A Soda Company’s Long Obsession With Outer Space

A proposal for a space-based ad is only the latest iteration of Pepsi’s fascination with the skies.

Think about the dreaminess of twilight, when the sun has slipped below the horizon, and the darkening sky is streaked with dusky purples and blues. There, among the emerging stars and the silvery moon, lustrous as a pearl, you see it—an ad for a soda company.

This was the future envisioned by PepsiCo, specifically the corporation’s division in Russia. According to a recent story by Futurism’s Jon Christian, the branch planned to launch an “orbital billboard,” a cluster of small satellites flying in formation, like migratory birds that want to sell you something. The ad would orbit more than 250 miles above Earth, at about the same altitude as the International Space Station. In the early morning and evening, little sails on the satellites, made of reflective Mylar, would catch the light of the sun and become visible to the ground. The artificial constellation, blinking a logo, would promote Adrenaline Rush, a PepsiCo Russia energy drink aimed at gamers.

A Russian company has already tested a prototype using a helium balloon that carried one of its reflectors into the stratosphere, a layer of Earth’s atmosphere far below the edge of space, Futurism reported. But that’s apparently as far as this effort is going to get; this week, a PepsiCo spokesperson in the United States shot down the idea, saying there had been a miscommunication between Russian and American PepsiCo employees, perhaps because of a “language issue.”

No one has ever put a billboard of satellites like this into orbit. But companies have proposed advertising in space for decades, even on the surface of the moon. They want as many eyes on their ads as possible, and they’ll fill up blank spaces where they can find them, from the sides of skyscrapers to the in-flight maps on airplanes. What’s a better blank space than, well, space?

Pepsi’s obsession with decorating the skies actually goes back decades. The fascination began years before man or satellite left Earth, in the 1920s. Pilots started running paraffin oil through their planes’ exhaust pipes and zigzagging through the clouds, leaving fluffy trails of white smoke behind them. Skywriting, risky and mesmerizing, was “considered the future of advertising,” as Adrienne LaFrance wrote in The Atlantic in 2014. Companies lunged at it, Pepsi hardest of all. In 1940 alone, it paid for about 2,225 writings over 48 U.S. states, Mexico, Canada, Cuba, and South America, according to the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. The corporation became one of the longest-running contractors in the skywriting business.

Then NASA came along, and after a few missions to the moon, the agency started sending astronauts to space on the Space Shuttles in the early 1980s. The effort garnered tremendous media attention and public interest. Brands, naturally, wanted in. In 1984, Coca-Cola asked NASA to take a can of soda along on a shuttle flight. When Pepsi heard about it, it offered one of its cans, too.

The rival companies designed cans that would work in weightlessness, with special valves to dispense the soda. According to a New York Times story, the Coke can cost $250,000 to develop. The Pepsi can cost—are you ready?—$14 million, according to the company. The cans flew on the shuttle Challenger in 1985. NASA, a federal agency that has avoided advertising anything since its inception, stressed that it considered the cans an engineering demonstration, a test of beverage containers for future thirsty astronauts. Coca-Cola and Pepsi, as you might expect, treated the mission like a commercial.

A decade later, the makers of fizzy drinks were at it again. Coke sent another custom-made dispenser on a flight of the shuttle Endeavour in 1996. Pepsi went even bigger, with the help of another space agency. It paid for Russian cosmonauts to pose with a four-foot-tall replica of a Pepsi can while they conducted a spacewalk—a routine but dangerous procedure—outside the former Mir space station. The company refused to say exactly how much the stunt cost, but said it was in the seven figures.

Unlike their American counterparts, Russians don’t mind advertising opportunities, especially lucrative ones. Over the years, Russian astronauts have filmed commercials for Pizza Hut, RadioShack, and an Israeli brand of milk while in space. And the country has had a special relationship with Pepsi since the Sputnik days.

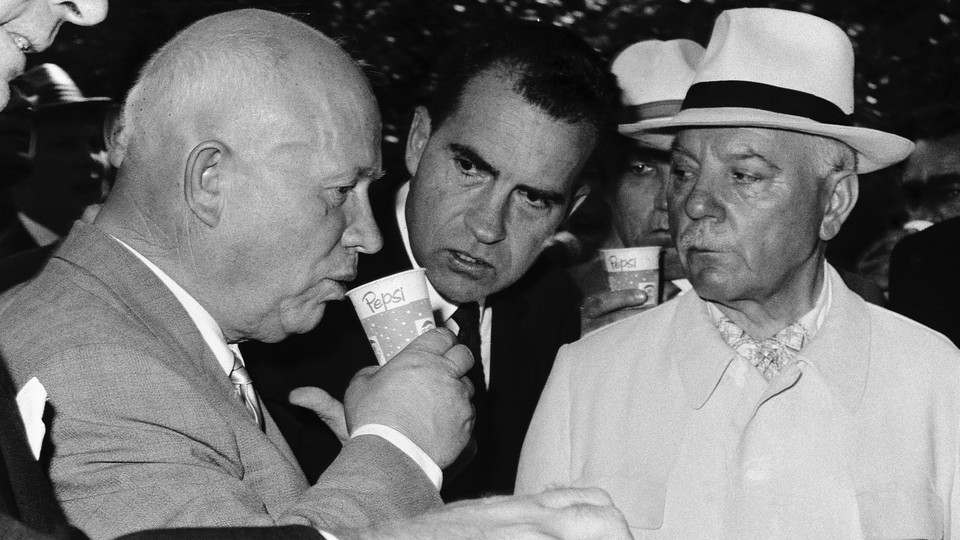

In 1959, the U.S. and the Soviet Union took turns showing off their culture and innovation to each other. The Soviets came to New York City, and the Americans to Moscow, where they put on display their best products and, by extension, their distinct ways of life. At the American exhibit, the chairman of Pepsi asked then–Vice President Richard Nixon to get the Soviet premier to have a sip.

