But, Seriously, Where Are the Aliens?

Humanity may be as few as 10 years away from discovering evidence of extraterrestrial life. Once we do, it will only deepen the mystery of where alien intelligence might be hiding.

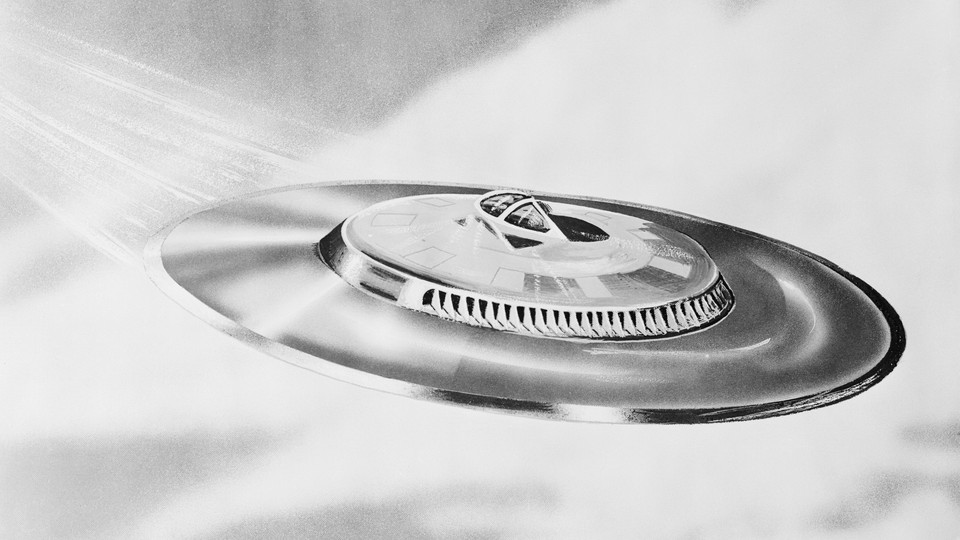

Enrico Fermi was an architect of the atomic bomb, a father of radioactivity research, and a Nobel Prize–winning scientist who contributed to breakthroughs in quantum mechanics and theoretical physics. But in the popular imagination, his name is most commonly associated with one simple, three-word question, originally meant as a throwaway joke to amuse a group of scientists discussing UFOs at the Los Alamos lab in 1950: Where is everybody?

Fermi wasn’t the first person to ask a variant of this question about alien intelligence. But he owns it. The query is known around the world as the Fermi paradox. It’s typically summarized like this: If the universe is unfathomably large, the probability of intelligent alien life seems almost certain. But since the universe is also 14 billion years old, it would seem to afford plenty of time for these beings to make themselves known to humanity. So, well, where is everybody?

In the seventh episode of Crazy/Genius, a new podcast from The Atlantic on tech, science, and culture, we put the question to several experts, including Ellen Stofan, the former chief scientist of NASA and current director of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum; Adam Frank, a writer and astrophysicist at the University of Rochester; Anders Sandberg, a scientist and futurist at the University of Oxford; and Tim Urban, the science essayist at Wait But Why.

Proposed solutions to Fermi’s Paradox fit into three broad categories.

One: They’re nowhere—and no-when. Aliens don’t exist, and they never have. This scenario might have seemed more likely in the universe imagined by Aristotle and Ptolemy—a small assortment of celestial orbs spinning around a singular Earth. But that isn’t the universe anybody lives in. After searching the skies for Earthlike planets for centuries, cosmologists have, in the last two decades, broken open the cosmic piñata. Today they estimate as many as 500 billion billion sunlike stars, with 100 billion billion Earthlike planets. The more we learn about the universe, the more absurd it would seem if all but one of those bodies were bereft of life. To my mind, this is both the least likely answer to Fermi’s Paradox and the only one that fits all the evidence currently available to astrophysicists.

Two: Life is out there—but intelligence isn’t. Ellen Stofan predicts that we’ll find evidence of simple life on Mars or a faraway moon within the next 10 to 30 years. But she’s imagining something more like microbes or algae, not underwater cities in the liquid-methane lakes of Titan. This shifts the question from “Where is everybody?” to a more sophisticated query: What precisely is keeping an infinitude of dumb molecules from assembling to form an abundance of intelligent life?

Think about all the factors that add up to the creation of a human. First the spark of life, followed by the creation of simple cells, then complex multicellular organisms, then the formation of organs like brains. If humanlike intelligence is rare, one of these steps must be quite insurmountable. For example, it’s notable that Earth has several million species of life, but only one has produced a civilization—that we know of. The relative silence of the universe suggests some kind of “Great Filter” that is restricting the creation of more intelligent beings. More ominously, some scientists think it’s possible that this Great Filter isn’t in our distant past, but rather in our future; so, it’s not that intelligent life is rare, but rather that it pops into existence for a few thousand years before getting wiped out of existence for mysterious reasons.

Three: Intelligent life is abundant—but quiet. This possibility, known as the zoo hypothesis, invites some of the strangest speculation. Maybe humanity is still so basic and primitive that advanced civilizations don’t think we’re worth talking to. Or maybe those other civilizations have learned that broadcasting their existence leads to extermination at the hands of violent, intergalactic colonizers. Or maybe our solar system just happens to be located in a quiet, exurban cul-de-sac of the universe, an accident of cosmic geography. But none of these theories hold a candle to my favorite conjecture of all: slumbering digital aliens. To understand why intelligent life might prefer to be based in a computer or cat-napping through the Anthropocene, check out the episode.