The rasp of the filling cabinet’s shutter fills the office, and my guest comes face to face with his past. “My pharaoh’s tomb is open,” he quips, before uttering a more heartfelt, “My goodness me.”

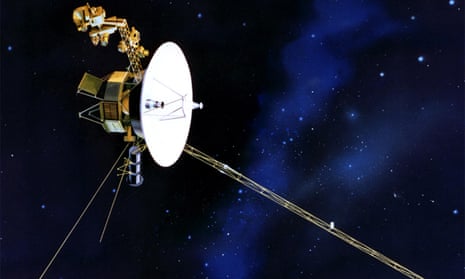

His name is Garry Hunt and we are standing in front of more than 80,000 postcard-sized photographs of the outer solar system. They were taken by a pair of Nasa spacecraft, Voyager 1 and 2, that launched 40 years ago this summer.

Although Hunt now describes himself as a “golfer extraordinaire” back in the day he was an atmospheric physicist and the man responsible for the camera system that took these images.

He was the only senior British researcher associated with the mission. His success in that role not only helped change the way we saw Earth’s place in the universe, but also opened the way for the UK to become a global player in planetary exploration.

The Voyagers returned the first detailed pictures of the four giant planets in the outer solar system: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. Each one of these planets is between five and eleven times the diameter of Earth. They have no solid surfaces, but incredible weather systems that encircle the globes in colourful cloud belts and giant hurricane-like storms.

The Voyagers showed them as remarkably alien places that even now hold clues to the way our own Earth formed more than 4.5 billion years ago. They also revealed that Jupiter’s moon Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system, and gave the first hints that another moon, Europa, contains a global ocean that may harbour life.

“It’s marvellous to think this archive is still here and still being used. Being involved so long ago – we started the mission 50 years ago – and this is still of interest … it’s exciting. This was a starting point and this information will be used time and time again,” says Hunt.

One thing that the photos can be used for is to compare them to more recent images. This way, scientists can look for changes in these worlds that hint at unseen processes taking place below their surfaces.

We are being hosted in this trip down memory lane by Carl Murray, professor of mathematics and astronomy at Queen Mary University of London, where the archive is located. Back in August 1977, when the first Voyager spacecraft was launched, he had just finished his bachelor’s degree and was working the summer as a porter at a hospital in Whitechapel.

He then headed out to Cornell University, New York, to start research using these images. He still returns to them today for inspiration of what to study next. “It is like holiday snaps but showing them to friends and saying well that’s really interesting, I think I’ll make my next holiday around that,” he says.

By holiday, he means “next space mission”.

We are all here to make a retrospective programme about the missions for the BBC World Service. And while Nasa have digital copies of these images in their computers back in the US, there is undoubtedly something special about seeing the only physical collections of these images in the world. It is like seeing the crown jewels of the mission.

Back in the 70s and 80s when the spacecraft were encountering the planets, the pictures were so widely distributed that all of us will have seen them somewhere or another. “Yes, we saw the pictures on everything from chopstick boxes to posters on the underground,” says Hunt.

The interest in the images changed the way Nasa communicates its work with the public. “Voyager was the first real mission that involved the pubic, kept the public informed, the involvement with the media was phenomenal and I’m very proud that happened. I’m pleased that other missions continue to do so,” says Hunt.

Hunt himself was such a regular on Patrick Moore’s The Sky at Night television show, that he became the public face of the mission to a whole generation of UK armchair astronomers.

And it is not just the public perception of space that was changed by the Voyager images. “In those days planetary exploration was something that Nasa did and the UK didn’t really get involved in. But the fact that Garry was involved meant that other people could get involved. This has blossomed now if we think of missions like Rosetta and Cassini and the forthcoming Juice mission, all with massive UK involvement. It made us think that the UK does planets, Europe does planets – it’s not just Nasa,” says Murray.

Indeed, the United Kingdom Space Agency’s website lists 14 planetary exploration missions that the UK is working on. Most of these are through its membership of the European Space Agency. And it all started with the Voyagers.

“I think about Voyager all the time because they were the pathfinders essentially. They taught us how to send multi-instrument spacecraft to the outer solar system,” says Murray.

The Voyagers are now heading out of our solar system, bound for the stars. Perhaps whimsically, each one carries a golden record that preserves sounds and images of Earth. They were the brainchild of Carl Sagan, who also worked at Cornell University. He reasoned that should extraterrestrials find the spacecraft floating in interstellar space, they would recognise the record as a way of us saying hello, and trying to tell them something about us.

“When I worked at Cornell,” says Murray, “I realised that a lot of the images on the record were taken around upstate New York [near the university]: the local supermarket and all these places I knew. So I had this fantasy that sometime in the future when the aliens pick up the Voyager spacecraft, learn how to read the disc and come back looking for all these locations and one day the aliens will land in upstate New York.”

Perhaps they will also return the spacecraft to Earth. If they do, I think the chances of it ending up with its image library in London’s Mile End Road are slim. But then again, who would have thought such invaluable images from a Nasa mission would have ended up so far from the US in the first place?

Space 1977 airs on BBC World Service at 2pm on Sunday 20 August and is available online after that.

Stuart Clark is the author of The Search for Earth’s Twin (Quercus). He will be delivering the Guardian masterclass on Is there life beyond Earth? on 6 September 2017.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion