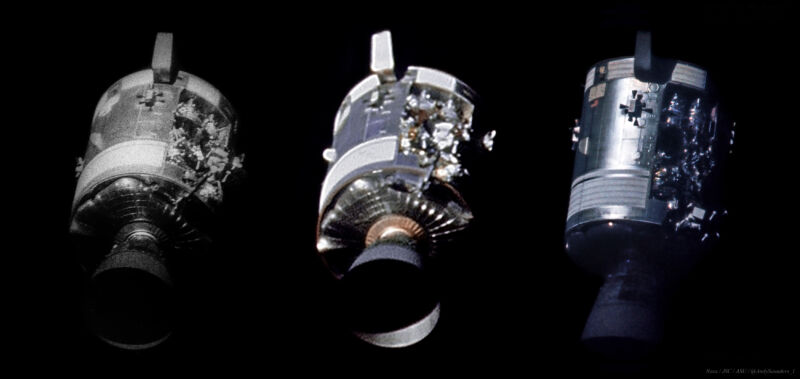

NASA's famous Apollo 13 mission launched 50 years ago, and on April 14 the oxygen tank on its service module exploded. As you undoubtedly know, the mission's Moon landing was canceled after the explosion, sending the three astronauts into a mad scramble with Mission Control to save their lives. Apollo 13 inspired an award-winning, eponymous film in 1995 starring Tom Hanks as commander Jim Lovell.

At Ars, we have chronicled aspects of the mission in great detail, putting it in the broader context of the Apollo Program, as well as going really deep on what exactly happened during the mission. For this story, we have a special treat—newly remastered images culled from 70mm Hasselblad photographs and stacked frames from 16mm film.

These images were processed and shared with Ars by Andy Saunders, a property developer and semi-professional photographer in northern England who is an Apollo enthusiast. In recent years, he has spent more and more time going into the Apollo archive to dig out new details from images and film. (A larger version of the damaged Apollo 13 service module can be seen here.)

Andy the artist

Saunders gained a love for the Moon as a child with the gift of a telescope. As he looked at the gray companion, he wondered what it would be like to visit there. After learning about the Apollo Program, he immersed himself in finding out more about the astronauts and the rockets and spacecraft. Later in life (he is now 45 years old), Saunders thought there might be a way to bring the Apollo program back to life.

In particular, he wanted to find more images of Neil Armstrong on the Moon. (Armstrong had the camera, so most images are of Buzz Aldrin). As Saunders reviewed fuzzy 16mm footage recorded by Aldrin from inside the lunar module, which showed Armstrong stepping out onto the Moon, he discovered that three of the images showed something of Armstrong's face. He stacked the three images to create a photo that shows Armstrong's face at the historic moment.

"For me, it was almost like being there, really, and going back in time to join them," Saunders said. "Especially when the clearer images come out. With the Armstrong image, it almost felt like I was behind the camera, inside the lunar module. At that moment, only me and Buzz Aldrin had really seen this." Saunders was hooked.

-

This gallery highlights images made from stacked 16mm film. Here, Fred Haise takes a nap, in a before and after image.Andy Saunders/Stephen Slater

-

Lunchtime during trans-Earth coast. The food on board was mostly freeze-dried, requiring mixing with hot water. However, with much of the LM shut down to conserve power, the only water available was almost freezing. Jack Swigert (right) appears to be enduring such an option, whereas Fred Haise got by on a few peanuts, mini cookie cubes and bread cubes. Jim Lovell (left) ate very little on the way back; the hot dogs that had frozen solid certainly didn't appeal. In fact, he lost 14lbs over the whole of the journey.Andy Saunders/Stephen Slater

-

This image shows, in some detail, the dark, cold, powered-down command module Odyssey prior to the crew re-inhabiting the stricken spacecraft for the final critical part of the mission. Having been powered down since shortly after the explosion, a detailed start-up procedure was determined in order to conserve the little energy that was remaining in the CM's batteries. The large docking hatch is prominent in the image, and the detail in the instrument control panels is visible around the window.Andy Saunders/Stephen Slater

-

One striking thing about the 16mm footage is how calm the crew members appear given the grave nature of the situation, the conditions, and the critical mission tasks that lay ahead. This perhaps belies the astronauts' true feelings as we know that, in reality, the crew doubted if they would make it home alive. This remarkably clear panorama shows Commander Jim Lovell's attempt at normality by selecting some music on the portable tape player as Jack Swigert is tucked up in the storage area taking a nap (right).Andy Saunders/Stephen Slater

-

This image shows Lovell (left), Swigert (center), and Haise (top right) together as they prepare for re-entry. Lovell rubs his hands to keep warm in the near-freezing conditions as they discuss details of the “Apollo 13 CSM Entry Checklist,” which contained the procedures necessary for the command module's re-entry into Earth's atmosphere.Andy Saunders/Stephen Slater

Astronauts took about 20,000 images on Hasselblad cameras during the Apollo program, and they're kept in a vault at Johnson Space Center. Periodically, the space agency will re-scan this film and release new versions of the images. Recently, Saunders said, the space agency put out new, raw, 1.3GB versions of each image, an upgrade from the previous 10MB JPEG versions. By using photo editing tools, Saunders has been able to push the processing of these images harder to bring out more details in pictures once set aside as too blurry or otherwise uninteresting.

Stacking images

A second technique involves stacking images from 16mm video film, often captured by astronauts floating in the command module with a handheld camera. In each frame, Saunders said, there is signal and noise. The noise is completely random, so from one frame to the next, it will be scattered about. But the signal in each frame will be more or less the same. Therefore, in slow-moving video, there are multiple frames showing the same scene. By "stacking" these frames, the signal comes through while the noise can be averaged out. This increase in the signal-to-noise ratio produces a clearer and more detailed scene.

Saunders sometimes does this stacking by hand and sometimes uses freeware used by astronomy photographers. More frames lead to better images. Saunders said he has processed Apollo images from as many as 300 stacked frames. "It's time-consuming, complex work," Saunders said. "But this is such important film. If this allows the general public to see more of it, it's worth the effort."

-

This gallery features processed Hasselblad images. This photo, from an underexposed high resolution scan, shows the dark LM with most of its systems powered down. Above the "8-ball" are some sticky handwritten notes, a reminder that they were now flying the LM in a very different way than they had trained for over the years.Andy Saunders/Stephen Slater

-

Here is the unprocessed version of the former image, showing the instrument panel. Rather than using the descent engine to land on the Moon, the crew was using it to get them—and the command module—home. Flying this "stack" of LM and CSM was “like flying with an elephant on your back,” according to Jim Lovell.Andy Saunders/Stephen Slater

-

Great image of the Moon taken as the crew passed around the far side.Andy Saunders/Stephen Slater

-

The Moon as seen through the LM window. Lovell chose not to look too much as they passed by, having seen it before on Apollo 8—and no doubt feeling the disappointment of the lost landing.Andy Saunders/Stephen Slater

-

A photo of Earth. The crew had to manually align with Earth's terminator during the critical manual course-correction burn that got them home safely.Andy Saunders/Stephen Slater

While working on Apollo 13 images, Saunders said he was struck by how calm Lovell and the other two crew members, Fred Haise and Jack Swigert, appear. Much of the film he worked on was shot in the lunar module, after the oxygen tank exploded. The crew was exhausted, it was cold, and the astronauts found themselves in the gravest of situations. And yet they appeared to be in good spirits. "That's test pilots for you, I guess," Saunders said.

reader comments

55