Water inside the moon mostly came from asteroids that smashed into the lunar body more than four billion years ago, with comets adding less than previously thought, scientists say.

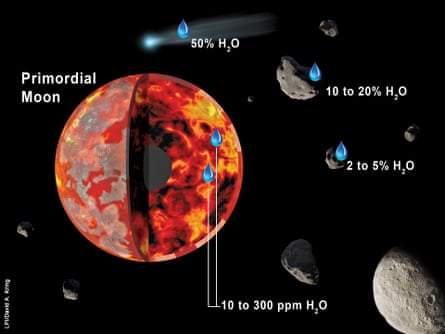

Composed of material ejected when a large, Mars-sized body ploughed into Earth around 4.5 billion years ago, the moon was long thought to be bone-dry. But research has shown that traces of water exist both on the surface and inside.

Now scientists say they have pinned down where the moon’s inner water came from: objects that crashed into a vast magma ocean thought to have existed on the moon early in its history. “We believe that asteroids delivered the majority of water to the moon and comets delivered very little - they weren’t major players in the first few hundred million years of inner solar system history,” said Jessica Barnes, a planetary scientist at the Open University, who co-authored the research.

Writing in the journal Nature Communications, a team of scientists from the UK, US and France reveal how they sought to unpick the origins of water inside the moon by looking at ratios of hydrogen to deuterium, or “heavy hydrogen”, in lunar samples brought back by the Apollo missions. They compared these isotope ratios with those known for comets, a range of primitive meteorites called chondrites, and other objects in the solar system - including Earth.

“[The hydrogen isotopes are] like a fingerprint or a barcode for where water may have come from in the solar system - these different types of objects have different hydrogen isotope compositions,” said Barnes. While comets, which form far out in the solar system, carry water rich in deuterium, water formed nearer the sun is richer in hydrogen.

The team also considered the amount of water comets and different types of asteroid could bring and the amount and type of nitrogen these objects would deliver, as well as levels of “metal-loving” elements in lunar samples, to unravel the contribution of each object towards the moon’s makeup .

The authors say their calculations reveal that less than 20% of water inside the moon arrived from comets, with the bulk coming from asteroids that crashed into the lunar magma ocean during a period of 10 to 200 million years. These asteroids, they add, were similar in makeup to a type of water-rich primitive meteorites known as carbonaceous chondrites. The formation of a lid, or crust, over the magma ocean prevented the water and other volatile substances from escaping, says Barnes.

But the authors admit there are still many unknowns. “I think the jury is still out on how much water could have come from the proto-Earth,” said Barnes.

It has also previously been suggested that the water inside the moon could have come from the early Earth following the great collision, with the Earth’s water delivered by asteroids - an idea supported by the moon and the Earth having almost identical hydrogen isotope “fingerprints”.

But the new research only explores the possibility that up to a quarter of the water inside the moon could have come from ancient Earth. That, says Barnes, is because it is doubtful that water could survive the processes involved in the formation of the moon and keep the same ratio of hydrogen isotopes.

Rather, she says, the similarity between the hydrogen isotope ratios of the Earth and the moon is likely to be down to wet asteroids delivering water to both.

Not everyone is convinced that the riddle of the moon’s water has been solved. “They are doing the best they can with the information that we have, but I think that this is not the last that we will hear about this, because we have significant uncertainties,” said Alberto Saal of Brown University, who has authored key research on the presence of water inside the moon.

Among his qualms is the fact that the makeup of comets is still poorly understood, while a range of processes that could change the ratio of hydrogen isotopes in the lunar rocks and other objects also merit further study.

Barnes agrees that the understanding of such processes is limited and believes a host of models are needed to better understand what would have happened to water inherited from Earth during the formation of the Moon.

What’s more, only 2% of lunar samples brought back by the Apollo missions have been studied for their water content so far - and all of them come from the near side of the moon. “We are completely restricted geographically about what we can understand about the entire planetary body,” said Barnes.

But, she adds, a new wave of lunar missions could change that. “It is a really exciting time because there are all these new missions that plan to go to the moon, go to the poles, which could help us further pin down this story as well as helping us understand the surface water as well,” she said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion