In the entire history of human space travel—nearly sixty years—only 559 people have ever strapped into a spacecraft and flown off the planet. Today, NASA will announce its next batch of candidates that will potentially join their ranks, a handful selected from tens of thousands of applicants.

But over the next decade, the number to date will likely become a distant benchmark. With rapid advancement in aerospace technology and the proliferation of commercial investment, we could very well be witnessing the birth of not only a new era, but also a new type of space traveler altogether: the pure passenger.

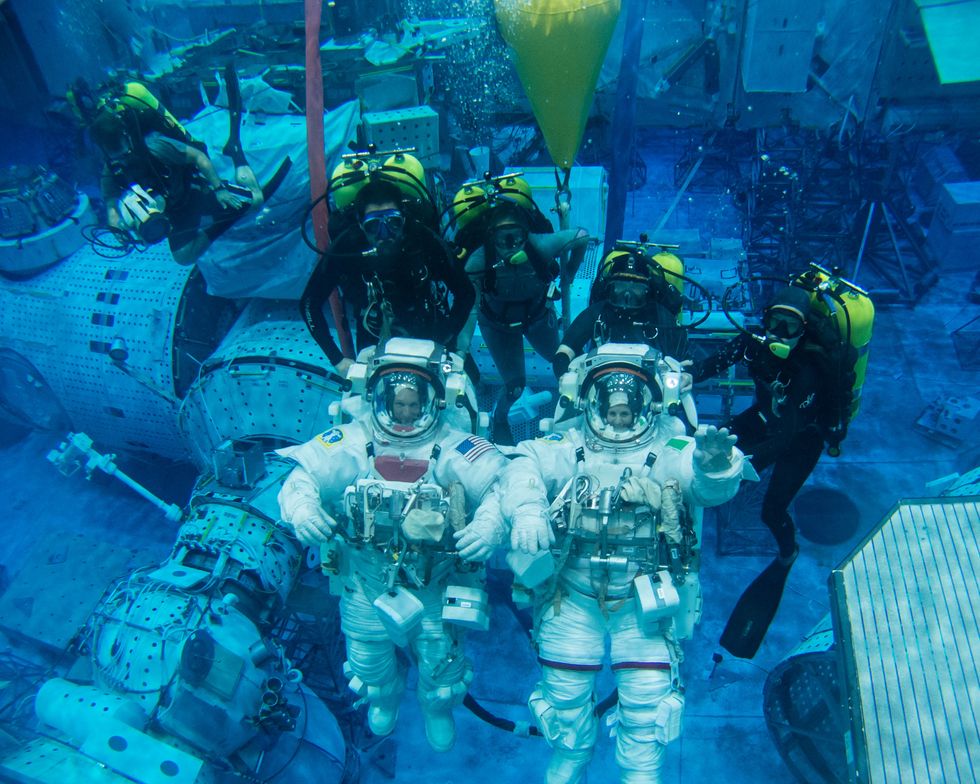

In this new day of exploration, the prerequisite for being fit to fly into the heavens no longer requires you to follow the path of the astronaut with years of training in supersonic jets, or spacesuit clad tests in an underwater replica of the International Space Station. "A few weeks before launch, [the astronauts] actually take final exams," an official from NASA's Office of Public Affairs says.

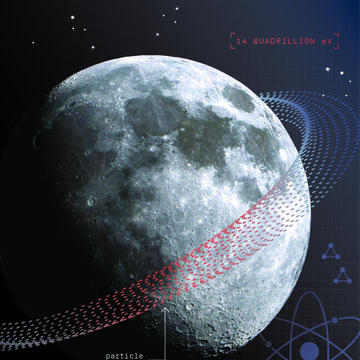

As soon as 2018, however, SpaceX hopes to launch its Dragon capsule around the moon with two wealthy private citizens at the helm, undertaking a trip the likes of which hasn't been seen since the Apollo missions. Companies like Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic plan to offer jaunts the nearer reaches of space, and the Russian space agency has ferried tourists to the ISS, but sending civilians beyond orbit is new territory.

