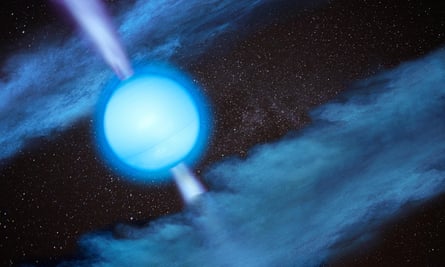

In 1967, a team led by the radio astronomer Antony Hewish, who has died aged 97, discovered pulsars, rapidly pulsating radio sources that turned out to be due to rotating, magnetised neutron stars, the ultra-dense collapsed remnants of massive stars.

This was one of the most exciting astronomical events of the second half of the 20th century: the precise timing of the pulses from these objects is more accurate than the best atomic clocks and has allowed precision tests of general relativity.

The team assembled by Hewish – Jocelyn Bell, John Pilkington, Paul Scott and Robin Collins – all played a crucial role in the detection and confirmation of the first pulsar, with attention naturally focusing on Bell, the research student who first noticed unusual signals.

Seven years later, Hewish and Martin Ryle jointly received the Nobel prize for physics, “for their pioneering work in radio astrophysics: Ryle for his observations and inventions, in particular of the aperture synthesis technique, and Hewish for his decisive role in the discovery of pulsars”.

Ryle and Hewish’s 1960 invention of aperture synthesis, where the rotation of the Earth is used to convert a line of telescopes into, effectively, a single giant circular antenna, was crucial to the development of radio astronomy. The Very Large Array in New Mexico, the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (Alma), the European Low-Frequency Array (Loray), and the Event Horizon Telescope used to map black holes are modern examples of their innovation.

Hewish’s first research was on propagation of radio waves through lumpy transparent media, and he realised in 1952 that the scintillation or twinkling of the recently discovered radio “stars” (actually radio galaxies or quasars) could be used to probe conditions in the ionosphere and the interplanetary medium.

Today these techniques are used to map large-scale structure in the solar wind. Hewish showed that interplanetary scintillations could be used to make very high-resolution observations of distant objects, equivalent to a telescope with a baseline of 1,000km.

He conceived the idea of a huge phased-array antenna with which a major survey of radio galaxies and quasars could be carried out, and secured funds to build one in 1965. Bell joined his team at this time and was given the task of analysing the paper strip-chart records from the array. It took all of them to build the 1.8 hectare (4.5 acre) array with its 1,024-dipole antennae.

Once it was commissioned, Hewish asked Bell to create sky charts of each day’s observations. Real astronomical sources would recur at the same position on the sky each day, whereas human-made interference would occur at random. On 6 August 1967 Bell noticed an unusual patch of “scruff” on the charts, which reoccurred from time to time at the same position on the sky.

Hewish decided to improve the time resolution on the recording equipment, and this showed that the source was pulsing every 1.33 seconds. Careful work by the team showed that the source was not an instrumental effect, or due to “little green men”, but was from a source located at 200 light years away. Bell also discovered three other pulsars. Hewish wrote the results up for publication in Nature, with Bell and the three other authors.

His interpretation was that the source had to be either a rotating white dwarf star or a neutron star. The neutron star interpretation was soon confirmed by the discovery of a pulsar with a much shorter period in the Crab Nebula. In an interview, Hewish said that when Stephen Hawking heard the news he rang up to say that if neutron stars existed then black holes were almost certain to occur too.

Born in Fowey, Cornwall, the youngest of three sons of Frances (nee Pinch) and Ernest Hewish, a bank manager, Antony grew up in Newquay, where he developed a lifelong love of swimming and boating. The family lived above the bank where his father was manager, and Antony was allowed to set up a laboratory there. One of his early electricity experiments blew the fuse of the entire building. At boarding school – King’s College, Taunton – he built a crystal set radio because ordinary radio was not allowed in the dormitory.

In 1942, Antony went to the University of Cambridge to study natural sciences. His studies were interrupted from 1943 to 1946 by war work on airborne radar countermeasure devices, at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough and the Telecommunications Research Establishment at Malvern, which is where he met Ryle.

Returning to Cambridge in 1946, he graduated two years later and immediately joined Ryle’s research group at the Cavendish laboratory as a research student. After obtaining his PhD in 1952 on the fluctuations of galactic radio waves, Hewish became a research fellow at Gonville and Caius College, and then, in 1961, transferred to Churchill College as director of studies in physics.

He became a university lecturer in 1961, reader in 1969, and professor of radio astronomy in 1971, until his retirement in 1989, when he was made emeritus professor at Cambridge. When Ryle became ill in 1977, Hewish took on the leadership of the Cambridge radio astronomy group and was head of the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory from 1982 to 1988.

The award of the Nobel prize to Hewish and Ryle was immediately controversial, criticised by, among others, Fred Hoyle and Thomas Gold, for the exclusion of Bell, later Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell.

Hewish was undoubtedly the major player in the work that led to the discovery, inventing the scintillation technique in 1952, leading the team that built the array and made the discovery, and providing the interpretation as due to a white dwarf or neutron star. Bell herself was gracious about the matter, saying: “I believe it would demean Nobel prizes if they were awarded to research students, except in very exceptional cases, and I do not believe this is one of them.”

After the discovery of pulsars, Hewish continued his work on interplanetary scintillations, and the mapping of the solar wind and the “interplanetary weather”, which can have a dramatic effect on terrestrial communications.

As well as being an honorary member of numerous foreign academies, he was made a fellow of the Royal Society in 1968, and received the Eddington medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1969 and the Hughes medal of the Royal Society in 1977. A shy, modest man, Hewish declined offers to become master of a Cambridge college.

He believed that science and religion were complementary, and that: “We should be prepared to accept that the deepest aspects of our existence go beyond our commonsense understanding.”

Antony married Marjorie Richards in 1950 and they had a son, Nicholas, and a daughter, Jennifer, who died in 2004.

Marjorie and Nicholas survive him, as do five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion