A new degree program at the Colorado School of Mines has opened a new frontier in the school’s expertise in natural resource extraction.

The Golden-based college’s has quietly been piloting graduate level classes for students interested in learning about mining and gathering natural resources from the moon, asteroids and elsewhere in space.

Next fall, its Center for Space Resources become home to a degree-granting program — the first of its kind and one that’s already attracting interest from around the country and world among students seeking to be pioneers of mining in space.

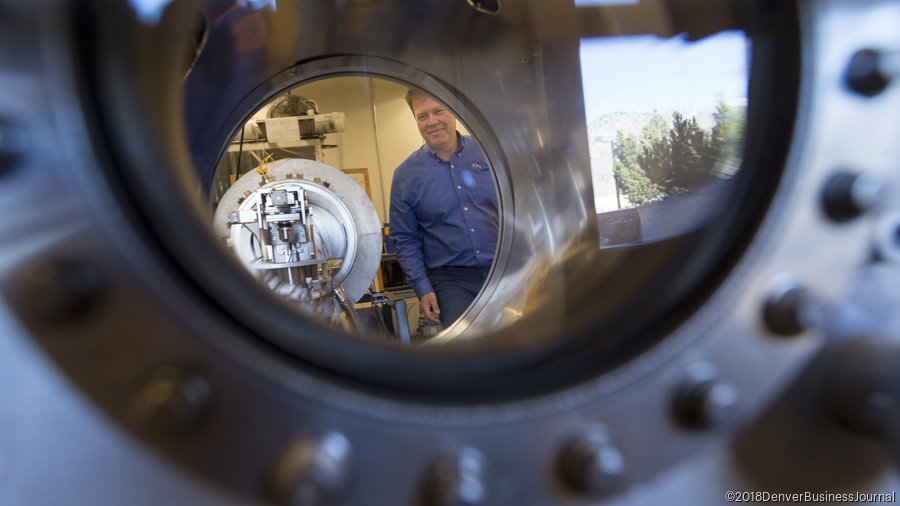

“Everything in this program is happening sooner than we expected and bigger than we expected,” said Chris Dreyer, an assistant research professor for the Center for Space Resources. Dreyer teaches the first space mining course in the world from his office desk at the School of Mines, looking on his computer screen at students logged in for discussions from three continents.

The program had a handful of students who took a pilot class last semester, called “Introduction to Space Resources,” offered via online video conference, said Angel Abbud-Madrid, director and founder of the Center for Space Resources.

Now, 35 students are taking two courses the program offers this semester. The program has added George Sowers, a former executive and scientist from United Launch Alliance, the Centennial-based rocket launch business, as its newest faculty professor.

The program's students so far have been from outside Golden, scattered around the United States. One is from Hong Kong, where class starts early in the morning. Three others are in Europe, where class starts 1:30 a.m. local time.

The graduate degrees in Space Resources will require students to enroll in electives rounding out their particular area of emphasis, courses in things Mines has taught for decades — metallurgy, mechanical engineering, or natural resources law.

Interested students have hailed from NASA, the European Space Agency, startups and established aerospace companies. They have included economists and lawyers seeking to understand the field with an eye toward shaping future policy, Abbud-Madrid said.

The program emphasizes those down-to-earth aspects of the field.

“Without understanding the economic costs and opportunities involved, none of this will happen,” he said. “Resources without the ability to use them are just elements.”

The center’s faculty predict precursor missions establishing the field are coming within a decade.

Companies such as Planetary Resources, based outside Seattle, and Deep Space Industries, in San Jose, California, have been working for several years and have investor backing to go after resources on asteroids or the moon.

Space mining a few years ago elicited excited talk of mining asteroids made of pure precious metals, but those discussions have given way to more basic and attainable goals, Abbud-Madrid says.

The resource likely to be sought first in space will be water, Abbud-Madrid says.

If you can collect water on the moon or an asteroid and break it down into hydrogen and oxygen, you’re mining the key ingredients to support deep-space exploration — hydrogen for fuel, oxygen for life support systems and water for human consumption.

Some of the earliest space resources missions will try to extract water and collect hydrogen for robotic refueling in orbits near the moon.

Being able to refuel a rocket in space — where, freed from the constraints of Earth’s gravity — missions could move more easily and cheaply.

Centennial-based ULA is designing an upper-stage rocket engine that’s capable of re-firing many times in orbit, meaning it could be re-used repeatedly for different missions in orbit or around the moon if it could be refueled.

Before he left ULA, Sowers led a study into what price the company would need in-orbit fuel to sustain such robotic missions. ULA publicly identified the price to give space entrepreneurs a sense of the volumes and costs involved to attract ULA as a customer for hydrogen mining systems.

Now at Mines, he’s seen engineering work on a system that, in theory, would be able to produce hydrogen from lunar “soil” at the price ULA needs. He’s hopeful a prototype will be built and tested in coming years.

Before those systems are launched, companies will need missions that identify precisely the nature and location of water that’s been detected in the moon’s polar soil.

That means the early pioneers of space miners are more likely to resemble yesterday’s prospectors than mine barons, Sowers predicted.

“In the old days, it was the guys with the picks and mules,” Sowers said. “In the modern day, it will be remote sensing and geophysical measurement. That’s where it will start.”

NASA studies lead scientists to believe hydrogen — likely in water — exists commonly in the permanently-shaded areas of the moon. Whether that water is in a tundra-like crust or in deposits of soft “dirty snow” isn’t known, which could change the designs of machines built to extract the water, said Dreyer.

Mining and energy industry officials connected to Colorado School of Mines’ more traditional disciplines have grown interested the space resources, too. A lot of expertise in mining and oil drilling may translate into opportunities in space, Abbud-Madrid said.

“The companies are watching what’s happening, and they’re waiting to see if this is for real,” he said. “As soon as they see that, they’ll be in.”

Student credit hours (Sept. 2016-May 2017)

| Rank | Prior Rank | Institution |

|---|---|---|

1 | 1 | University of Colorado Boulder |

2 | 2 | Colorado State University |

3 | 4 | University of Colorado Denver | Anschutz Medical Campus |