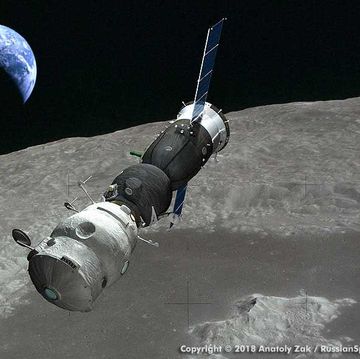

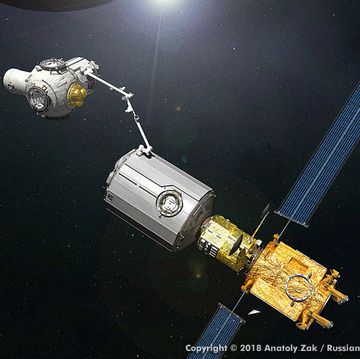

A quarter-century after the Soviet space program dropped its thick veil of secrecy, many fascinating details about the enormous scope of the USSR's space ambitions are still trickling in. The latest treasure trove of information quietly made public reveals what might have been the earliest Soviet proposal to permanently colonize the moon.

Conceived in 1967 at the height of the Moon Race with the United States, the bold plan was developed inside the same think tank that had launched Sputnik and put the first man into space. Not surprisingly, they dreamed up an innovative and ambitious plan to put people on the lunar surface to stay.

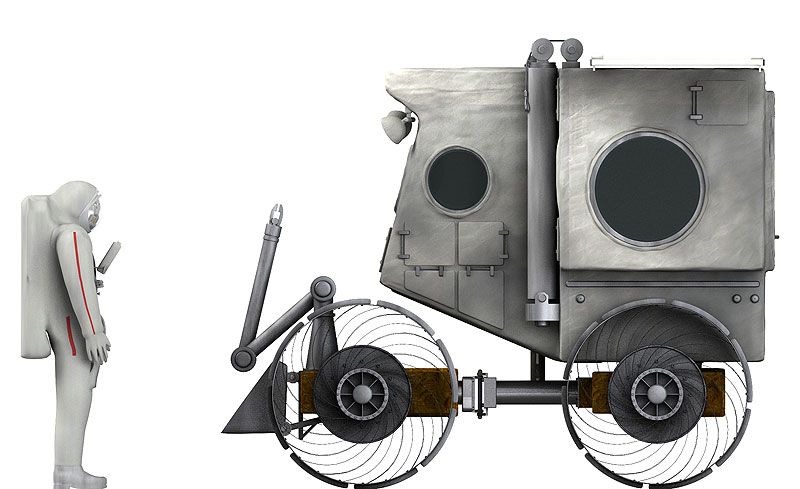

The Soviet engineers hoped to start building their lunar outpost with the delivery of the multipurpose Lunar Engineering Machine, LIM. The three-ton rover would be used for soil-moving operations and scouting, cargo hauling, and it would also double as a crane and a mobile drilling rig. A telescope-like crane and a drill would be attached to the sides of the cockpit. The rover would be also equipped with external lighting, TV cameras, and windows.

To propel the exotic vehicle, the Soviets developed a four-cylinder internal combustion engine, but with a twist. Unlike traditional motors, it would burn self-igniting rocket propellant, mixing liquid fuel with oxidizer. Vacuum valves would be used to vent combustion products out of the engine's hermetically sealed housing. One engine would be enough to propel the vehicle, but when LIM was faced with difficult terrain, it could activate both motors and turn on all-wheel drive. Wheels of the machine were designed to be flexible to do away with a complicated suspension system.

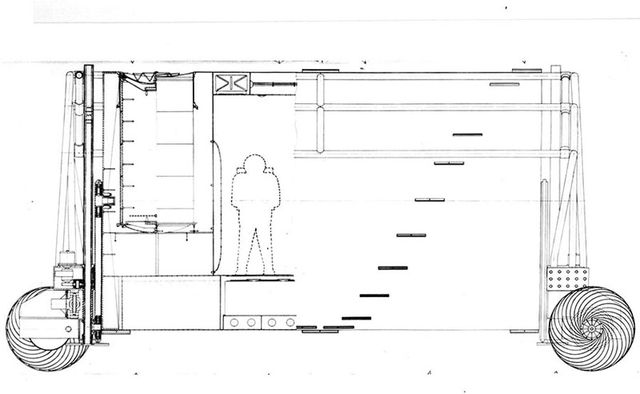

The boxy rover would also feature two self-propelled platforms with their own propellant tanks and pairs of wheels linked by a transmission system, which would allow each platform to bank and tilt independently. The front platform would sport robotic arms and a plow, while the rear platform would carry a pressurized cabin for a single driver wearing no spacesuit. Under emergency conditions, a second person could squeeze into the back, though If necessary the rover could operate unmanned under remote control from the lunar base or even from the Earth.

