Colorado Springs doesn't build rockets or satellites, but in the booming new space economy, startups have picked the Pikes Peak region for a new and important job: Traffic cop.

At the Catalyst Campus incubator and in anonymous office parks around town, quickly-growing firms are working out how to avoid crashes in space amid plans from firms including Elon Musk's SpaceX to put thousands of new satellites into orbit.

It's a role the military once played, but has grown too large for even the Space Force that calls Colorado Springs home. But those military skills are what's drawing businesses here like miners to the Cripple Creek Gold Rush.

"I think it is pretty clear to say that no matter how this shakes out, Colorado Springs will remain the hub," said Todd Brost, who heads special programs for Numerica Corp., one of the new space traffic management companies that has come to Colorado Springs.

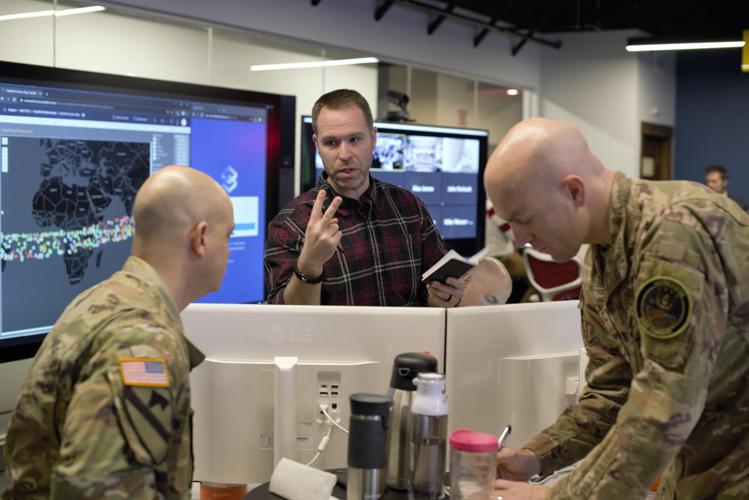

The status of Colorado Springs was on display in December, with a war-game style training session that drew dozens of companies to Catalyst Campus off Pikes Peak Avenue and drew international competitors from as far away as Australia to try out new tools for "space situational awareness," the industry term for tracking what's in orbit.

It was one in a series of planned events here, with another coming in April as Space Force and the Department of Commerce figure out how to better understand how best to track the growing commercial use of low-Earth orbit.

That's the easiest orbit to reach, and it's going to get busy. Commercial companies plan on launching swarms of mass-produced small satellites to provide broadband Internet worldwide, help companies track shipments, and offer on-demand imagery from space.

But as thousands of satellites are added, the problems with traffic in that orbit are growing more apparent. Picture the world's busiest freeway, with traffic traveling at 18,000 mph.

The lanes are unmarked, there are no traffic signals and the cars have no turn signals, minimal steering and no brakes.

A few years ago, the traffic wasn't a problem, because the only cars were government-owned Rolls Royces.

"The cost of the technology was a prohibitive blocker into who could play," explained Seth Harvey, CEO of Bluestaq, a Colorado Springs company that is helping the Space Force develop a data-sharing site that will make it easier for commercial satellite companies to track what's in orbit.

"Over the last two decades the cost of that technology has dropped considerably," Harvey said.

Satellites are smaller and cheaper. And new rocket companies, including SpaceX, have dropped launch costs, from $10,000 per pound to orbit a few years ago to about $1,000 a pound today.

It's like what happened to automobiles when Henry Ford figured out mass production.

"Space is the newest economy in the world and it is becoming integrated into everything we are doing," said Dan Ceperley, founder of LeoLabs, a Silicon Valley startup that's building space-tracking radars around the globe and recently opened a Colorado Springs office.

Protecting that new economy has become a top priority for Congress, which held hearings last week on the dangers of space junk.

The Department of Commerce's Office of Space Commerce boss Kevin O'Connell told a Senate panel that his agency wants to see U.S. investments in space protected.

"The United States currently has an opportunity to capture the lion’s share of an expected trillion-dollar space economy by 2040," he testified.

