That Time NASA Wanted to Build a Floating Airport on Lake Erie

In the years after World War II, the sky was the limit for Cleveland. The city’s population climbed toward 1 million, and its proximity to half of the U.S. and Canada, along with the multiple corporations that used the city as their headquarters, led to local businesses advertising it as “the best location in the nation.”

One of the industries that powered Cleveland to its mid-century prominence was aeronautics. In 1925, the city became the first in the country to have a municipal airport, and 22 years later, it led the way in building the first downtown airport: Burke Lakefront along the Lake Erie shore. Cleveland was home to TRW, which made aviation and auto parts, and sponsored the National Air Races of the 1920s and 1930s, drawing all the swashbuckling flying heroes of the day and raising the city’s profile in the field of aviation.

What’s now known as the I-X Center in Cleveland, a convention hall next to Hopkins International Airport, was originally built to manufacture bombers during World War II. And in the 1940s, Cleveland became home to a facility for the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA), which in 1958 became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

Four years later, President John F. Kennedy announced a plan to go to the moon by the end of the decade.

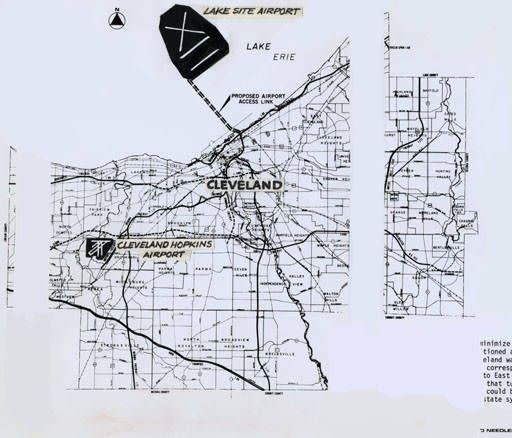

In 1969, as that giant leap loomed tantalizingly close, a NASA official in Cleveland announced another idea that seemed just as far-reaching, and just as initially implausible: a new airport, capable of accommodating the largest jets being made and supersonic transports. The airport would be an enormous transportation hub offering luxurious accommodations to travelers and access to all the transportation Cleveland had to offer.

And it would sit right in the middle of Lake Erie.

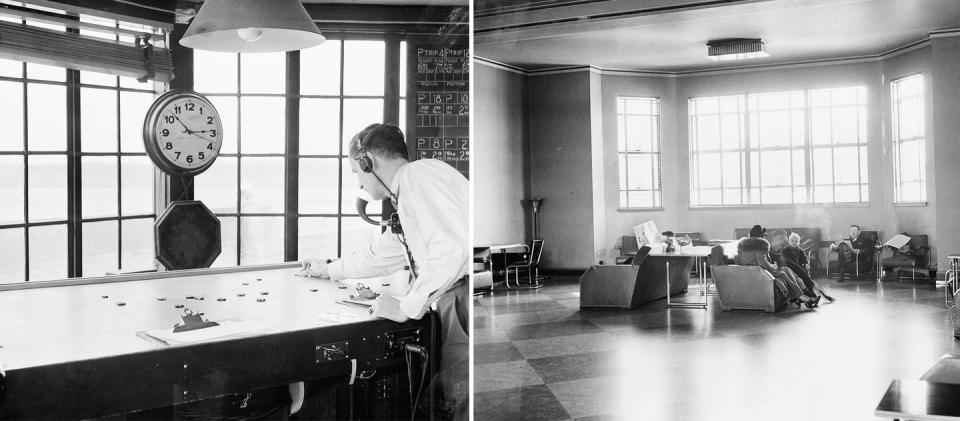

When Cleveland’s municipal airport opened in 1925, it was a state-of-the-art structure, with its glass Art Deco waiting room and an air traffic control center, also the first in the nation. But the Great Depression and World War II didn’t leave a lot of time or resources for any type of renovation, and a generation later, it had become old and shabby.

While the airport built a new terminal 1956, some were concerned it wouldn’t be enough, particularly as larger jet airplanes were starting to supplant propeller planes. More space was needed for the newer, bigger planes—and for the millions of (largely upper-middle class or rich) passengers expected to ride them.

“Flying was supposed to be a glamorous thing, but the terminals they were flying out of seemed old, tired, and small,” says Janet Bednarek, a history professor at the University of Dayton who has written several books on the history of commercial aviation. “It didn’t fit what flying was supposed to be about.”

And there was little room to expand at Hopkins.

“Most airports were out in areas that were becoming increasingly suburban at that point,” Bednarek says. “They were built away from the cities because land was cheap, but people were moving out to those areas. They had good access—because there was an airport there.”

The predominant issue with airports was the noise. (Famously, Toledo Mayor Carty Finkbeiner once suggested that noise complaints near his city’s airport could be ameliorated by moving deaf residents to the houses around it. Really.) When officials sought sites for additional runways in the 1950s, protests grew louder, with hundreds of people signing petitions to keep an airport out of the farmland in adjoining counties.

“And of course, by the 1960s, we were absolutely going to be flying supersonic,” Bednarek said. “This idea of building airports in water, away from cities and away from neighbors, was very attractive.”

It also wasn’t new. In the 1930s, officials suggested floating airports for the Thames River in London and the Seine River in Paris. Noted industrial designer and futurist Norman Bel Geddes—he of the Shell Oil City of Tomorrow and the Futurama at the New York World’s Fair—even, well, floated such an airport off the southern tip of Manhattan.

Not long before the Cleveland proposal, Detroit and Chicago also pursued the idea of a floating airport in Lake Michigan. But the plan found the most ardent supporters in Cleveland. In 1926, a year after the municipal airport opened, Maj. Jack Berry suggested something off downtown. In 1958, engineers built a runway at Burke Lakefront.

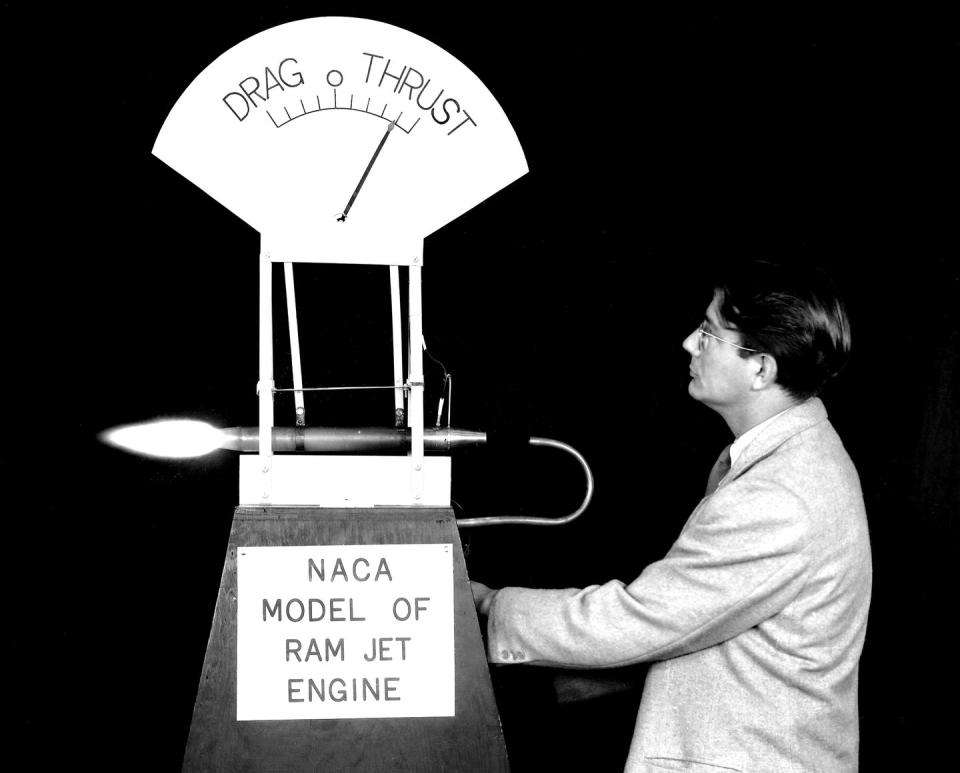

If there was anybody who could make the proposal of an airport built in Lake Erie sound feasible, it was Abe Silverstein, a Terre Haute native who the NACA hired right out of Rose Polytechnic Institute (now Rose-Hulman) in 1929.

