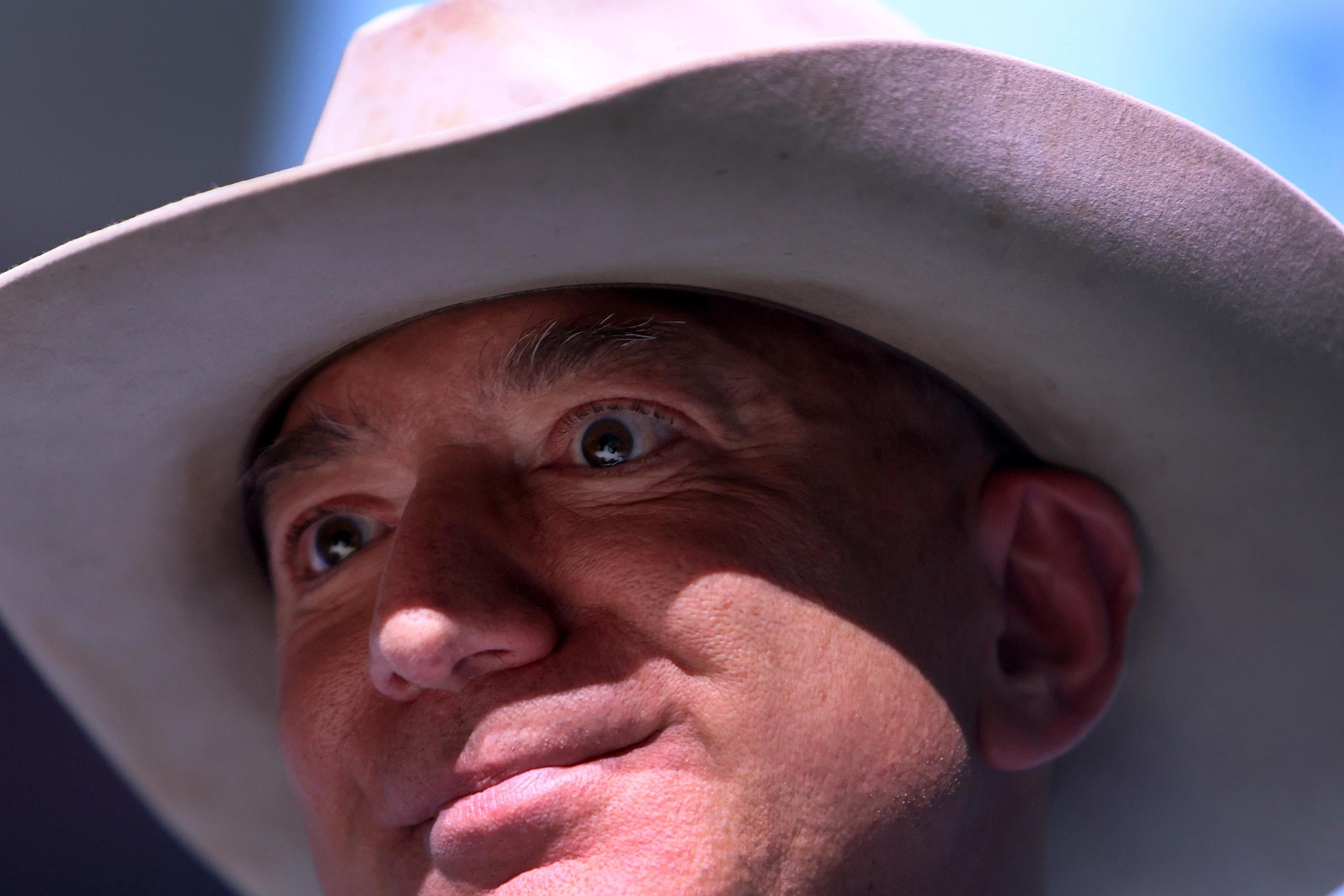

Billionaires have been paying to go to space for more than two decades, since entrepreneur Dennis Tito spent a reported $20 million on a ticket to the International Space Station in 2001. But this year, the moneyed class began leaving the planet at a rapidly accelerating pace. Two rocket company founders, Blue Origin’s Jeff Bezos and Virgin Galactic’s Richard Branson, both took brief first trips above the atmosphere this summer in their companies’ respective vessels, and defense contractor Jared Isaacman went to orbit for three days in September aboard one of Elon Musk’s SpaceX Dragon capsules. Star Trek actor William Shatner, who flew via Blue Origin in the fall, is not a member of the billionaire’s club, with a net worth of only an estimated $100 million. According to Blue Origin, the former Captain Kirk flew for free.

All of these private companies include the ceremonial presentation of “astronaut wings” to their passengers, at no extra charge, but handing out astronaut status for a simple sales transaction feels wrong. Historically, astronauts have been considered role models and heroes. They’re highly trained, physically and mentally fit, and voluntarily putting themselves in potential harm’s way in order to explore, experiment, and bring back new knowledge for all. Should the billionaires and their fellow passengers get to claim that title? The Federal Aviation Administration says, not necessarily. To qualify as a nongovernmental “commercial astronaut,” the FAA requires that you do more than just get a ticket and take the ride. According to a directive issued in July, an astronaut must do things during the flight that contribute either to public safety in general or to the specific safety of others in space. The FAA seems to be indirectly endorsing a growing backlash against all of this net worth above the stratosphere.

