolen.

A month later, during the last round of his NASA internship, Thad met Tiffany Fowler and says that he immediately fell in love with her. Thad claims that he and Kaydee had grown apart as they followed their separate dreams, and they’d decided to have an amicable open marriage. Kaydee, however, says she had not agreed to this. “Thad has put so much incorrect info out there,” she wrote in a Facebook message to me, “so he seems like a hero to others instead of the lying, manipulative person he really is.” In an episode of the television series Who the (Bleep) Did I Marry?, Kaydee claims that when she confronted Thad about Fowler, he told her that she “didn’t understand his relationship with Tiffany. He was using her for something.”

Some facts of the heist remain murky, with certain details varying across reports—including the Icon Films documentary, the FBI’s account, and stories by the Los Angeles Times, the Orlando Sentinel, Science, CBS News, and other publications. Thad now admits he initially “just let people go with” some of the more exaggerated claims. What seems clear is that a week before the heist, Thad told Fowler of his plan to steal the moon rocks. Thad’s friend Shae Saur joined them just a few days after Fowler. While Saur waited in a borrowed Jeep outside NASA’s Building 31N, Thad and Fowler cracked the four-digit combination on NASA’s lab door. They arrived at the safe, and Thad pulled its label off, sure he’d find Gibson’s code on the back. The label proved worthless; it was only an algorithm that Gibson had created to remember the combination. So Thad and Fowler used a heavy-duty dolly they’d brought to wheel the entire safe out to the Jeep.

Back in a motel room, the three interns broke open the safe with a power saw and cataloged the lunar samples in vials. Then they discarded the safe, along with a set of green notebooks that represented 30 years of Gibson’s research. (In court, Thad denied that the notebooks were in the safe, but Fowler and Saur told the FBI he had insisted on throwing the notebooks out.)

Hiding the samples and the meteorite in Fowler’s apartment, the trio returned to NASA as if nothing had happened. A week later, Thad and Fowler drove to a hotel in Orlando, Florida, to complete the sale. In a romantic gesture before the meeting, Thad told me he put a few vials of moon rocks under Fowler’s hotel pillow—unbeknownst to her—wanting to say he’d had sex on the moon. Thad embellished this detail in previous interviews, telling CBS News that having sex on top of moon rocks was “uncomfortable.”

McWhorter joined Thad and Fowler, and the three met Emmermann’s “sister-in-law,” the undercover FBI agent, at an Italian restaurant. Thad proudly told her the whole story. Thad, Fowler, McWhorter, and Saur were all arrested and eventually sentenced. (Thad, Fowler, and Saur pleaded guilty; McWhorter denied the charges but was convicted at trial.) Kaydee sent Thad divorce papers.

Meanwhile, in a cubicle at Cosmic Ray Research, I stared, horrified, at Thad’s mug shot in the newspaper after his arrest. It wasn’t even his first theft, I learned: An FBI search of Thad’s home had revealed fossils stolen from the basement of the University of Utah’s Natural History Museum. The mentor who believed in me turned out to be a con man.

While I’ll never get on another plane with Thad, he has served his years in prison, and he is trying to move on. Instead of fleeing from science, he now puts forth theories on quantum gravity as a “philosopher of physics,” according to his website. As a public speaker, he urges people to commit to their dreams and rebound from their mistakes.

Over the past year, I’ve reestablished contact with Thad to better understand why he gave up the very dream he’d encouraged me to seek. He immediately responded to my email, agreeing to an interview on Skype. He was as charming as I remembered him, although he appeared more careworn and subdued. I finally asked him the question that had plagued me for almost 20 years: Why steal the moon rocks in the first place? Was it for money? I didn’t believe it was for love, since he’d been planning the theft well before he met Fowler.

“To feel good enough,” he said. This surprised me—he had always seemed sure of himself. Kaydee, too, says she saw him as a confident person. But Thad claimed he’d felt insecure from the beginning, terrified from day one of his internship with NASA. He was afraid of being abandoned by Fowler, his new lover; worried about losing his wife; and unsure he’d be able to provide for both of them. It didn’t help that at 19, at least according to Thad, he’d been sent home in disgrace from his Mormon mission for confessing to premarital sex—and, subsequently, thrown out of his home in Syracuse, Utah, by his family.

Kaydee was the one, Thad insisted, who believed he could make it to NASA, a fact she also confirmed to me. She was even willing to get another part-time job to support him. Although he was newly involved with Fowler, Thad said he wanted to support her dreams in return. Stealing the moon rocks would solve the problem. Anytime he started doubting his plans, he’d tell himself he’d already decided to do it and dismiss the fear.

The more I reviewed Thad’s history, the less the label con man—or its back-formation, confidence man—seemed to fit him. Con artists use a show of confidence to trick their “marks” out of money or other valuables. They’re people who overpromise and under-deliver on purpose. Thad, in contrast, was a simple thief. Led by his own irrational justifications and the conviction that he could evade capture, he was willing to persuade accomplices to join him, abuse the trust his employers placed in him, and deliver stolen goods to a buyer as promised.

Months after our initial interview, Thad emailed to say he was in Utah and wanted to meet for lunch. We met at The Pie Pizzeria, a dimly lit, underground restaurant adorned with graffiti. Thad had asked whether he could invite additional friends, and he brought a full contingent with him: one of the women he is currently dating, on her way to live with her other boyfriend in Canada; a camping friend; a prison friend; and a friend from one of his old philosophy classes. Thad still drew people together.

The conversation was amiable and casual. At some point, Thad revealed that he had dumped his entire life savings into a new online business venture. “I haven’t regretted it yet,” he said. “I thought, I’m a divorced, two-time-loser felon. This is my last chance for security. Let’s go.” Despite this bleak assessment, Thad held on to the idea that if you put yourself out there, opportunities come to you.

I stood to go, and Thad rose to give me a hug. I told him, genuinely, that I wished him all the best. For years, I’d thought of Thad as my own dark star. He’d drawn me into orbit around him, and I’d let him overrule my sense of what was smart and safe. But people are more complex than black holes. We can change course if we choose.

For so long, I’d wasted time and energy seeking assurance that I belonged in science. Last summer, almost 20 years after my first lesson on dark stars, I started working for Cosmic Ray Research again. This time, I’m confident that I can do it.