Heralded as the architect of America’s space program, Silverstein helped design supersonic wind tunnels. When the NACA, based in Cleveland at the time, reorganized into NASA by the end of the ‘50s, Silverstein led the planning and naming of what became America’s manned space flights over the next decade. Silverstein was also instrumental in developing liquid hydrogen as rocket fuel, based on his research at the Lewis Center in Cleveland, since renamed for Ohio native and astronaut John Glenn.

In 1961, Silverstein said a moon landing within the decade was more than feasible. So his suggestion of a Lake Erie airport carried serious credibility.

“Silverstein was the idea man and the main advocate,” says Norman Krumholz, who served as the city’s planning director from 1969 to 1979. “It was a big project.”

Silverstein spent two years in secret coming up with a detailed plan on an airport, which he announced in early 1969, shortly before his retirement from NASA—and just a week after Boeing first flew the 747, what was then the largest passenger jet in the world. He then ended up with the Greater Cleveland Growth Association, which championed the project. By then, Cleveland was badly in need of a boost.

“The city was fighting decline and trying not to fall down the urban hierarchy,” Bednarek says. “In those cases, people turn to big, splashy projects to reverse things.”

Silverstein’s plan, to put it mildly, was enormous.

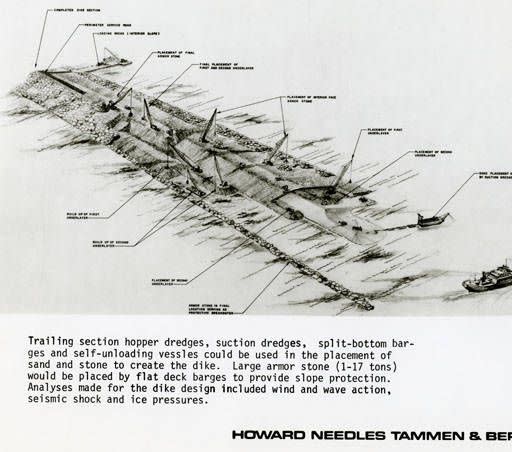

Termed an “Aeronautical Disneyland,” the proposal called for an island to be built about a mile out from the Lake Erie shoreline just east of downtown, served by a 13-lane causeway for auto, truck, bus, and train traffic. (Just the year before, Cleveland became the first city in the Western Hemisphere to connect its downtown by rail transit to an international airport.) The city would also have to build dikes to construct the island and fill them with 86 million 1-ton cubic yards of fill dirt dredged from the lake’s bottom.

The terminal itself, with one story above the flight deck and three under it, would be 10 times the size of the Pentagon, the world’s largest office building at the time.

Despite the planned grandeur, Silverstein’s proposal received widespread backing from city and county governments, which threw elbows to see who would appoint people to the Lake Erie Regional Transit Authority, the organization that oversaw further study. Governor James Rhodes was willing to work on the project’s behalf, as were Congressional representatives from Ohio. Both of Cleveland’s newspapers, the Press and Plain Dealer, backed at least the study of the idea.

Lawyers and brokers, meanwhile, practically salivated at the idea of writing and issuing $1 billion in bonds, at the time an unprecedented number. Labor unions also fell in line, foreseeing at least 2,000 well-paying construction jobs in the decade it would take to build the jetport, and thousands more as it became a widely used hub for passenger and cargo transport.

Not to say there wasn’t opposition. Environmental activists, some aligned with Ralph Nader and his “Nader’s Raiders,” opposed the plan, as did a young firebrand on city council named Dennis Kucinich. But they were voices in the metaphorical wilderness. “The consensus was to at least look into it,” Krumholz says. “There were many interested factions.”

In his plan, Silverstein estimated that by the end of the 20th century, more than 46 million people would fly in and out of Cleveland, which Bednarek charitably describes as optimistic.

“In airport construction,” she says, “there’s a lot of the idea of, ‘If you build it, they will come.’ But saying 50 million people would use it when regulation was still the rule of the day is willful disregarding of the way things worked at the time.”

At that point, air routes and fares were still set by the federal government through the Civil Aeronautics Board, and Silverstein pointed out that Chicago and New York airports were saturated, a situation on which Cleveland could capitalize by taking some of the spillover.

Over the next decade, $4.2 million was spent studying the feasibility, with more than $3 million coming from the FAA and the rest from private foundations. A weather station was set up to monitor precipitation, wind, and visibility on the lake. Lake Erie is the shallowest of the Great Lakes, which in some respects made it the most receptive to the project; the depth of the lake where the airport was built would be about 50 feet. But because it was so shallow, it was also the most susceptible to wind, leading to waves.

Additionally, Lake Erie was the easiest to freeze in the winter, and the airport could have even changed weather patterns. The east side of Cleveland and its eastern suburbs are prone to lake effect snow, where weather systems roll over the lake’s central basin, picking up moisture and dumping it in the form of snow on land.

As hard as it is to believe now, proponents touted the jetport as an environmental boon to a lake that in 1969 was described as dying. The dredging, they argued, would take algae and fill from the bottom of the lake, allowing for more marine life to flourish, and the airport would serve as a hedge against soil erosion.

“Dredging is not necessarily a good environmental solution,” Bednarek says. “It’s moving the pollution from one place to another. It was a bit of a stretch that it would improve the lake.”

Gradually, though, interest waned—not for environmental reasons, but for fiscal ones. In 1976, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) said there was no federal money to pay for the project, which by then would be $2 billion. The next year, the U.S. Department of Transportation said that Hopkins would be sufficient for Cleveland’s transportation needs until at least 2000. And that same year, Kucinich was elected mayor, and he had no interest in continuing with plans for the jetport.

The dream was effectively dead.

In May 1978, the FAA told the Lake Erie Regional Transit Authority that it wouldn’t receive any more funding. That August, Kucinich barely survived a recall effort as mayor. Two months later, President Jimmy Carter signed the Airline Deregulation Act, ultimately paving the way for the dissolution of the Civil Aeronautics Board. And in December 1978, Cleveland defaulted on $14 million in loans, the first city to do so since the Great Depression. It was as much a reflection of Kucinich’s fight with local banks as a result of the city’s fiscal crisis.

With deregulation, the airline industry became more market-driven than it had been in decades, and it was no longer possible for Cleveland to be assigned any spillover routes from crowded airports on the East Coast.

“The airlines started making the decisions, not the government,” Bednarek says. “And Cleveland had a big airplane and NASA presence, but no airlines.”

In fact, with its decline in population, corporate headquarters, and conventions, Cleveland wasn’t anywhere near the attractive travel destination it had been even 20 years earlier. United Airlines dropped from 110 flights out of Hopkins in 1979 to just 13 in 1988. And those estimates of 46 million passengers through Cleveland at the turn of the 21st century? Hopkins had 13.2 million passengers in 2000. It hasn’t been that high since.

Cleveland’s population has also declined steadily. In 1980, Columbus took over as the largest city in Ohio; today, Cleveland’s is now less than 400,000. The city also has the ignominious status as one of the poorest in the country.

Had NASA’s crazy jetport been built, Krumholz is adamant that Cleveland wouldn’t have suffered the population and jobs loss that it has. “It’s a lost opportunity, and in retrospect, the future might have been brighter.”

And Krumholz firmly believes that future burned out because of money—not might.

“Physically,” he says, “we could have done it.”

You Might Also Like