He was eager to break into the Soviet market before a rival, Coca-Cola, did. The resulting moment—Nikita Khrushchev with a cup of Pepsi in his hand—was captured on camera and spread widely. “This was the best advertisement that a company could possibly want in the Soviet Union at that time,” writes Ksenia Zubacheva in Russia Beyond.

By the 1970s, Pepsi was funneling syrup into the Soviet Union to be diluted and bottled in newly built factories. The arrangement involved a rather unusual payment scheme. Zubacheva explains:

Soviet rubles could not be internationally exchanged because of Kremlin currency controls, which made it illegal not only to trade them internationally but also to take the currency abroad. Therefore, a barter deal was made whereby Pepsi concentrate was swapped for Stolichnaya vodka and the right for its distribution in the U.S.—liter per liter.

Pepsi has invested in operations in Russia since.

The corporation’s thirst for advertising in space has persisted, too, in Russia and beyond. In February, Pepsi shared a clip of a spacesuited figure, complete with the iconic shiny gold visor on the helmet, stretching against a pole. “Gotta stay loose,” a caption said.

Soda makers are known for advertising their beverage as something you can have any place you like—“anywhere in the world / no matter where you are,” according to the song Coca-Cola hired Mark Ronson and Katy B to produce in 2012. In a boat in the ocean, near a menacing shark? Obviously. In the Arctic, with a bunch of polar bears? Of course. In the midst of a tense standoff between Black Lives Matter protesters and police officers? Why not. By these measures, outer space fits the bill.

There is one catch: Soda sucks in space. Without the reliable tug of Earth’s gravity, gas bubbles don’t rise to the top and escape, crackling as they go. Astronauts end up consuming more gas than they would back home, which means they’ll need to burp more. When we drink and eat on Earth, gravity pulls the liquids and solids down to become digested, while gases float back up and flee our bodies as burps. In microgravity environments, like on the International Space Station and the now-retired Space Shuttles, everything floats together like, as Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield put it so colorfully, “chunky bubbles.” Burping doesn’t occur naturally. If it did, you’d “throw up into your mouth.”

Astronauts who have had Pepsi and Coke in space weren’t wowed. “Results were mixed, and NASA did not add either company’s product to the Shuttle food pantry,” the National Air and Space Museum reports about the 1985 test. The Coke can from 1996 “sputtered, leaked and failed to fill their zero-gravity drinking bags,” according to the Chicago Tribune.

No matter. Soda companies don’t need astronauts anymore. They have satellites, like the ones that PepsiCo Russia planned to use for its energy-drink campaign. Once big and clunky, satellites now come in small sizes that are cheaper to launch.

Brands don’t have to rely on national space agencies, either. The commercial space industry has flourished in the past decade, and firms can pay rocket companies to launch stuff for them—or use rockets of their own. U.S. law prohibits regulators from granting licenses for “obtrusive space advertising,” but officials have approved payloads that were just for show. Elon Musk launched a Tesla on a SpaceX rocket. A company called Rocket Lab launched a shiny spherical satellite called a Humanity Star to promote interest in the cosmos. An artist, with help from SpaceX, launched a reflective sculpture shaped like a diamond.

These payloads irritate some people, specifically astronomers and researchers who study the space around Earth, home to thousands of satellites, some operational and others defunct. The astronomers say the artificial objects could disrupt telescope observations. Orbit conservationists say they pollute an already crowded place.

“Most of us would not think it cute if I stuck a big flashing strobe-light on a polar bear, or emblazoned my company slogan across the perilous upper reaches of Everest,” Caleb Scharf, the director of the Columbia Astrobiology Center, wrote in a post on Scientific American last year. (This sentiment has been around since the days of skywriting, a practice The New York Times once called “celestial vandalism.”)

But flashy spheres, shiny sculptures—these are short-lived things. The low-Earth environment, where the space station and many satellites orbit, still has enough air particles to slow down moving objects. Satellites without engines and fuel can’t lift themselves higher into orbit and escape the drag. The Humanity Star, for example, succumbed to Earth’s gravity and plunged into the atmosphere two months after launch.

The Pepsi billboard would have met the same fate. Unlike one of the Pepsi cans from the 1980s, which sits in a collection inside the Smithsonian, the first floating ad in space would splinter into pieces and vaporize as it hurtled back toward Earth. The return, fiery and fast, might resemble a shimmering meteor shower from the ground. Given its history, Pepsi might try to advertise that, too.