In addition to the hefty deposit required when booking that trip, there will undoubtedly be mental and physical training to complete before the week-long excursion around the dark side of the moon. But now that craft can fly themselves, piloting skill is no longer a mandatory requirement.

Except, perhaps, in the case of an emergency. How well will this new breed of extraterrestrial traveler be prepared for such an event? It's hard to know in the case of SpaceX and this most ambitious private spaceflight yet. The company did not respond to a request for details on its training measures, which means we can only make an educated guess.

My Body Is Ready

"The fact of the matter is that anybody can actually go to space." says Constantine Tsang, a planetary scientist at the Colorado-based Southwest Research Institute that led the New Horizons mission to Pluto in 2015. Tsang himself is one of those people. Usually hunched over his desk analyzing data from ground-based telescopes, he's also been training to fly on a commercial spaceplane for nearly seven years, waiting for the tech to catch up.

The base requirement for just being in space is essentially just surviving the two gravitational environments that humans encounter during spaceflight. The main attraction is the microgravity of the void, but on either side are bouts of high-g force that pushes on your chest on your way there and back. Any space traveler—trained astronaut of the most passive of passengers—has to train for both.

You can get a brief taste of zero-g on a rollercoaster or jumping out of an airplane, but the way to simulate it at length and without an abundance of rushing air is by flying in specially designed airliners that go through parabolic maneuvers, aka "the vomit comet."

"What happens is the plane dives," explains Tsang as he demonstrates the arcing flight pattern with his hands, "you do a whole bunch of these loops and parabolas. You can angle it to mimic either zero-g, lunar gravity, or Martian gravity depending on what you're trying to achieve."

It's one thing to understand zero-g, but another to feel it. As your vestibular system—charged with matters of balance and spatial orientation—tries to make sense of such an unnatural situation, the signals being sent from your inner ear to your brain contradict what you see. This mismatch has a common physiological response: Something is wrong! Better puke! Prior experience in zero-g definitely helps, but the sensations are always kind of stressful. According to NASA, even its own astronauts who are properly trained still encounter occasional bouts of space sickness.

During liftoff and reentry is the opposite and more directly dangerous condition: high-g. World-renowned human performance experts like Michael J. Joyner of the Mayo Clinic have spent years researching the health effects of space exposure, leading to the development of NASA's Human Research Program.

Due to the vertical trajectory and acceleration during liftoff, you'll experience roughly four gs of centrifugal force. According to Joyner, the main concern during those conditions is blood pooling in your lower extremities, in turn "suffocating" your brain and leading to loss of consciousness. During reentry, those g forces can go up to nearly seven times normal gravitational force, and because of the change in your flight trajectory when coming back to Earth, the gravity creates an incredible amount of weight pushing into your chest, so it becomes very hard to breathe.

To train for high-g conditions, NASA astronauts do things like strap into centrifuges in their spacesuits to get spun around and fly in supersonic fighter jets "pulling gs" for hours. It's not just to get used to the sensation. The training helps passengers strengthen their lower abdomens and learn how to breathe without passing out under the stress. "You'll want to do a bunch of that training," says Tsang, "because as you ride up, you want to enjoy that sensation."

The stresses of pulling gs and then being weightless are both well-known and unavoidable, so it seems reasonable to assume SpaceX's training regimen will mirror NASA's pretty closely. Retired astronaut Charlie Walker—a former engineer and veteran of three Space Shuttle missions from 1984 to '85 and the first commercial astronaut to fly with NASA—agrees that the most daunting aspect of spaceflight for anyone will be the sheer magnitude of the physics at work.

"You have to be ready, not only to ride out that rocket," explains Walker, "but at the end of it, to occupy that spacecraft and do what's necessary for the mission. I do think it takes a certain mindset and a certain kind of individual."

That "mission" is where the prep-paths of traditional astronauts and pure passengers are likely to diverge. All that the passengers on SpaceX's little moon trip will likely need to do after liftoff is sit back and enjoy the ride as the Dragon capsule flies itself.

Zero-G MacGyver

To survive astronaut technical training, it helps to love engineering. A lot of Walker's time training in NASA's Space Shuttle program was spent getting acquainted with the shuttle's extensive array of equipment and subsystems.

