The Most Overhyped Planet in the Galaxy

A long obsession with Mars makes all the other worlds seem a little neglected.

Paul Byrne loves Mars. He wrote his doctoral thesis and several research papers about the planet. Most of his graduate students study Mars. And yet, earlier this year, he posed this question on Twitter: “If you could end the pandemic by destroying one of the planets, which one would you choose and why would it be Mars?”

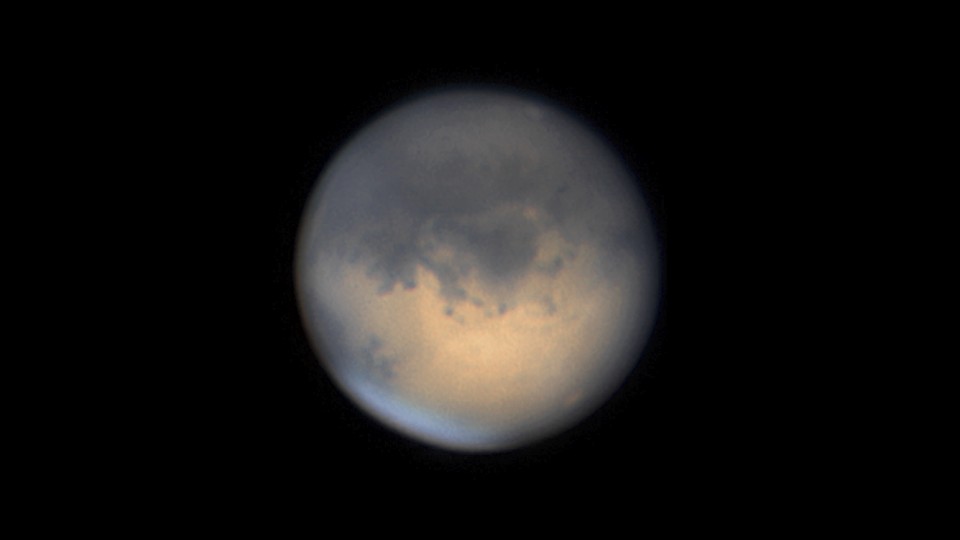

What does Byrne, a planetary scientist at North Carolina State University, have against the red planet? Nothing, he told me. But everyone else loves Mars too, and maybe a little too much.

Aside from Earth and the moon, humankind has studied Mars more than any other world in the universe. In the United States, many planetary scientists are devoted, in one way or another, to the study of Mars. Since 1996, NASA has sent more than a dozen robots to orbit, rove, dig, and hop around the planet. The latest NASA rover, Perseverance, departed for Mars in July, days after China and the United Arab Emirates launched their own missions to the planet.

The Mars monopoly is strong enough that it makes all the other worlds in the solar system seem a little neglected. Scientists are now preparing to negotiate top priorities for the future, a process that takes place once a decade. Mars won out in the previous round, leading to the Perseverance mission. This time, many scientists are rooting for a less Mars-centric outcome. The process, worked out over months in papers and panels, will consider a host of possibilities, all while reckoning with a fundamental question: Why explore any of these worlds at all?

Mars is marvelous—and there’s still a lot to learn about it: NASA’s fleet of rovers, designed to move at less than a mile an hour, has covered only a tiny piece of the planet, and to planetary scientists, there’s no such thing as too many data from another world. But several other worlds are worthy of attention, and they could yield surprises that Mars likely cannot.

While rovers have rendered Mars in stunning detail, capturing the fine texture of boulders and bedrock, spacecraft have experienced the outer planets as near-featureless orbs, their depths obscured in haze. Take, for example, Neptune and Uranus, which some scientists say stand a good chance of becoming top priorities in the upcoming negotiations. No spacecraft have visited these planets since the 1980s, and even those missions were onetime flybys. Launching Perseverance meant downsizing a mission to Europa, an icy moon of Jupiter, where life might swim in a subsurface ocean. An earlier Mars robot was chosen over a mission that would have dropped a boat on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, where the lakes are filled with liquid methane. The last time a spacecraft touched the surface of Titan was 2005, and its batteries lasted only a scant 72 minutes. (NASA approved a new mission to Titan last summer, but the spacecraft won’t reach the moon until 2034.)

