Virgin Galactic chief pilot Dave Mackay owes his title of being the first Scottish-born astronaut to the excitement of growing up during the space race, looking on in wonder as man made it to the moon.

The 62-year-old was at the helm of a test flight which entered space earlier this year, achieving a lifelong ambition shaped by watching the Apollo missions in his early years.

His interest was first piqued in 1964, when he received a book titled Exploring Space as a Sunday school prize.

Delving through its pages, he dreamed of going beyond where even the RAF jets that zoomed above his head in his home village of Helmsdale could go.

And as the US and the Soviet Union vied to cosmically outdo each other, he began to see a path towards becoming just like the astronaut pictured on the Ladybird book’s cover.

“The space race was a very exciting time,” he says, remembering teachers at school wheeling in television sets to show the black and white footage of Apollo missions blasting off.

“I watched with a sense of wonder. I remember being amazed at how the spaceship was navigated towards a moving target in space and how NASA could calculate rocket burn times to the second to get them into orbit around the Moon so precisely.”

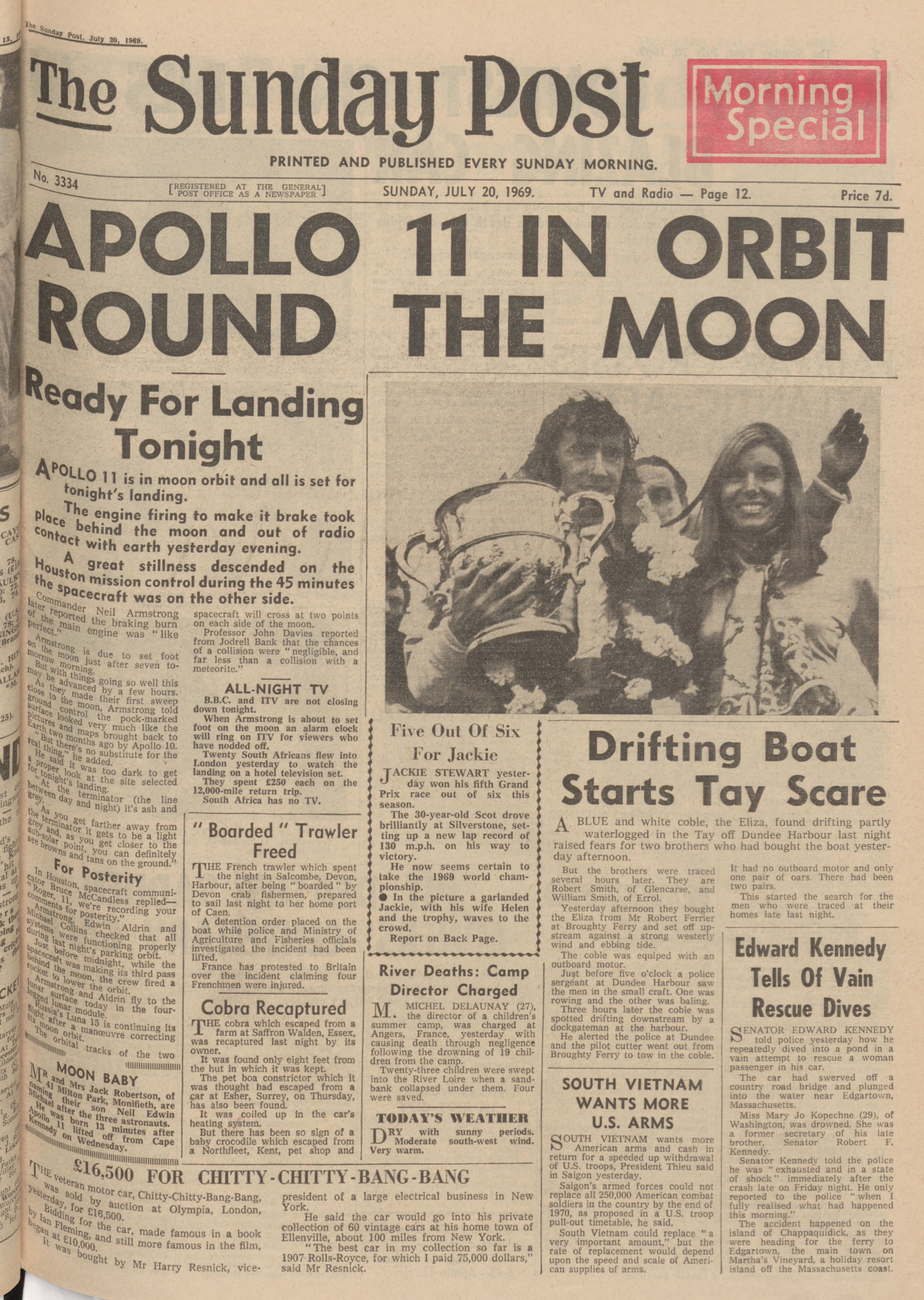

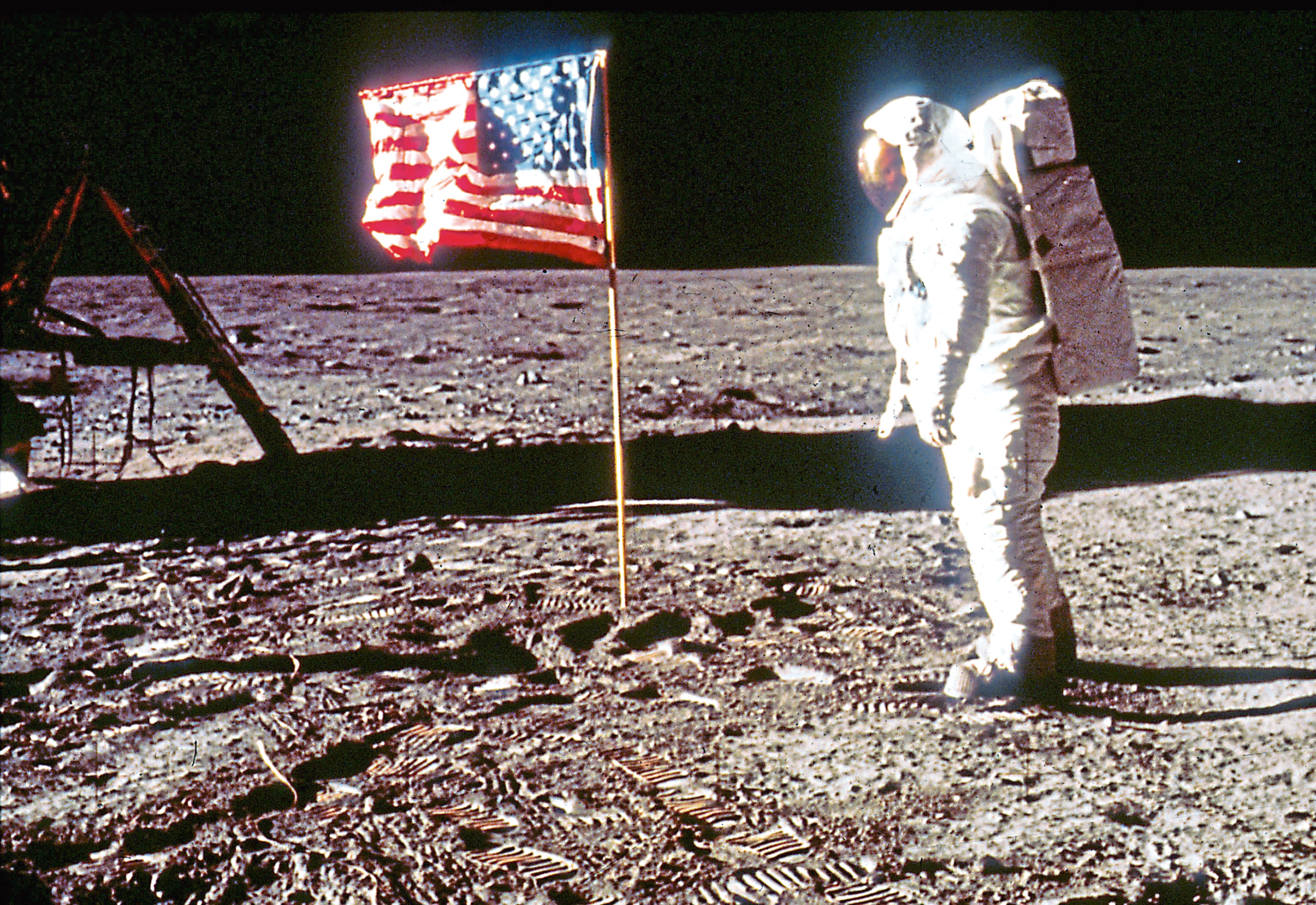

On July 20, 1969, millions tuned in to see Neil Armstrong utter the famous words “that’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” as Apollo 11’s landing craft successfully arrived on the moon.

In the UK, BBC and ITV television channels didn’t shut down for the night as usual, instead continuing to broadcast the captivating images from hundreds of thousands of kilometres away.

ITV even set up an alarm clock tone to ring and wake viewers up when Armstrong made the momentous step out from the capsule.

It was a mission that Dave reckons remains one of the most important advances in human history.

“As Neil Armstrong stepped on to the surface, there was still that slight doubt in my mind about just how solid the surface was,” he says.

“I remember looking up at the Moon in the night sky and in awe that humans were actually on its surface.

“I recall the newspapers the next day, with the front page spilt between news from Earth and news from the Moon. It was a very special and inspirational time.”

As a pilot, Dave recognises just how tough the mission was, especially with the obstacles that arose and without the technological capabilities of today.

And he believes that Armstrong’s skill in touching down safely on the moon was even more impressive than taking those famous first steps.

“The actual landing was very much more complicated than actually stepping on to the lunar surface itself,” he explains.

“Almost immediately from when Neil and Buzz started their descent from lunar orbit towards the surface they had communication problems, radio calls to and from Mission Control were broken and distorted.

“Next, they noted that features on the surface were appearing earlier than expected. It was later realised that this was due to mass concentrations on the Moon (some parts are more dense than others), causing a small change in the gravitational field.

“At the time this was unexpected and, if correct, meant they were going to land well beyond their intended landing point.

“Then the computer – vital to the control of the lunar lander and the success of the landing – started issuing alarms, and almost no one in Mission Control knew why.”

As soon as the astronauts started to see the touchdown point, Armstrong realised that they were going to land in a boulder field.

He took over manual control and started looking for a better place to land but, by now, fuel was getting very low.

When they finally found a good landing area and touched down, a mere 16 seconds of flying time remained.

“All of this occurred as humans were attempting their very first landing on a body other than the Earth with millions of the planet’s people riveted to their radios and televisions, following the events live,” Dave adds.

“It’s hard to imagine a more high pressure event – undoubtedly, the greatest feat of flying in aerospace history.”

Fast forward half a century and Dave has finally had his own momentous moment in space as part of a long and distinguished flying career.

As chief test pilot for Virgin Galactic, he was at the helm for their most recent foray beyond the NASA-defined boundary of space at 50 miles up.

Armed with swatches of his family tartan and his trademark tartan stripe on the rear of his helmet, he uttered some lasting words of his own: “welcome to space, Scotland.”

Last week, Virgin Galactic took steps to becoming the first publicly trading commercial space flight company, aiming to make space tourism a reality in the coming years.

And while walking on the moon – last done by Apollo 17’s Gene Cernan in 1972 – isn’t likely to be an option for passengers for many years, let alone professionals, the ambitious goals of companies wanting to take people into space are as lofty as those of the space race.

Dave isn’t surprised that space travel still evokes such excitement and wonder decades on from the moon landings of 1969.

When people visit his team working hard on providing the next big breakthrough in the heat of the Mojave Desert in California, Dave is met with a sea of awestruck faces as they gaze upon the vehicles that may one day make space tourism a reality.

“I believe it’s inevitable we will return to the Moon,” he says. “NASA is once again focused on going back – funding permitting but, now, several other nations are too.

“It is in our very nature to explore and the Moon is the first step in expanding into the Solar System and beyond.”

Asked if he himself would one day like to follow in Armstrong’s footsteps, and join only twelve men to have walked on the moon, Dave replies emphatically: “Absolutely! Why would anyone not want to do that?”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SSPL/Getty Images

© SSPL/Getty Images © DCT Media

© DCT Media

© Virgin Galactic

© Virgin Galactic