"I was familiar, but not technician-grade. Qualified to MacGyver any of the systems," Walker says of the Space Shuttle. "The intent was, with me accompanying six NASA astronauts, they would do most of the repair work. But if I needed to support them, I needed to be calm and cool."

Mitigating surprise is a common theme in NASA's training program, says Walker, who learned the ins and outs of everything from booster fuel to the on-board microwave. It seems unlikely that the pair of SpaceX travelers will have anything approaching that level of knowledge, which takes years of hard work and serious smarts to achieve. Since SpaceX's Dragon is designed to be completely autonomous, the passengers on board may only know as much about the inner workings of the propulsion system as you know about the internals of your DVR.

There's still specific expertise necessary for pilots and passengers alike. "Your suit becomes a significant life-support system," says Walker. "An individual can put that suit on by themselves, but you run the risk of missing a complete tight seal here or there. So it's much better to have a buddy. And you have to be ready to do that in zero gravity." If worse comes to worst, a few seconds off your average time could save your life.

It's not always that high stakes. "Your first serious attempt at going to the bathroom in space is in space," says Walker with a laugh. "So you have to have an attitude which is 'This is probably going to be messy, but here I am in a place where few people have gone and I'll deal with it.'" The logistics could be especially challenging since the Dragon capsule does not have a dedicated bathroom.

There's no way great to practice for that dirty job or a number of other zero-g contingencies here on Earth. In these cases, a spacefarer's best weapon against the unknown is pure knowledge. If everything goes to plan, a passenger's 101-level understanding of all things space should be more than enough. A true astronaut's encyclopedic knowledge is overkill on a self-flying craft. Unless, of course, it's not.

The blackness beyond orbit

Space tourism of the low-orbit variety has been in the cards for years, but when SpaceX announced its intention to launch two private individuals into space on a 500,000-mile trajectory around the moon back in February, it opened a whole new can of worms.

Far outside orbit, the effects of cosmic radiation come into play, as well as the risk of fatal decompression if you're directly subjected to space beyond the elevation known as the Armstrong Limit. But most notably, outside of our planet's orbit, 'back toward Earth' ceases to be the default direction an object tends to travel. The Dragon capsule's self-driving should save its passengers from having to worry about this too much. But in the case of contingency, stakes are high, and traditional astronauts spend years of full-time training to prepare for them.

"If you're grabbing a yoke that's going to guide you through a one-half degree corridor in the upper atmosphere at 24,000 miles per hour, and if you go too low, you vaporize, too high you skip off the top of the Earth never to be seen again—that takes piloting skills," says Walker. To reach anywhere near the same sort of preparedness, citizen passengers would have to train those skills up from scratch in far less time, and likely with far less natural aptitude.

SpaceX currently boasts a 94 percent success rate when it comes to launching its family of Falcon rockets and has somewhat mastered the ability to land its first-stage booster. These are impressive feats of precision that bode well for the Dragon capsule and the Falcon Heavy rocket that SpaceX wants to carry people to the moon and beyond. The technology of space travel—and of the world in general—has improved exponentially since mankind's last spin around ol' Luna.

But it's also been a long, arduous road for the ambitious aerospace manufacturer, and the upcoming moon mission may be its most formidable challenge yet. Assuming there are no major changes to the plan, it will be the maiden crewed voyage for the company's Dragon capsule, the first crewed mission driven entirely by autopilot, and one of the first feats of the Falcon Heavy rocket which SpaceX says "will be the most powerful vehicle to reach orbit." And aboard it, a crew not of professional, career astronauts, but rather of wealthy passengers.

Without specifics from SpaceX itself—or firsthand accounts—it's impossible to know how rigorous their training will be. We also don't know the identity of the passengers, and they might just turn out to be jet pilots or astronauts by happenstance, though it's unlikely considering the cost of the tickets. What is for sure, however, is that as this new breed of spacefarer evolves, it will be crucial to make sure they're prepared for the trials of the void, if perhaps not quite as prepared as the pioneers who flew before.