“One of the really embarrassing things is that we don’t really know what the ice giants are made of,” Francis Nimmo, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz, told me. “Everybody calls them ice giants, but we don’t actually know that that’s true.” Ice is certainly one ingredient, Nimmo said, but beyond that, scientists can only guess.

The study of other planets seems like it wouldn’t have many implications for us earthlings, but making such predictions would be foolish, says Heidi Hammel, a planetary astronomer at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy. When scientists studied the atmosphere of Venus, a rocky planet, in the 1970s, they discovered that the presence of chemicals such as chlorofluorocarbons depletes the atmospheric ozone that absorbs harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun. “We used to willy-nilly just pump them into Earth’s atmosphere, because why not, until we realized—by looking at Venus—that these chlorofluorocarbons had a very direct implication for the ozone content in the atmosphere,” Hammel told me. In the ’90s, U.S. environmental agencies banned the use of these chemicals.

Venus might carry other lessons for Earth. It used to be a pleasant and hospitable place before its atmosphere swelled with enough heat-trapping gases that its water boiled away. Scientists don’t think climate change will push Earth to this brink, but Venus is a reminder that we shouldn’t take our planet’s atmosphere for granted.

Venus is hot enough to melt lead, and engineers haven’t yet perfected hardware that could withstand the planet’s scorching environment. Driving on Mars is a breeze in comparison, and rover missions there could be the key to discovering whether life has ever arisen somewhere else in the solar system. The surface of Mars hasn’t changed much in the few billion years since the planet lost its atmosphere and, with it, the watery conditions that would make life possible. The Perseverance rover, when it touches down on Mars in February, will search for signs of ancient microbial life preserved in rocky formations molded by long-gone lakes and rivers.

But to investigate whether life exists anywhere else in the solar system right now, Mars is probably the wrong place to look. In fact, the best candidates for this kind of search aren’t planets at all. They’re moons. There’s Jupiter’s Europa, and Saturn’s Enceladus, and Neptune’s Triton—all shiny, ice-covered worlds that probably harbor liquid oceans in their depths. And there’s Titan, the only spot in the solar system besides Earth where liquid rains down from clouds and fills lakes and streams on the surface.

These moons, however would take nearly a decade to reach. The journey to Mars takes a comparatively pleasant six months. And if the goal of exploring Mars is not just to learn more about Earth or search for alien life but to send people there someday, it makes perfect sense to deploy many robotic missions to scope out the place and test the technology. Other planets and moons are fascinating targets, with the potential to answer some of humankind’s oldest existential questions. But they are harder sells in the face of some of our most intriguing daydreams and ambitions: an outpost on the moon, or a community on Mars. A second home, or at least a place to plant a national flag before someone else does. People are partial to worlds with surfaces they can actually set foot on, and the ice giants have none.

Perhaps the most compelling argument for paying more attention to other worlds in the solar system, Mars or otherwise, is that they are the only ones we can conceivably visit. Astronomers have discovered thousands of exoplanets in the past quarter century, and they have begun studying some of them in detail, searching for indicators of life within the molecules of their atmospheres. But without the invention of warp drives straight out of Star Trek, we can’t put spacecraft around these other worlds. Reaching the nearest exoplanet would take tens of thousands of years. These days, scientists can acquire a similar level of detail for some exoplanets that earlier generations did with the planets of our solar system in the ’60s, but “we might never get beyond that,” Jonathan Fortney, a planetary scientist at UC Santa Cruz, told me.

Science fiction isn’t necessary to imagine what scientists and engineers could reasonably do in our own cosmic backyard, and in our lifetimes. They certainly would need bigger budgets and more political will from presidents and Congresses—and these decision makers usually would rather go to the moon or Mars. But imagine a boat on Titan that could sail the methane seas, smooth as glass. A spacecraft plunging through Venus’s sulfuric clouds, or circling Jupiter’s moon Io, the most volcanically active place in the solar system. A probe that peers into Uranus’s dense atmosphere, the color of pale turquoise, and examines its moons too. Did you even know that Uranus has moons? And that one of them is named Miranda? Mars isn’t our only neighbor in the solar system worth getting to know.