But you don’t have to take the FAA’s word for it. The foundational work that established international law in space seems to agree. According to the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, astronauts are to be considered “envoys of mankind.” Despite the lack of inclusive language, it reads like an endorsement on behalf of a certain kind of “Right Stuff” as a must for any wannabe astronauts. This document, which some people who work in space science call “our constitution,” leaves the door open to the possibility that the title can be earned, though not bought. It also assigns certain rights and, more importantly, responsibilities, to those with the wings. In fact, given the special missions that the Outer Space Treaty (and other foundational documents like it) gives to astronauts, we might want as many people as possible to carry that title, especially if they are already well resourced.

The Outer Space Treaty was forged during the heat of the Cold War and the Space Race, when it was still unclear who might make it to the moon first. Signatories including the United States and the Soviet Union hoped the treaty would set the terms of engagement. Space is an environment that presents tremendous dangers to human life—as professionals working in space science still remind one another, “space is hard”—and the rival superpowers realized that once they were up there, everyone would be in it together. Therefore, the terms set by the Outer Space Treaty uphold mutual aid, cooperation, and common interest. This is all while agreeing that no nation would make sovereign claims on territory, or conduct most kinds of military activity, in space.

The appropriate response to mutual danger is to remain responsible for one another. If a person in space is aware of a hazardous situation that might affect other people in space, they are obligated to contact them and warn them about it. And if you and I are both in space, and I am aware that you need any kind of help that I can offer, I am required by the treaty to render aid to you in that case. I have a responsibility to return you to your home base, or even back to your home country if needed. These practices are derived from those developed on the high seas, but these values and obligations are now enshrined in international law. Some legal scholars even argue that the terms of the treaty have entered into “customary” status, such that if any nation, even one who is not a signatory, violated them, they could be brought before an international court like The Hague.

I am not a space lawyer, but I’ve talked with enough of them to know that language matters in law. In a key portion of the treaty, this language is used: “In carrying on activities in outer space and on celestial bodies, the astronauts of one State Party shall render all possible assistance to the astronauts of other States Parties.” This is as close as the treaty comes to defining the word astronaut, and the definition seems to rely on a kind of reciprocity. A person who is carrying on activities in outer space is a person who is obligated to help others doing the same, and in that situation of mutual concern among deadly circumstances, all involved are worthy of receiving help, and worthy of offering it. Therefore they are astronauts.

Buried in the weeds of paperwork and legal language here is a kind of path to utopia via bureaucracy. The FAA’s requirement that commercial astronauts must contribute to the safety of either those in space or to the public at large echoes the reciprocal obligations in the Outer Space Treaty. With the great opportunity of going to space comes great responsibility. Where the Outer Space Treaty seems to limit that responsibility to those above the atmosphere, the language in the FAA’s directive about general public safety brings it back to ground. It reads like a nod to the treaty’s call elsewhere for the benefits of space exploration to be shared by everyone. We all need assistance sometimes, and the public on Earth is, after all, already also in space.

When American businessman Jared Isaacman went to space this year, he brought along some people in his SpaceX Dragon capsule who weren’t billionaires like him. He organized his trip, named Inspiration4, around the idea that the other “spaceflight participants” would all inspire others in some way to work towards a future in space. They included an Air Force veteran, Chris Sembroski, who received his ticket indirectly via lottery; a former astronaut candidate, Sian Proctor, turned artist and science communicator; and a bone cancer survivor, Hayley Arceneaux, who is now a physician assistant at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, where she had been a patient as a child. While in orbit, the crew conducted research on space medicine (that will help protect future astronauts). Isaacman’s mission was also a fundraiser for St. Jude’s, to which he personally pledged $100 million, some 4 percent of his then estimated $2.4 billion net worth. This is certainly good for publicity, but it’s also clearly good for the public.

Isaacson and his mission with Inspiration4 represent a choice that could be made for all future private spaceflight. And that choice is much more complicated than seemingly simple questions about whether billionaires get to go to space, or who should qualify to claim the hallowed title of astronaut. Isaacson and others with ample resources should be encouraged to visit space, and to carry on activities while there that benefit humanity, in space and on Earth, in order to live up to the ideals written into the Outer Space Treaty. And to fulfill the letter of the FAA directive, that process of providing benefit should be quantified and formalized somehow. We should ask “What needs to be done?” and find a way to get these would-be private astronauts to help do it. It doesn’t so much matter who you are, or what people call you. When you are a person who is in space, it matters what you do with your time there.

Everyone in outer space is an “envoy” of humankind, billionaire or not, they represent us at our best. So in order to actually be an astronaut, they should act accordingly.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.