Self-Burying Habitat

The rover needed all this moon-moving equipment because it would play a crucial role in making the moon base livable: Specifically, getting the pre-fabricated habitation modules of the base below the lunar surface to provide reliable radiation shielding so that its inhabitants could survive.

According to one scenario Russian engineers imagined, a pair of rovers was to be delivered to the Moon along with a 10-meter habitat. Subdivided into two floors, the habitation module could house from three to six people. Initial provisions and supplies carried onboard the spacecraft would sustain a crew of three for at least three months.

Relying on the data from the American Surveyor-3 probe, which landed on the Moon on April 20, 1967, Soviet engineers banked on the fact that the lunar soil would likely have a consistency of soft sand and would not require grinding before its application as a radiation shield. As a result, their plan suggested that one rover would bulldoze the soil toward the base and another would use a specially built sand-thrower to cover the habitat. A deployable net cage around the module would be used to keep the soil shield in place.

For any areas with harder surface, the Russians had the idea to use a cutting tool attached to the rover to carve 255 square blocks out of soil, which would then be used to build a protective wall around the future settlement. The hole in the ground formed in the process of making the blocks would be used as the bed of the radiation shelter.

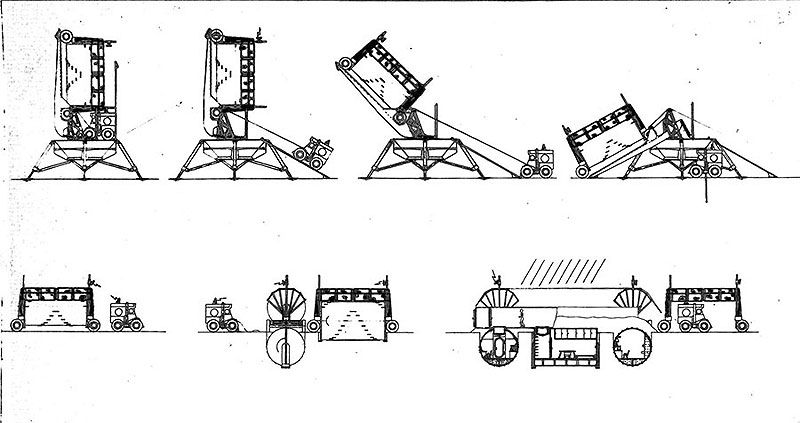

But the most exotic plan they proposed envisioned a self-propelled, self-burying habitation module. The six-meter long, 3.6-meter-wide cylinder would be fully equipped for up to six cosmonauts to work inside it. After arrival to the Moon, the module would be unloaded from its landing platform along with a self-propelled four-wheel trailer. Once in horizontal position, the entire contraption would then embark on a journey across the lunar surface with a speed of up to six kilometers per hour, in search of a site with soil soft enough for "self-burial."

At the right location, the trailer would activate an electrically driven revolving mechanism, which would begin rotating the cylindrical module around its main horizontal axis. Blades arranged in a spiral on the module's exterior begin cutting into the soil and throw it out. Sliding down along the guide rails of the trailer, the giant cylinder would slowly sink into the newly forming trench. Upon reaching the right depth, mission control would need to ensure that the module stopped spinning with its ceiling facing up. Once that is done, a telescopic airlock would extend from the module to provide an access for the crew from the lunar surface. Designers estimated that it would take the module around 4.3 hours to completely bury itself in sandy soil.

Soviet engineers went into trouble to detail the entire process of unloading the module from the landing platform, building the shelter and developing crucial components of the LIM rover, such as its exotic engine and its transmission system. All for naught, though, as the USSR eventually put small rovers on the lunar surface, but never cosmonauts.

Although the ambitious Soviet plans for a lunar base had never materialized, the latest revelations provide a rare glimpse at the plans that Russian engineers had up their sleeves had their efforts to build a Moon rocket succeed in the 1960s. It also provides plenty of inspiration for the future.

Anatoly Zak is the publisher of RussianSpaceWeb.com and the author of Russia in Space: the Past Explained, the Future Explored.