The Icy Secrets of an Interstellar Visitor

The mysterious space object 'Oumuamua may harbor ice under a crust hardened by cosmic radiation.

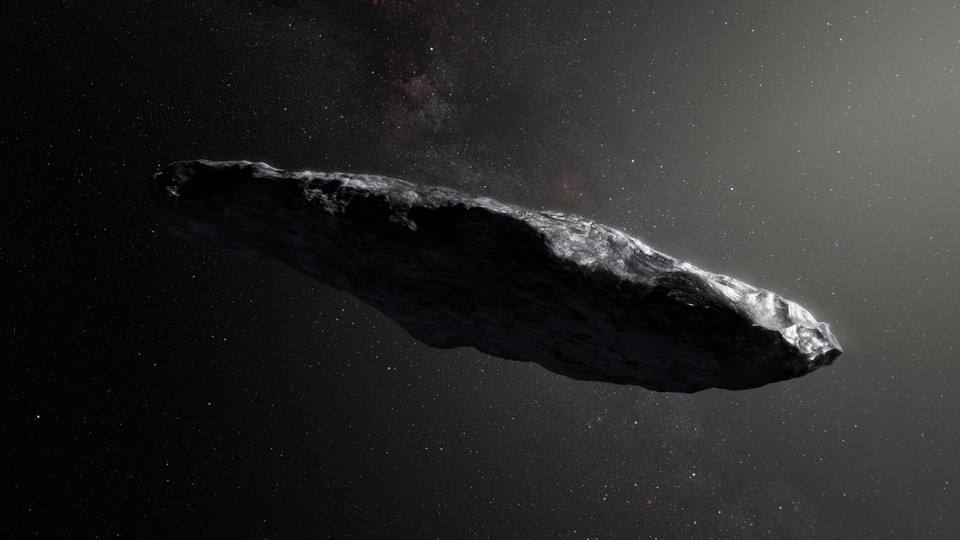

To telescopes, ‘Oumuamua, the interstellar asteroid that made itself known to Earth in October, looks like a point of light in the dark, much like a star in the night sky—a perhaps underwhelming picture of a significant discovery.

But for astronomers, the tiny speck—the sunlight reflected by the asteroid—can reveal a trove of information. They can break down the light from an object into a spectrum of individual wavelengths, from which they can infer the object’s shape, chemical composition, and other properties. As astronomers like to say, if a picture is worth a thousand words, then a spectrum is worth a thousand pictures.

The astronomy community has spent weeks sorting through these pictures of ‘Oumuamua, captured by telescopes around the world as the asteroid sped away from the sun and faded from view. The earliest analysis of the light from ‘Oumuamua, conducted by its discoverers in Hawaii, revealed a strange, fast-spinning, cigar-like object unlike anything they’ve ever seen. The latest analyses continue to produce tantalizing results, further challenging long-standing predictions for the first visitor to our solar system.

‘Oumuamua has a thick crust of carbon-rich material, hardened by years of exposure to cosmic radiation in interstellar space, that could be protecting an icy interior, according to a new analysis in Nature Astronomy of the object in visible and near-infrared wavelengths. The coating could explain why ‘Oumuamua shows no signs of being a comet, the kind of object scientists long expected would coast into our solar system.

When the asteroid was first spotted by the Pan-STARRS telescope in Hawaii, ‘Oumuamua was already speeding away from the sun and quickly fading from view. Scientists had only about two weeks to deploy telescopes to soak up the reflected light before the interstellar visitor got too far away. They looked for a coma, a stream of evaporated particles that trails comets as they pass near the sun and their icy contents become heated. ‘Oumuamua had made a fairly close pass to the sun—about a quarter of the distance between the sun and Earth—and telescopes were prepared to spot as little as a sugar cube’s worth of material flying off the object every second.

“We had data that matched pretty closely with what we’d expect for a body out there,” said Alan Fitzsimmons, an astronomer at Queen’s University Belfast who led the new analysis. “And yet we saw no sign of ice being heated and ejected into space.”

‘Oumuamua didn’t show signatures of ice or minerals found in rock, which means it’s neither icy nor rocky, at least not exactly. But it did show signs of carbon compounds. Fitzsimmons said previous studies have revealed that when carbon-rich, comet-like objects are exposed to the radiation that would be found in interstellar space, the material forms a crust that acts as insulation. If ‘Oumuamua has ice, as a comet would, it may be hiding beneath a mantle half a meter thick, formed after hundreds of millions—perhaps even billions—of years of bombardment by high-energy particles.

Fitzsimmons and his colleagues say ‘Oumuamua’s crust may have been able to prevent heat from the sun from penetrating the surface and vaporizing ice particles. According to their thermal models, any ice buried 30 centimeters (12 inches) deep would have remained intact even as the surface of the asteroid reached temperatures of about 600 degrees Kelvin (620 degrees Fahrenheit) during its pass of the sun.

“Comets are absolutely excellent insulators,” said Karen Meech, one of ‘Oumuamua’s discoverers at the University of Hawaii, who was not involved in this new analysis.“They’re very fluffy and porous, like a down jacket.”

Scientists will likely never know for sure what lies inside ‘Oumuamua. When astronomers study the light reflected from the asteroid, they’re only examining the top few microns of its surface, a width smaller than that of a human red blood cell. “We can infer only so much about these little dots of light,” said Michele Bannister, an astronomer at Queen’s University Belfast and a coauthor on the new study.

Astronomers also have a finite amount of data to work with. Most of their ground-based telescope observations were carried out in the two weeks after ‘Oumuamua was discovered, when it was still visible enough to get good measurements. The majority of research on ‘Oumuamua—the attempts to explain its weird shape, its nonstop spinning, its unexpected hardiness—will come out of this data set.

The rest may come from yet-to-be published observations by space telescopes like the Hubble, which has tracked ‘Oumuamua to help astronomers better understand its trajectory and where it came from. The asteroid is now about twice the distance between the Earth and the sun from our planet. Even to Hubble, the producer of countless, radiant images of distant stars and galaxies, ‘Oumuamua, a small object about 400 meters long, will look like a small point of light.

“It could be icy inside, and we’ll never know,” Meech said.