A leading space scientist has accused the European Space Agency of having a “problem with promoting women” that has led to men holding almost every top job at the agency.

Rita Schulz, who was the lead scientist on the Rosetta comet-chasing mission from 2007 to 2013, also told the Guardian that she had been “shafted” by management when she was dropped from the historic project six months before its culmination.

The German scientist, who was ESA’s first and only female project scientist at the time, said she felt compelled to highlight gender bias after seeing so few women rising up the ranks during the past two decades.

“This is something that is not good at ESA,” she said. “Women are never promoted. I have to say I believe this is a problem.”

Schulz was hired as deputy project scientist on Rosetta in 1996 and said she expected many other women to follow. But by the time she was replaced as project scientist by Matt Taylor, in 2013, she remained ESA’s only woman in leadership on an active mission.

“I was the only one for 20 years, sitting in the room with all these men,” she said. “I really think there should be more.”

Schulz said she was not given an explanation for why she was moved off Rosetta after 17 years – and is not suggesting sexism played a part. But leaving the mission unexpectedly just before its climax had been “tremendously damaging” for her career, she said.

“It took me a long time to get over it,” she said. “I was shafted.”

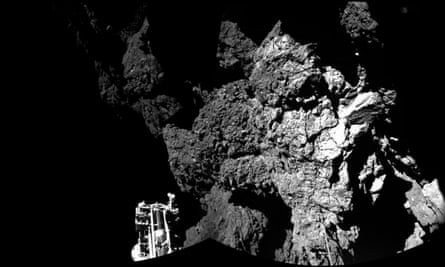

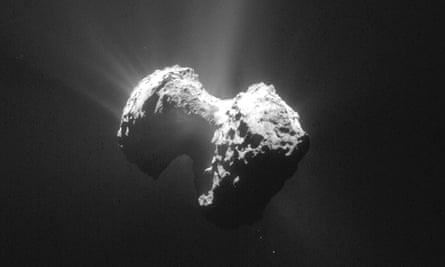

Schulz left six months before the Rosetta spacecraft “woke up” after spending nearly three years in hibernation mode and a little over a year before the Philae lander made its dramatic descent onto the duck-shaped comet’s surface.

When Rosetta sent its “phone home” signal to confirm the £1bn spacecraft had emerged intact from its dormant state nearly 500 million miles from Earth, mission scientists were seen cheering and hugging in celebration that Europe’s audacious mission was on track.

Schulz watched her former colleagues from her living room on her laptop after requesting and failing to get an invite to the mission control room gathering in Darmstadt. “It was not a good chapter,” she said.

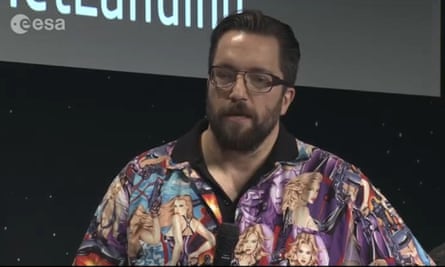

Schulz also watched from afar as her replacement, Matt Taylor, sparked controversy by wearing a garish shirt covered in pin-up style scantily-clad women during live television coverage of Philae’s comet landing.

“I don’t think he had any sexist background with that shirt,” said Schulz, adding that the management should have advised him not to wear it while addressing the world’s media.

“Matt Taylor is much too low down the food chain to make any difference to whether women are hired for top jobs,” she added. “He is not the problem. It is much more fundamental than that.”

Schulz said she has never experienced direct sexism at ESA, but felt she had to work harder to prove her worth. “As a woman, you always have to be better than the men,” she said. “I make sure in meetings that I don’t get too excited. If a man gets excited he’s determined. If a woman does, she’s emotional or hysterical.”

At times, she felt being a woman made it easier to resolve disputes when team members clashed. “Women are not alpha wolves,” she said. “They can take the sting out of a heated discussion, they can make a better joke, they don’t have to be right. Two alpha wolves can’t do that.”

Jochen Kissel, co-principal investigator on Cosima, a dust analysis instrument aboard Rosetta, until he retired in 2005, said that Schulz had to manage fierce disagreements as the mission entered its final phase.

Kissel said he is “surprised still to this day” that Schulz was taken off the project.

“Rita, in my memory, was the only woman we had leading a project,” he added. “If you go there [ESA headquarters] it’s all men, except at the reception of course where it’s always a woman.”

Schulz, who remains a scientist at the space agency, believes a first step to addressing ESA’s gender imbalance would be introducing a quota of at least two women in the science directorate, which comprises ESA’s director general and 10 directors. A woman, Magali Vaissiere, joined the directorate for the first time in 2013.

Despite no longer having a formal role on Rosetta, Schulz maintains a close interest in the mission and was first author on a Nature paper on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko last year.

In a written statement, ESA said: “ESA has a long commitment to diversity and gender equality ... As many other organisations ESA suffers from the fact that the number of women who choose to graduate and follow a career in these fields is in all European countries significantly lower than the number of men.”

Considerations of work-family balance could also contribute to fewer women applying for high-ranking positions, ESA added. “Taking also into account that a job at ESA is often linked with being expatriated to another country, this organisation of work and private life is not always easy to manage and ESA tries to support as much as possible, offering childcare facilities, support in the search of schools and flexible working patterns.”

Within the science directorate, there is now one female project scientist on a confirmed mission (the Cheops mission) and ESA cited several important female managers outside its science division.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion