Cosmic fountain is polluting intergalactic space with 50 million suns' worth of material

The 20,000-light-year-long fountain of gas is moving at 450 times the top speed of a jet fighter.

Tremendous explosions in a galaxy close to the Milky Way are pouring material equivalent to around 50 million suns into its surroundings. Astronomers mapped this galactic pollution event in high resolution, obtaining important hints about how the space between galaxies becomes filled with chemical elements that eventually become the building blocks of new stars.

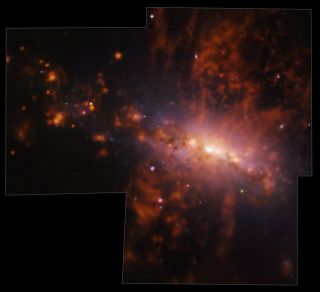

The findings came about when the international team studied NGC 4383, a spiral galaxy in the Coma Berenices constellation, using a Very Large Telescope (VLT) instrument called the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE).

Located around 62 million light-years from Earth, NGC 4383 is part of the Virgo Cluster and is undergoing a strange and turbulent evolution. This includes the galaxy spitting out an outflow of gas so great it stretches across 20,000 light-years of space. This gas jet, containing enormous amounts of hydrogen and heavier elements is traveling at speeds as great as 671,000 miles per hour. For context, that is around 450 times as fast as the top speed of a Lockheed Martin F-16 jet fighter.

Related: Hubble Telescope just witnessed a massive intergalactic explosion and astronomers can't explain it

"Very little is known about the physics of outflows and their properties because outflows are very hard to detect," team leader and University of Western Australia researcher Adam Watts said in a statement. "The ejected gas is quite rich in heavy elements, giving us a unique view of the complex process of mixing hydrogen and metals in the outflowing gas."

Watts explained that in the outflow of gas from NGC 4383, he and the team detected oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur and many other chemical elements.

These outflows are, in short, vitally important to the evolution of the cosmos. The elements they blast into intergalactic space will become the building blocks of the next generation of stars, planets, moons — and possibly even the foundation of living things that will someday come to dwell on those worlds.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team thinks the tremendous outflow of gas from this relatively close galaxy is the result of powerful stellar explosions at the heart of NGC 4383. That's because this region is in the throes of an intense burst of star formation. The most massive stars created in this bout of starburst are losing mass over their lifetimes via powerful stellar winds. After millions of years, stars like these die in violent supernova explosions.

Both stellar winds and supernova explosions drag out a galaxy's gas and dust, therefore depleting its gas reservoir. Because this reservoir provides the building blocks for new stars, that depletion has the effect of slowing — and eventually, stopping — star formation in galaxies that experience this phenomenon.

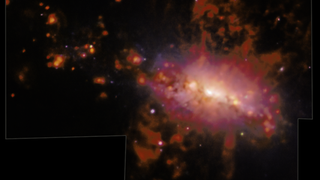

In the VLT/MUSE image of the galactic fountains of NGC 4383, this outflow of material can be seen as bright red filaments shooting from the main, central body of the galaxy.

The team's findings represent the first results from the MUSE and ALMA Unveiling the Virgo Environment (MAUVE) survey.

"We designed MAUVE to investigate how physical processes such as gas outflows help stop star formation in galaxies. NGC 4383 was our first target, as we suspected something very interesting was happening, but the data exceeded all our expectations," Catinella concluded. "We hope that in the future, MAUVE observations will reveal the importance of gas outflows in the local universe in exquisite detail."

The team's research was published April 22 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

Unclear Engineer Why is this described as "pollution" of inter-galactic space? Maybe it would be better termed as "fertilization" if the rest of the article is correct about this material eventually producing another generation of stars. But, do stars form in "intergalactic" space? Or, does the material need to get gravitationally dragged into the originating or some other galaxy before it can become dense enough to make new stars?Reply

And, what about the "filament" structure of this material? If it is really from a huge number of supernovas, I would expect some more cloud like structures, unless maybe the clouds are blocked in almost all directions and the "filaments" are only able to stream out of holes in the other material. What about some other theory for the filament structure, such as magnetic fields around or even between galaxies?