Commerce officials are examining how to bring order and safety to orbit. It's a new job.

While agencies including the Federal Aviation Administration have licensed and overseen rocket launches, no agency took over after satellites reached orbit.

"There hasn't been a regulator that has focused on activities in space," Ceperley said.

Air Force Space Command in Colorado Springs, which became the core of the new Space Force in December, was the default traffic manager. The military tracked 20,000 objects in orbit using telescopes and radars, sharing their data with commercial satellite companies.

But Space Force, and U.S. Space Command in Colorado Springs have bigger things to accomplish than worrying about satellites launched by Wall Street.

Rising anti-satellite efforts by Russia, China and other rivals drove the creation of the new space service branch, and it's not the space-version of the Coast Guard.

"The military is most focused on dealing with that contested space environment," said Brost, whose firm Numerica has worked with the military to build a network of space-scanning telescopes.

Brost should know. A retired colonel, he led the National Space Defense Center at Schriever Air Force Base before putting on a business suit.

The realm of space-tracking isn't all startups. Old-school defense firms like Boeing and Lockheed-Martin have worked with the Pentagon for years on similar issues.

But small businesses, with organization charts that would fit on the back of a business card, have proven adept these days at keeping up with the quickly changing nature of the commercial space business.

"My boss is the vice president for space systems and his boss is the president of the company," Brost said. "We can get on the phone and decide to do it that quick.

"The Air Force has been wooing small firms, sending officials to Catalyst and other places that gather startups and issuing same-day checks for promising ideas.

Bluestaq is a beneficiary of the federal fascination with space startups.

Started by four founders who roamed away from traditional defense contractors, Bluestaq got $150,000 in military seed money two years ago and has turned that into a $37 million contract.

What the company does for the Space Force isn't the makings of a "Star Trek" script. They're basically high-tech librarians, who compile and share satellite and space junk data with the military, allies and commercial firms.

"As the community of space grows, that secure digital data sharing is more and more important," Harvey said.

And the small companies don't want to become the big guys.

"We can't compete with Lockheed across the entire spectrum, but we are really good at what we do," Harvey said.

And small firms will take risks that would give accountants at the bigger firms fainting spells.

LeoLabs is building radars — two so far in Texas and New Zealand, with more planned — and hoping commercial companies will subscribe to get the data. It's Netflix for orbit.

"We take all the risk and we only get paid once we are delivering a quality service," Ceperley said.

The two radars, thanks to innovative software, are tracking bolt-sized objects that litter low-Earth orbit.

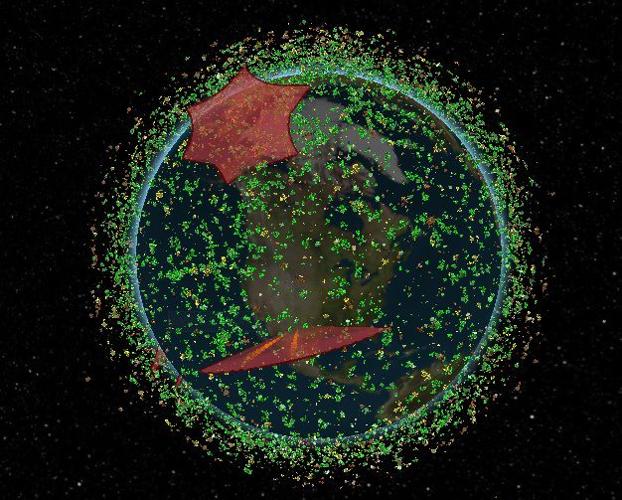

The Space Force catalog of low-Earth orbit traffic listed about 14,000 satellites and pieces of junk left over from launches dating to Sputnik and debris from crashes. Ceperley's company says it has spotted 250,000.

The data is used by customers, including the Space Force to avoid crashes. With items traveling at mind-blowing speeds in opposite orbits, even a bolt can trigger a catastrophe, Ceperley said.

"When things collide they create clouds of debris. Then that debris is up there for decades or centuries," he said.

With billions of dollars on the line for new space businesses, the traffic cops will play an ever-growing role.

And Colorado Springs has the best traffic cops.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices