Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Despite numerous calls from astronomers to rename its powerful new telescope, NASA officials stood by the naming of the James Webb Space Telescope before its launch.

With the telescope nearly a year into its stint in space, the agency has released its chief historian’s investigation into the namesake of the telescope. James Webb, NASA’s second-ever administrator, worked at the US State Department during the Lavender Scare, a period in which LGBTQ federal employees were often fired or forced to resign, and the decision to name the telescope for him courted criticism from researchers.

There’s no evidence that proves Webb was directly involved in those firings in the 1950s or in the 1963 firing of gay NASA employee Clifford Norton, according to Brian Odom, the NASA historian who completed the investigation.

Webb’s name caused controversy

Officials at NASA announced in 2002 that the telescope would be named for Webb, who oversaw the Apollo moon landing program in the 1960s and helped burnish the fledgling agency’s reputation. It was considered an unusual choice at the time, since Webb was an administrator and not a scientist.

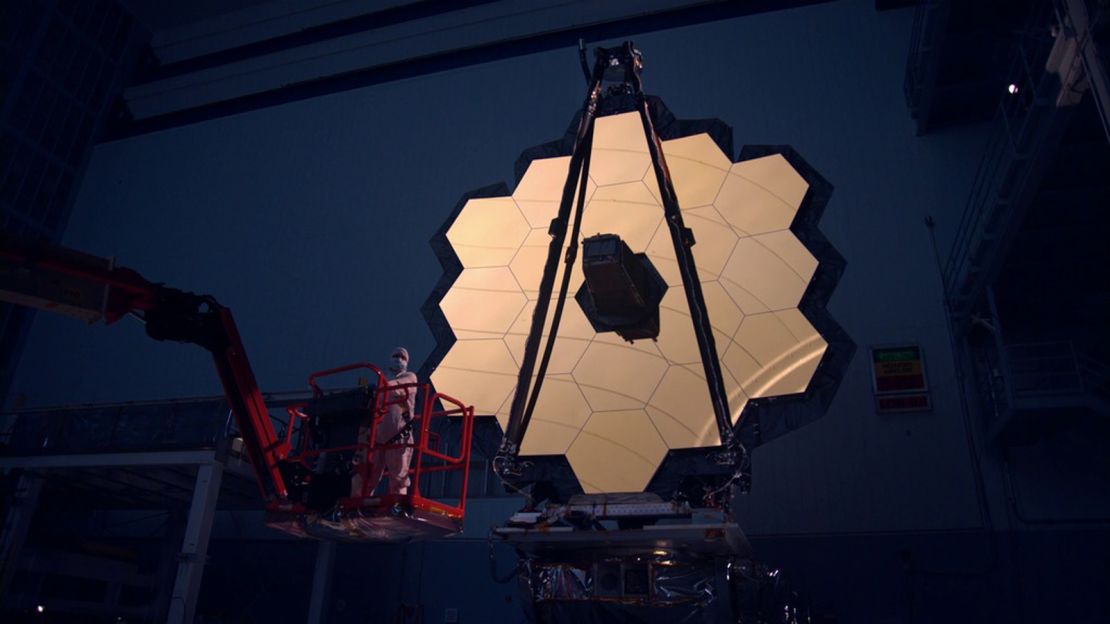

Months before the telescope was set to finally launch, though, several astronomers called on NASA to remove Webb’s name from the telescope, which has since recorded several never-before-seen images of the universe.

In a 2021 piece for Scientific American, a group of astronomers wrote that Webb’s legacy “at best is complicated and at worst reflects complicity in homophobic discrimination in the federal government.”

Even scientists who work on the telescope have expressed their dissatisfaction with its name. Earlier this summer, Dr. Jane Rigby, the operations project scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope, tweeted that “a transformative telescope should have a name that stands for discovery and inclusion.”

Officials at NASA have refused to rename it, though, citing an investigation into Webb’s career. The results of that investigation weren’t made public until now, almost a year after the telescope launched.

The report found no evidence linking Webb to firings

In his report on his investigation into Webb, Odom acknowledged the pain caused by the Lavender Scare but said that “no available evidence directly links Webb to any actions or follow-up related to the firing of individuals for their sexual orientation.”

The findings of that investigation, Odom wrote, were based on more than 50,000 pages of historical documents from various archives, including NASA headquarters, the Truman Presidential Library and the National Archives.

Odom investigated two meetings that predated Webb’s time at NASA: In 1950, then-undersecretary Webb met with President Harry S. Truman and later two White House aides and Democratic Sen. Clyde Hoey of North Carolina to discuss the Hoey Committee, a Senate subcommittee created to investigate how many LGBTQ people worked for the federal government and whether they were “security risks.”

In his meeting with Truman, Webb discussed with the president how the committee and the White House “might ‘work together on the homosexual investigation,’” according to historian David K. Johnson, author of “The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government,” one of the many documents Odom cites in his report.

No evidence links Webb to any action that followed those discussions, Odom said.

The historian also investigated the firing of Norton, a budget analyst at the space agency. Norton sued the Civil Service Commission after his firing, and his case, Norton v. Macy, was one of several that helped overturn the executive order that allowed federal agencies to fire LGBTQ employees for their sexuality, Odom wrote.

Odom said he found no evidence to show that Webb was aware of Norton’s firing; since it was federal policy at the time to oust LGBTQ employees, Odom wrote, Norton’s departure was “highly likely — though sadly — considered unexceptional.”

No documents could prove that Webb was directly linked to firings of LGBTQ employees, Odom said.